Chris Mitchell goes for lunch with Quentin Crisp

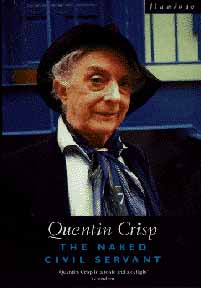

This month sees the publication of Resident Alien, the selected diaries of Quentin Crisp. It is difficult to surmise whether this man needs an introduction or not, such is his longevity as a cult figure of quintessential Englishness, “a stately old homo of England”, to quote one of his most famous phrases. Quentin Crisp is, after all, the man who first personified the concept of ‘camp’. “If I have a talent for anything,” he states, “it is not for doing but for being.” It was not until the 1960s, when he already over fifty years old, that Quentin first rose to fame with the TV adaptation of his autobiography, The Naked Civil Servant. In it, Quentin documented his early, life-changing decision that “instead of hiding my sexuality, I would announce it.”

With his henna’d hair, “gravity-defying” makeup and inch-long fingernails, the young Quentin Crisp cut a brave and audacious figure in 1930s London. Indeed, it is hard to imagine the outrage he must have provoked. As he notes in his book Manners From Heaven,

“During my Edwardian youth and Georgian middle-age the world (I mean Britain) stayed exactly where it was, aggressively conformist and conservative; I stayed exactly where I was, a blithe spirit revelling in androgynous anarchy, and there was a battle.”

This battle frequently became physical as well as psychological; Quentin’s accounts of the numerous attacks he endured on the streets of London lend a disturbing pathos to The Naked Civil Servant’s blend of pithy insight, amused self mockery and biting sarcasm. Indeed, the luminescence of Quentin’s prose soon won accolades which proclaimed him as a modern day Oscar Wilde, a comparison he has always refused. “When I was young, I thought Oscar Wilde was so noble. I thought he sacrificed everything for love. Then, when I became older, I realised this was complete nonsense. In the charnelhouses of London, Wilde only knew most of his lovers by Braille. It was utterly sordid.”

This battle frequently became physical as well as psychological; Quentin’s accounts of the numerous attacks he endured on the streets of London lend a disturbing pathos to The Naked Civil Servant’s blend of pithy insight, amused self mockery and biting sarcasm. Indeed, the luminescence of Quentin’s prose soon won accolades which proclaimed him as a modern day Oscar Wilde, a comparison he has always refused. “When I was young, I thought Oscar Wilde was so noble. I thought he sacrificed everything for love. Then, when I became older, I realised this was complete nonsense. In the charnelhouses of London, Wilde only knew most of his lovers by Braille. It was utterly sordid.”

Tired of England’s pernicious and parochial character, Quentin moved to New York in the early 1980s. By this time he was over seventy years old. After running various skirmishes with the US immigration authorities, Quentin succeeded in keeping his British passport and becoming a resident alien. “The English always say that the Americans are so false. But I don’t spend my time wondering if the man in the deli really wishes me to ‘have a nice day.’ If he didn’t, then he wouldn’t say it, surely.” Quentin warms to his theme. “In New York, everyone is your instant friend. If you were to stand up in this diner now and shout, ‘I’m putting on a cabaret’, then everyone would gather round and ask, ‘Where will it be?’, ‘What will it be about?’, ‘Who will you hire?’. If you did that in England, there would be absolute silence, everyone would stare into their soup and think, ‘How appallingly embarrassing.'”

Quentin is now the most interesting octogenarian on earth, enjoying “growing old disgracefully” as he puts it, with his purple rinsed hair and layers of foundation still firmly in evidence. “The problem with England is that everyone is convinced that you can’t make a living doing nothing. However, in this I feel I have succeeded to some degree.” Quentin’s New York existence is made up of socialising, film reviewing and various appearances in movies, TV and the theatre. “I live quite comfortably on publicity champagne and peanuts. The last time I went to a launch I took a friend. He immediately dived for the champagne and I had to say, ‘No, no! Act more like a star!'”

Quentin also entertains an endless stream of well-wishers from all over the world by the simple expedient of having his number listed in the New York phone directory. This leads to all manner of curious individuals contacting him. “A young lady once phoned me at seven in the morning and asked how she could make sure that didn’t smudge her lipstick. I said, ‘Don’t drink anything, don’t eat anything and certainly don’t kiss anything.’ You’d think she could have worked it out for herself.” Despite his avid socialising, Quentin refuses to buy an answerphone. “To me it would be pure science fiction.”

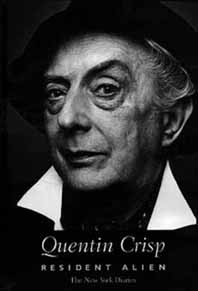

The only concession Quentin makes to his age is to spend two days a week “doing absolutely nothing” in his tiny bedsitting room on the Lower East Side. “I have to recharge my batteries. When you live in New York, as soon as you leave the house, you are under starter’s orders.” During these quiet moments, Quentin does crosswords – “they are the aerobics of the soul” – and, at the end of each month, writes his diary. Mentioning Resident Alien does not gain the normal authorial response concerning a new print baby: “Ah yes,” Quentin says, “I’ve just finished reading the proofs for that.” His eyes twinkle mischievously. “It’s absolute rubbish! They’ve taken out all of the dates, all of the places and all of the names for fear of causing offence.” He raises his eyes heavenward in mock resignation, knowing full well that it would be the most heinous breach of etiquette to say anything complimentary about his own new book.

Sadly, even with the publication of Resident Alien, the chances of Quentin returning to these shores are slim. “My agent asked me if I would be willing to go to England to promote the book. I have not refused, because I never say no, but I have said I will be extremely reluctant. I am too old for aeroplane travel. Whenever I arrive, they say, ‘Oh, you must be so tired.’ But I sleep the whole way on the plane. They seem to expect the excitement of flying to last the entire journey. What am I supposed to do for five hours, sit there saying, ‘Oh hooray! I’m in the air!” However, when I mention my home town of Brighton, Quentin fondly remarks of his time there at the Pavilion Theatre, shortly before moving to the States. “Brighton is very nice, but I’m not sure about the sea. I think the sea is a mistake. I mean, what does it want, banging and crashing away on the shore like that all day?”

The last time Quentin returned to the UK was a couple of years ago to play Queen Elizabeth the First in the film Orlando. “It’s the sort of film I wouldn’t watch myself in a hundred years.” Movies are much more to Quentin’s taste than books: “Books are for writing, not reading. But I am most definitely a fan of Mr. Tarantino. Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction are absolutely wonderful. The previous day he had seen Spike Lee’s new comedy flick, Girl 6. “It was a miserable film because of its subject matter. Who could find phone sex remotely interesting?” Quentin’s fascination with the silver screen recently led him to take part in a Calvin Klein advert. “I knew it was important because this enormous limousine purred up outside the house to collect me. It was so big inside that the first time it turned a corner I fell off the seat. We drove to a huge warehouse and I thought, ‘How fabulous! We’re going to remake The Charge Of The Light Brigade !’ But then we were told to stand on a piece of paper about twice the size of this table while a half-naked man writhed between our legs. I looked at Mr. Klein and I said, ‘But what does it all mean?’ And that was what they used in the advertisement…”

The last time Quentin returned to the UK was a couple of years ago to play Queen Elizabeth the First in the film Orlando. “It’s the sort of film I wouldn’t watch myself in a hundred years.” Movies are much more to Quentin’s taste than books: “Books are for writing, not reading. But I am most definitely a fan of Mr. Tarantino. Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction are absolutely wonderful. The previous day he had seen Spike Lee’s new comedy flick, Girl 6. “It was a miserable film because of its subject matter. Who could find phone sex remotely interesting?” Quentin’s fascination with the silver screen recently led him to take part in a Calvin Klein advert. “I knew it was important because this enormous limousine purred up outside the house to collect me. It was so big inside that the first time it turned a corner I fell off the seat. We drove to a huge warehouse and I thought, ‘How fabulous! We’re going to remake The Charge Of The Light Brigade !’ But then we were told to stand on a piece of paper about twice the size of this table while a half-naked man writhed between our legs. I looked at Mr. Klein and I said, ‘But what does it all mean?’ And that was what they used in the advertisement…”

The fabulous Quentin Crisp with

the equally fabulous Dr. Jake Eyers

Quentin has often asked himself the same question about gay militancy, a position which has caused him problems in the past. During a performance of his show An Evening With Quentin Crisp in California, Quentin relates how “several young men were very angry with me. When I asked why, they said, ‘You haven’t once directly asserted that you’re gay this evening.'” Quentin arches a neatly pencilled eyebrow. “You’d think to look at me would be enough. Obviously not. And that is why I do not march. I have realised I represent nothing grander than my own puny self. I am first and last an individual, not a spokesman for any group. I have lived my life with my sexuality clearly apparent. I cannot do any more.” The provocation of Quentin’s attire should not be underestimated, even in these supposed liberal times. With a mixture of incredulity and relish, Quentin relates a story from the Edinburgh festival several years ago: “A young man was performing a show where he impersonated me on stage, complete with clothes, make-up and accent. When he walked out into the street still dressed as myself, he was physically attacked!”

Thankfully Quentin’s days of being harassed on the street are long gone. He is a venerated celebrity on the Lower East Side. During our conversation, several people wave at him as they pass in the street, and a respectfully deferential young man who introduces himself as Winston comes in to ask Quentin for his autograph on a napkin. As I walk him back to his apartment, one of the bums hopefully shakes his cup and greets him with “Yo! Mr. Crispy!” We pause at the street corner to say goodbye, and Quentin leaves me with one last anecdote. “When I returned to the States after completing Orlando, I was stopped by the passport officer because of my status as a resident alien. He was an enormous man with a shaved head – he looked like an absolute thug. I thought, ‘Poor me, my time has come!’ And then the officer leaned over the barrier, pressed the passport back into my hand and whispered, ‘It must feel good to be so utterly vindicated.'” Quentin looks directly at me. “And it does.” With that, he gracefully takes his leave, his small figure soon disappearing amongst the busy sidewalks of the Lower East Side. Quentin Crisp – the definitive Englishman in New York.