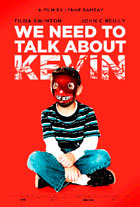

Reviewed by Declan Tan

Lynne Ramsay’s deranged adaptation of Lionel Shriver’s equally deranged novel (which Shriver quite garishly lauds on the film’s poster) is a decent stretch of film that concentrates more on the director’s ambition than it does on the novel’s. The result is a sometimes over-stylised but darkly entertaining genre-mix of gallows humour, psychological horror and suspense; likely to resonate more with shit-scared parents out on ‘date night’ than with their demonic kids, who have probably seen it all before, in more detail, and probably with gory special effects.

Tilda Swinton plays Eva, the mother of Kevin (Ezra Miller), a teenager imprisoned after murdering several students during a high school massacre. Switching back and forth in sequence, we’re shifted from post- to pre-rampage and back, as Eva visits Kevin, avoids humanity and generally tries to make sense of what happened, looking for the ‘Why’, and the reason for her continued estrangement from her husband, Franklin (John C. Reilly) and daughter, Celia (Ashley Gerasimovich).

Channelling Haneke for thematic matter at alternating moments, with echoes of Benny’s Video and 71 Fragments…, Ramsay manages a visually impressionistic swish every now and then, while intermittently falling flat by overpainting the image elsewhere. And, for all its heavy subject matter, Kevin plays a little light and airy. Which isn’t even a criticism.

It works as a reasonable horror flick of sorts, the kind that isn’t quite dumb enough for you to scoff at, but also not ‘new’ enough for you to still be discussing it by the time that once-a-week ‘date night’ draws to a close. There’s no groundbreaking exploration of ideas here; a re-treading of the line between nature and nurture while arguing for neither (though, perhaps, a mixture of the two), it begs of its audience the book’s dust-jacket praise of “intelligence” and “bravery”, merely by showing that every one of its characters abominates another in their own way, in an ever-developing culture of detachment and familial alienation.

Though Ramsay goes where Haneke didn’t, (i.e. the trite explanations of delusions of grandeur; the checklist of psychopathic behaviour; the roar of the crowd from the boy’s perspective; and Kevin’s commentary on television,) it’s when it tries on the big woolly jumper of social commentary that the film feels a little over-dressed, and at times the visuals match Ramsay’s overblown sense of impact and importance. Everything here but the dialogue seems to work, leading Kevin to overstep on occasion so rather than allowing its audience some interpretation by implication. It all gets a little too obvious. But there are successful moments in between, an example being Franklin’s advice to Eva that she “needs to talk to somebody” and get professional help, but that he is obviously unwilling to be the one to do it, a message that nods to the film’s increasingly ironic title.

Where the book was an example of an author creating an explainable context for their overwriting – Eva is herself a writer, it seems that Ramsay has gone for the same, silver screen style, with gaudy visuals that too frequently call attention to their cleverness. Further hindered by strained attempts at ironic music playing over an otherwise disturbing scene, the artistic and filmic references pile up a little too blatantly. Some other choices of music do, however, work well, and create a haunted idea of past and how it can never reached again fully, or for Eva, even partly. This demands that Swinton spend most of the film near-catatonic staring eyes through everything, while Reilly is wasted in a nothing part, a character without depth, a seeming requisite for a film like this; only one side sees, the other is ignorant/blind to the son’s behaviour (reminiscent of the also-competent Joshua and later Orphan).

In contrast to the cataleptic Eva, Kevin is a part an actor can go anywhere with, which, for the breaking-through Miller, means a heavy touch of the over-acting. So plenty twitching of the lips and shit-eating grins, while looking up menacingly from under your eyebrows, then.

But somewhere in here there is promise, if not intellectually, then at least as something reasonably pleasing to look at, as Ramsay’s certain (though loud) control of the camera looks to make a bigger sound in Hollywood and beyond. Let’s just hope for some meatier, less flowery, source material.