Lewis Owens on twelve meditations about the significance of the Bible at the end of the millennium

The twentieth century has been a predominately secular one, asserting its autonomy after the apparent “death of God”. Our present “post-modern” world disallows any all-embracing meta-narrative that stands outside of both the author’s intent and the reader’s interpretative capacity. The Bible has not escaped the deconstructive tools of literary criticism and hence can no longer categorically assert itself to be the pure, unfiltered “Word of God”.

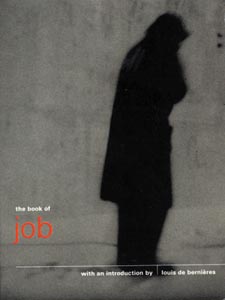

Instead, the manifest different interests and aims of the authors must be considered and respected. Nevertheless, both the Bible and the figure of Jesus still capture the imagination. Indeed, last year a series of twelve books of the Bible was published (Canongate Books, 1998 and due to be published in the USA in November 1999), with an introduction from a range of writers that, according to the publishers, “provides a personal interpretation of the text and explores its contemporary relevance”.

Upon reading these short introductions, one clearly gets the impression that, despite The Bible’s assertion that ‘there is something not quite right” about the “psychotic” Book of Revelation, there remains a healthy respect for the Bible as a literary work. For example, Doris Lessing claims to find in the Old Testament book of Ecclesiastes, “some of the most wonderful English prose ever written”.

Likewise, the writer and broadcaster Richard Holloway, in his introduction to the Gospel of Luke, suggests that a great work of art transcends linguistic imprisonment, providing a direct experience of unity between the subject and object. Great works of art, such as the Gospel of Luke, Holloway maintains, “create archetypes that express the general condition of humanity, and its sorrow and loss, heroism and betrayal”.

Furthermore, within the introductions to the New Testament books there is a desire to see in the figure of Jesus a person who can speak to us in our contemporary situation. Hence, in the introduction to the Gospel of Mark, Nick Cave stresses Christ’s isolation, aloneness and consequent humanity:

‘the Christ that emerges from Mark, trampling through the haphazard events of His life, had a ringing intensity that I could not resist. Christ spoke to me in his isolation, through the burden of his death, through His rage at the mundane, through His sorrow. Christ, it seemed to me, was the victim of humanity’s lack of imagination, was hammered to the cross with the nails of creative vapidity”.

This Christ is not the pure, meek, otherworldly Christ that the Church all-too-often offers, (despite the recent Easter poster campaign that had Jesus presented in the guise of the communist revolutionary Che Guevara advertising the words “Mild? Meek? As if! Come and meet the real Jesus”.) The Christ portrayed in Mark’s Gospel is a liberator, freeing us from our mundane, everyday existence pointing us towards self-liberation in an almost Nietzschean manner. “Christ understood that we as humans were for ever held to the ground by the pull of gravity our ordinariness, our mediocrity and it was through His example that He gave our imaginations the freedom to rise and fly. In short, to become Christ-like”. As with the Christ of Nikos Kazantzakis, we are called to overcome the temptation to live an ordinary, mediocre human life.

The emphasis on Christ as a self-liberator may also be seen in Blake Morrison’s introduction to John’s Gospel. This most poetic of gospels, rich in symbolism and metaphor, contains a self-confident and even argumentative Jesus. Morrison believes: “there is a ferocious existentialist ‘I am’ about him”. Once again, this is a Jesus speaking to us through his humanity and individuality, responding to the concrete situations with which he found himself confronted. By following the example of Jesus in this gospel, we are also called to passionately assert our individual honour and self-respect in the face of prevailing injustice. The key to the gospel, Morrison claims, is once again the emphasis on human freedom from internal imprisonment: “Some will take it as literal truth, and others embrace its imaginative truth. But there’s also what Jesus calls ‘the truth {that} shall make you free” (8:32). For John, this is what mattered most: the possibility that be reading his gospel we will in some way emotionally, aesthetically, intellectually, spiritually be liberated”.

Thus far, a Jesus who, through his very humanity, is able to cross the temporal impasse and offer insights into our contemporary human plight has confronted us. However, this stress on the universal human predicament is captured most poignantly not by Jesus but by the Old Testament figure of Job. As Louis de Bernieres claims in his introduction to the book: “Chapter 14 {of Job} stands independently as a moving lament for the human condition: ‘Man that is born of a woman is of few days, and full of trouble. He cometh forth like a flower, and is cut down’”.

These words are as sharp today as ever. In the present era of mass-destruction and heinous barbarism in which evil appears to sit proudly in the director’s chair, it verges on embarrassment, disrespect and even rudeness to speak of the “goodness and love of God” while the innocent suffer. Defending one’s individual self-respect and integrity today requires a rejection of passively and blindly accepted religious assumptions. We have a duty to question the existence not only of the benevolence of God, but of God’s very existence. We must shout and rebel until answers are forthcoming and if no answer is given, then perhaps is not our faith to be placed rather in the humanity that we can tangibly and constructively mould?

The figure of Job transcends the paralysing fear of God and asserts his own individuality and integrity epitomising, according to de Bernieres, “a classic existentialist hero”. Indeed, twentieth century religious existential thought has often evoked Job as its hero: the courageous one who dared to resist being used merely as a pawn on the Almighty chessboard.

As the millennium draws to a close, humanity today, like Job thousand of years ago, still laments that the ultimate question of God is as unfathomable as ever. De Bernieres concludes his introduction with this yearning in mind and the desired integrity and honour of the human individual: “He {God} has still failed to appear in court, and we construe His absence either as non-existence, hubris, apathy, or an admission of guilt. We miss Him, we would dearly like to see Him going to and fro in the earth and walking up and down in it, but we admire tyranny no longer, and we desire justice more than we are awed by vainglorious asseverations of magnificence”.

In our current situation of post-modernity and pluralism, we often find ourselves in an uncomfortably alienated situation of “homelessness”. There is no longer any one privileged ‘true” view of the world. The Christian no longer remains unchallenged when asserting that his or her world-view is “correct” and their opponent’s “false”. Indeed, any claim to have found a “home” always requires an open front door, lest a dialogue is prevented and a sterile dogmatism prevails.

Nevertheless, there are certain maps that may be consulted to aid one along the unending road. These maps do not necessarily lead to a secure home, but may enable one to avoid some of the manifold pitfalls that are littered along the way. Charles Johnson, in his introduction to the book of Proverbs, believes the book to be a map a stability to guide us through the tumultuously chaotic world. Stability is welcomed, however, only if it does not lead to stagnation and the refusal to travel any further along the road of self-discovery and self-liberation.

David Grossman, in his introduction to the book of Exodus, stresses how the story reflects the soul of the Jewish people, constituted by both the desire for wandering and searching, as well as the longing for a “place”. This perpetual and often allusive search for security, our Ithaca, is also an epidemic of the modern age. Nikos Kazantzakis claimed: “I battle on, but I don’t know if I will ever reach Ithaca. Unless the journey itself is Ithaca”.

The Bible does not necessary lead us to our personal Ithaca. However, as these introductions attest, it still retains a contemporary significance that can speak to us in our concrete human situation. The issues that are dealt with in the Bible are issues that still confront our scientifically dominated world today. Thus Stephen Rose, who refers to himself as an “ex-orthodox Jew, an atheist and a biologist” can highlight the similarities between the issues arising from the book of Genesis and those concerning both the human and physical sciences today.

Of course, it would be erroneous to conclude that science need only look to the Bible for the answers, but it stresses that an active dialogue between religion and science may offer a fruitful insight into the human condition and the quest for knowledge. The Bible still deserves respect as work of literary and spiritual inspiration and is still an invaluable participator within today’s increasingly all-too-secular dialogues. Jesus, as a human being who had the courage and strength of will to achieve what he saw to be his Divine mission, still reaches into those depths of spirit that secular scientific reductionism cannot satisfy.

Dostoevsky once remarked that if somebody proved to him that Christ was outside the truth, he would continue to embrace Christ rather than the truth. Although this irrational passion is largely alien to the predominately scientific Western world, there is an apparent strong undercurrent that yearns for spiritual fulfilment. These introductions to twelve differing Biblical books are testament to this contemporary existential and spiritual searching. However, as Kazantzakis once suggested, “perhaps ‘God’ is simply the search for God”.

“If you want happiness and peace of mind, believe; if you want truth, investigate.”

– Friedrich Nietzsche.