This dialogue between Matthew Ritchie and Thyrza Nichols Goodeve first appeared in the catalogue for the artist’s exhibition Proposition Player, organized by Lynn M. Herbert, December 12, 2003-March 14, 2004, Contemporary Arts Museum Houston in association with Hatje Cantz Publications

Many thanks to Thyrza Nichols Goodeve for permission to republish

I always thought the best magic tricks were the ones you knew how they worked but, the trick was so perfect you still couldn’t help believing it. There are seven kinds of magic trick. the disappearance, the production, the transformation, the mentalist, demonstration, the anti-scientific demonstration, penetration, and the transportation. Now imagine if one trick did them all at once.

– Matthew Ritchie, 2003

As the story goes, I’d like to begin with a brief history of the project. How did it all begin?

As the story goes, I’d like to begin with a brief history of the project. How did it all begin?

In 1995, after many years of working as a building superintendent and not really making art, I got started again by making a list, and then the list turned into a map, and the map turned into a story, and then the story turned into a game. Since then I have typically worked episodically, through a series of site-specific projects that cumulatively described elements of a system or, more accurately, a way of working. I think this accumulation sometimes created the illusion of a progression, with a hierarchy of meaning. But it turns out that impression is even less than half the story. This show is a good time for me to evaluate the truth of that first impression and how closely it is related both to the true intentions of the work and to the physical forms it has taken on over time.

What was the initial list?

It was a list of everything I was interested in. It was grouped as forty-nine categories arranged in a grid of seven by seven, things like solitude, color, DNA, sex, everything I could think of. Each element on the list was represented in seven ways: as a scientific function, a theological function, a narrative function, a color, a form, a dynamic function, and finally through a personal, hidden meaning. But once they started crossing over from their little boxes, which happened immediately, that’s when it turned into a map, like a place, as if all the elements had become little cities one would like to visit. And then it became a story, almost automatically.

What was the function of the forty-nine characteristics? I mean, ultimately, what were you trying to get at?

The forty-nine characteristics were originally an attempt to simply represent the conditions of any system. Light, color, mass, space, time, etc. are aspects shared by painting with any cosmology or any representation of the universe. The many shows that followed were an exploration of the possibility of building consensus, or form, from contradictory narratives. Cape Canaveral and Morris Lapidus for Miami, the Brockton Holiday Inn and glacier climbing in Svalbard for the shows in [respectively] Boston and Oslo, the geological oddity of the Seven Cities for a show in São Paulo. Each show added physical details to the overall information architecture, trying to extend the idea of an open system to the physical form of the work.

The more I’ve looked at and thought about your work, the more it has become about manifesting structures of information and the information age, not just about painting. Or better, you’re using the medium of painting not to represent the issues and ideas of the information age but to translate them into another order, an order that is physical, where, as you put it, everything is there all at once.

I want to be able to see everything. It’s a fathomless desire, a weakness and a strength. But to do such a thing, you have to turn information into a physical form.

Which is so interesting because one of the most dramatic distinctions between the information age and the pre-information age is the increasing invisibility and non-physical form of things, like subway tokens becoming metro cards; coins and paper, credit, and ATMs; films into digital streams, etc.

Yes, so we need to make a visual metaphor for all the things we cannot see. I grew up with the information age. When I was in high school a digital watch was a rare trophy. Now a tidal wave of information engulfs us. They have just introduced a unit of measure that calculates planetary information flow. More information was exchanged in the last five years than in all human history. How do we deal with all this? How do we create a meaningful information environment? How can we learn to see information as form? I’ve always been interested in this idea of anthropomorphizing information and have wanted to use painting to prove one of the fundamental premises of information theory, that any sufficiently complex system will acquire its own internal meaning. Not only can you see all of it, but it can see all of you. I have also wanted to see if I could introduce certain fixed relationships into painting that would allow it to acquire the status of language. Then maybe this thing could talk back. I don’t know much about linguistics, but once I came across a list of the properties of language, and painting has all but one.

Which is?

Intertranslatability. It fascinated me that painting could be considered mute. In language the word “blue” can be translated into any language and will still always mean “blue”. But in painting there is no way to translate Picasso’s blue or El Greco’s blue from painting to painting. Pigments can’t be translated; they are specific, never general, never translatable.

In 1997, in an interview with Jennifer Berman for BOMB, you said, “… there are a lot of artists… who are doing work that I feel close to, and it evolves around ideas of treating art as language, and consequently inventing narratives, but not in some sixties way…” [Matthew Ritchie, quoted in interview by Jennifer Berman, BOMB Spring 1997, p.64.] Could you elaborate on that?

I guess what I was getting at is any discussion of my personal narrative must be closely linked to the personalized global practices that emerged in 1995-2000, where cosmologies and mythologies were a common tool for artists as divergent as Liam Gillick, Gregor Schneider, Manfred Pernice, Andrea Zittel, Kara Walker, and of course Matthew Barney and his Yale classmates Katy Schimert, Michael Grey, and Michael Rees. Shows generated by these artists and others often used complex titling and installation strategies like books, super-graphics, and implied narratives as part of their fundamental structure. The overall effect was a collection of closed worlds, a house of doors. I was very interested in the possibilities this opened up, and after the collapse of the master narratives in the eighties, it seemed inevitable that artists would turn to a self-contained practice again. Typical of these projects was an implication of a larger vision, which underlay any given project. My own project was established both to take advantage of that desire and simultaneously to counter it. I created narrative structures which manifested themselves as a nonhierarchical game space, a magic square, open to multiple contradictory readings and based on an open source material from subgenres commonly relegated to the backwaters of historical curiosity, such as Gnostic angelology, unified field theory, conspiracy theories of all stripes, creation debates, and evolutionary arguments – in short, every field where the desire for a universal taxonomy, a context outside all contexts, had outweighed truth, proof, or consensus. My project was hopefully a generous construction of arguments that was always intended to be impossible to be read as any kind of closed Wagnerian master myth and to be more a kind of open, porous toolkit for thinking.

Unlike Matthew Barney’s Cremaster cycle, which is often described as Wagnerian.

Barney was among the first artists of my generation who was not worried by his desire to include everything he wanted into his art. I had seen the work of [Robert] Rauschenberg, [Joseph] Beuys and [Sigmar] Polke and found them similarly freeing, but somehow that moment seemed lost to my generation. That was what I thought was so liberating about the early nineties: everyone seemed to say, “I’m interested in all this stuff and I’ll do it all at once, from Rikrit Tiravanija’s cooking to Andrea Zittel’s habitats. And that was fantastic. I was never attracted to this idea that art was somehow under siege or that preserving ideas of conservative technique was some kind of resistance. Nor did the myth of infinite progression seem particularly truthful either. I think something much more interesting has happened since then. An enormous space has opened up where we can see the possibility of these radicalized, spectacularized individual projects to change and evolve, to escape from the cultic and predictable obligations of art historical expectations. Instead of accepting a relationship to the Wagnerian model, which is based on the the model of traditional cult worship, I think we should be thinking about Milton, whose work was based on ideas of intellectual honesty, individual freedom, and responsibility. The ubiquity of cheap, low-res technology allows every artist to become their own NASA.

In other words, for me, the original idea that any sufficiently complex system would acquire its own internal meaning (information theory) has mutated into an omnivorous visualization system constantly generating multiple meanings. This system is not really being generated by me; it is a story by, for, and about everyone and everything. And so, without either falling or concluding as scheduled, my project has taken on an internal life. It has escaped. The separate characters have become highly individualized characters, places, landscapes, and organs, all competing and dreaming in an endless conceptual war consisting of endless victories for all. None of the work in the current show corresponds to the initial table of characteristics, colors, names, or functions. Instead the works all contain multiple and polluted variants and offspring of the original structure. One way to describe what I am doing is I am trying to describe and include what cannot be systematized. The classic regressions of [Bertrand] Russell’s set of all sets, or the Binding Problem, or the question of a priori consciousness, or the origin of source material for the Big Band, are all ultimately about asking what can and cannot be known. They are outside context questions.

What do you mean by “outside context questions”?

How can we perceive the structure that contains the model of our perception?

Do you think you have successfully given back to painting the idea of translatability? If so, isn’t it only within your system?

I think I have sort of, but the result has turned out to be a kind of conjuring trick with only one useful function: to show that all language requires an internal consistency, not only to function but to have integrity.

Does critique enter into your work? Is that even a relevant question? Or desire to get out of your work?

Could you expand on that a little?

About critique? What I mean by that?

Yeah.

The belief that art is less about creativity than it is about questioning art, society, power, money, master narratives. I came out of that tradition through academia and the Whitney program in the 1980s. But the more I got to know and write about art in the ‘90s after I left academia, the more narrow that view became, which is why Barney’s, yours, or Ellen Gallagher’s work became of such interest to me. In this more generative kind of work, critique is not the impetus so much as generating new systems. Creativity returns but through the lens of a very diffracted (post-Derridean / Haraway) space.

It’s an interesting question because the third thing I was interested in at the beginning of this project was the idea of the Ius Utendi, the model of law proposed by William of Ockham (one of the first proponents of intellectual freedom), which concerns the structures and questions that underly any self-critical, self-sustaining, open game of thought.

How has he appeared in your work?

Well Ockham is most famous for Ockham’s razor, a deductive mental tool.

Which is?

The simplest solution is the likeliest one. But determining the simplest solution requires an understanding of the entire context. In Ockham’s time, the simplest solution was to assume God was responsible for everything from wood floating on water to the motion of the planets. But that led to heresy because it conflicted with the idea of free will and to idiocy because the basic laws of observable science were constantly being challenged by this idea that they were “against the will of God”. It’s the same kind of thinking that opposes stem cell research today.

But Ockham is most interesting as an example of the power and limits of logical thinking – what you could call critique. He single-handedly challenged the rights and limits of the papacy at a time when it was the unchallenged arbiter not only of the present, but of the spiritual future of every Christian. He won through the force of logic on what he called the “right to use”, the belief that each of us has both rights and responsibilities that no larger structure can mediate for us. In short, he presents the individual as a moral ecology. Real critique must begin with an understanding of the entire system and one’s personal relationship to it.

Okay, so now I’ll come in from that other side. Your generation’s reliance on baroque internal myths, or even baroque public myths (science) in your case, has been interpreted as this kind of irresponsible system, because you could be interpreted as saying, “Well, everything is meaningful and everywhere, and it can go anywhere”. If that’s the case, then nothing means anything, and everything’s up for grabs, and it’s that awful postmodernism stuff, right?

Well, science is hardly a myth and like any truly complex system, it demands internal integrity. But I usually get asked the opposite question instead.

Which is?

“Why do we even have to know what it means?” I’ve heard that thousands of times. Most people don’t want to know that there’s an internal architecture, or background information, and that it all holds together.

That’s so depressing. Why can’t people understand that this is what makes the art so interesting. Certainly it’s what is strong and breathtaking about yours and Barney’s.

The criticism of the complexity is based on this unfortunate idea that we in the visual arts should be afraid to make big, beautiful, complex things in case we somehow “alienate” a frightened and timid potential audience. I do not underestimate the audience in that way. It’s so odd. The same people that worry about contemporary art in this way are completely unafraid of the Sistine Chapel, or The Matrix, or jet planes, which are much more complicated. Part of the premise of this show was the idea of shared and lost information, so to make the heads for The Fine Constant, I worked with ten-year-olds in Houston and New York, and they were not alienated by the complexity; they embraced it. They were less confused than anyone I worked with. So I think any audience can and will rise to the challenge of complex work as long as they feel they can trust the artist’s integrity. This is the most important thing, because only an internal integrity can guarantee an implicit order than transcends these kinds of questions.

That’s excellent.

There are also big differences between the various types of work that suffer from the criticism of complexity or hermeticism. You are the Barney scholar here, but it seems to me his work is based on the idea of constructing a mythology that builds upon itself. He’s forcing a kind of concentration on the viewer. Someone like Beuys was interested in placing himself at the center of a postwar absence, and his meaningful system was a conduit with himself as the social lubricant. Kara Walker, on the other hand, seems to be more interested in an epic David Lean-like portrayal that focuses less on one individual than on articulating the giant voice of moral betrayal. Whereas what I’m interested in is an opening up of consciousness, a reversion, a reversal, so that what happens to viewers is they think about things from the outside through the context. Information becomes the material, the form. So I see the paintings and all the things that I’m making as parts of something like a telescope. I’m trying to create a class of objects whose main property is that they turn the viewer’s consciousness back out. All the information in my work can be found in the public realm, on the internet or in any public library, but what I try to deliver is the idea of personal intellectual freedom, the right to think any thought on any scale.

In previous interviews you talk about how important it is that the systems you are exploring are real, i.e., part of the public or social order. The abstract, self-made, total fantasy system of the Cremaster is your exact opposite. You start with the rules in the universe that determine us as a game and watch the story grow.

Yes, we are all an expression of the game. We are part of a particular spread of cards, and those cards are going to be reshuffled tomorrow and the day after. This is the hand you’ve been dealt, so it’s up to you to make a story out of the random insane collection of things that are happening to you right now.

It seems like your story of life has an awful lot to do with rules, doesn’t it? Would you say, for you, rules are almost the primary material?

Wow, that’s a really rich question. Especially since a good part of my life was about circumventing rules. [Laughing.] And I’d really like them to answer it for you. [Ritchie hands her “The Rules of the Game”.]

Are you kidding?

No. You are right – the relationship between the rules and the information, between signal and noise, is the question. It’s the question for everything. Not just for art making, but life. Life is about rules. You can say you “don’t want to learn”, but you have to learn about gravity. You have to learn about food and water, and then you have to learn about social life to keep getting food and water. The rules that we tend to think are the most important end up being, in the larger picture, nothing compared to the fundamental rules in your own life. Like when you will die. The whole point about rules is that they are what allow you to play the game. But just because you know the rules doesn’t mean the game is any more predictable, or any less fun, or any less absorbing. You know you’re going to win and lose, and that’s what counts.

Most rules aren’t about learning, just obeying. One doesn’t have to understand or even know about gravity, but one does have to obey it.

Yeah, that is certainly what we have been told. But who told you that, and why? The new show is very much about this. Like, in the end, is a story really more about its rules? Is it all about the setup? Or can we look at all the rules at once?

Of any one moment in time, a person – or anything? Why is that important? What does one get by seeing all the rules at once?

Everything. All those rules are conspiring in a nonhierarchical space, where everything is potentially observable at the same time. Maybe the rules are just another way of asking what will happen next?

Which is the fundamental structure or definition or narrative. But what you are talking about is more about breaking through all the dimensions and seeing everything at once. Maybe it’s the word “rules” that throws me. Is there another word for what you’re talking about?

Yes, there are lots because I don’t even think what I’m interested in is about “rules” in the narrow sense. I’m really looking at the fundamental properties in nature (that are sometimes called constants) that underlie everything. Laws tend to express the relationships of constants. But the other thing that’s specifically interesting to me, in terms of what you’re asking about, is that every individual person is building his or her own information mass, and although each mass is derived from the laws underlying most of the universe, everybody becomes their own set of dice – or their own pack of cards. We are all making our own rules – in defiance of the underlying ones.

The difference between the pre-information age and post is precisely this issue of pen access to “all” knowledge. We suffer from what William Gibson calls “information sickness”. Survival, of the fittest is no longer who is the one who knows everything, because everybody can do that to some extent via the internet and technology. But power or success or achievement or breakthrough comes form the ingenuity in how one makes sense of the information. In your model, it is what roll of the dice or division of cards each person develops.

Yes, when you have a new experience, the hippocampus actually rebuilds itself. Information, new information, literally makes the brain change shape. They’ve been doing these studies recently with monks that show the alpha brain waves calm down during meditation. The hippocampus actually changes shape. Buddhist monks and people who don’t meditate have brains that actually work differently. It’s actually a physical change. So every day we’re making a map of our life in our brain. We’re doing what we’re talking about in a very abstract way, processing everything into a physical object, inside our heads, every day.

So one can look at your work as much as a kind of map of the brain, and not just the idea of the universe and the cosmos? You put it beautifully in 1997 in the Jennifer Berman interview: “… you’ve got hundreds of competing impulses – your skin is itching, you’re responding to pressures and thoughts of your age, your body is deteriorating, you’re going to the gym. It’s a mess. This temple of activity. This hive. The heart’s beating, you can hear it ticking in the back of your mind. And your brain, god knows what’s going on in there. No one’s even close to figuring that out. And so this is an attempt to try and map what it is like to be a person”.

Yeah.

Have you ever experienced the sense of your brain growing?

Oh, God, yeah! And not just taking drugs. If you pay attention, you can feel it all the time.

But isn’t that amazing? I remember the point when I felt my brain matter growing. There was this feeling, literally, of more stuff going in and growing, and I could understand things I couldn’t before.

Yeah, that’s amazing. And then the real trick is you’ve got to figure out a shape for it all. Like will the form the information takes become a useful tool – like a personal cosmology – or more important, can you make it into something you can use or at least tolerate?

Tolerate is an interesting word. It’s about finding a level we can tolerate in the sense of a threshold we make, manage, and use. Otherwise information saturation becomes painful, and as Gibson says, we get sick. Is that what your paintings do? Are they ways of tolerating information overload?

I think so. Raw information has the ability to cause real disorientation. Information has to be cooked. The paintings are a kind of immune system; literally pictures of thinking.

Like what hydrogen actually looks like if it turns into knowledge?

Yes.

And yet, color and line are your vocabulary. Color’s the most important element, in a way, right? Are there specific associations with each color?

Well, originally there were seven colors with very specific hues that were in fact directly related to certain ideas I had about color theory. But then as they started to bleed and cross-mingle and procreate with each other, it was like all these children emerged. Children in the form of really dirty colors. But in truth, I would say that formally the paintings rely as much on the idea of “fill” as they do in color.

Territories.

Yes, in a way this goes back to the map and to the problem of how to contain or shape information. There’s actually a mechanical model of how much information one can contain in a space, based on the number of colors and how dense they are. It’s why maps look the way they do. They’re not brightly colored all over because, if so, you wouldn’t be able to look at and read them anymore. So when I was figuring out how to make these paintings, I had all these books on color. There was this book called Envisioning Information, which is very famous. It is all about how to make good and bad models for presenting information.

And yours, are they good or bad models?

I think mine are terrible models. [Laughter.]

Now why is that? Why would that be more compelling for you than doing “good” models?

Well, a “good” model for information is one where it’s totally legible to any person, for instance, a train schedule. Such models shouldn’t be confusing but completely ordered.

So, good models for presenting information are by definition not very interesting art. If so, where does your work stand? Or why work within these boundaries, which seem to contradict one another? What I’m getting at is, you seem caught between representing or modelling information via painting and making art. Art and information seem to be totally at odds, and yet those are the two things you are working with!

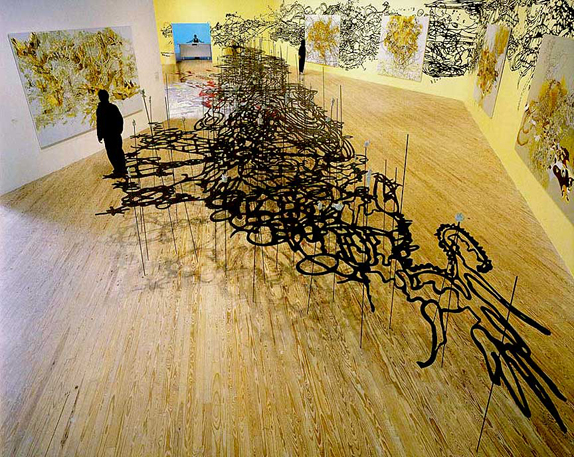

Well, a train schedule is very limited – its presentation of order relies on the absence of all other information. The real world is also a terrible model for presenting important information since it includes everything. But this project, as it stands in the Houston show, represents a kind of crisis, climax, or collapse of the earlier way of working precisely because of this conflict. For me this is an attempt to take advantage of the energy released as the first wave generated in 1995 comes crashing down. From this conflict, an alternate ecology, an ecology of information, has emerged, casting spaces against time, matter, energy. This ecology, rather than the initial rules, has emerged from inside the whole project. Rather than an episodic recapitulation of previous stories and structures, this show seeks to collapse all the categories, characters, and stories into one moment – a moment where the viewer can enter and begin to play the game him or herself. This entire show was also built around the idea of participation from the very beginning, not only from the side of the viewer, but also from the side of the maker. I wanted to explore how information as a material could be scaled and worked with by different kinds of collaborators using different technologies. I wanted to see how much could be lost and then regained as I scaled the different elements. So I worked with a totally diverse team of collaborators around the country who were each making a component, like the programmer making the game in California, or mold makers casting dice from prehistoric elk bones at the American Museum of Natural History, or ten-year-old children making the heads in Houston from Sculpy, or the water-jet cutter putting the sculpture together in his barn. I wanted part of the process to be about breaking this system of mine into parts and surrendering it to chance in the hands of others. This way the idea of a scalable language could really be tested out in practice. And their independent decisions ended up directly influencing the paintings and drawings, returning me to this idea of an endlessly opening, collapsing and infinitely generous structure. In terms of the viewers’ experience too, I have made it participatory. For instance, there is an interactive digital craps game, and there’s this pack of cards that I’m making. It’s a pack of all the characters, the forty-nine characters. So everyone who comes can play the game. [Ritchie pulls out a pack of cards.]

You have the pack of fifty-two most wanted Iraqi cards. Wait, this is your color – these are your colors?!

No, these are the US government colors.

Give me a break!

Funny, that is. [Laughs.]

So, you did dodge the question about the meaning of your color scheme, because there is a kind of army green throughout your world of color.

No, it’s just coincidence.

It’s just a coincidence?

People use these colors because they’re heavy on white. They’re cheap.

Okay, so talk about your craps game and cards. How do they function in the show?

You come into the show and are given a playing card with a character on it. But the show is not about all the characters. It’s not like they’re all over the walls or anything. There are also four suits in a pack of cards. So, now you’ve got forty-nine characters, and they’re divided into seven families each, and then they’re divided into four suits, which splits them up into their functionality. And the four suits represent the basic forces of the universe. (Which, by the way, were never included in the original seven families or the basic characters or properties, because I didn’t know enough to include them. Thank goodness.) So now, literally, these characters build the stories, but the stories are only a superstructure placed on top of the underlying structure, which is these four basic forces of the universe, and they then build through the craps game into a central figure, “the swimmer,” that ties everything together.

You mean these forces are undeniable?

We describe the universe through four forces that make up everything. The Weak Force, which is radiation, the Strong Force, which holds atoms together, Gravity, which holds the universe together, and Electromagnetism – most commonly understood as light.

Is that four because there are only four? Or have you chosen just four?

No, I hardly ever need to make anything up. There really are four forces that combine to make everything, including the four constants represented here: e = the elementary charge, c = the speed of light, G = the constant of gravity, and h = the constant of actio. For this book we made those letters each of of the four colors.

So according to Big Science, there are four?

You’re having a hard time with this aren’t you. Well, the theory is that they were all once one force – before the Big Bang, but there are lots more fours, just as there were lots of sevens when I needed them. You know, four seasons, four directions of the compass, four suits of cards. They’re all actually dependent on each other. The four forces also generate the four fixed units of measurement. So they’re all completely contingent on each other.

So, how does all of this work in your show?

The viewer walks in, gets one of these cards and then gives it to a guy at the gaming table. He then gives them the digital dice, which are four-sided dice cast from prehistoric animal bones, and then they play the digital craps game. And as they play the game they build the paintings.

Literally? During the show? How does that happen? Where’s “the painter”, meaning you? And why are the dice prehistoric animal bones?

The first dice ever used were astragals – ankle bones of a cloven hoofed animal. They are four-sided and were what were first used as dice, so in this case they’re cast from prehistoric giant elk ankle bones. They have four sides. One dice has four numbers and one has the four symbols of the suits: spades, clubs, hearts, diamonds – and they’re colored. Blue is spades, green is clubs, and so on.

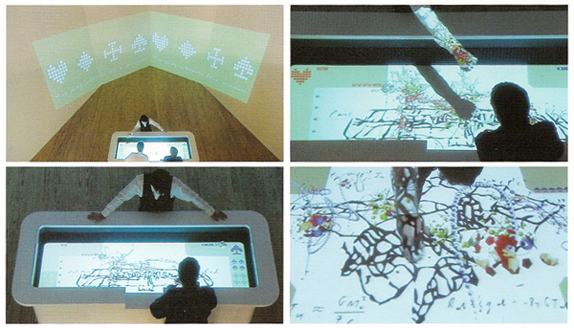

I also made a one-person craps table that serves as a projection surface. You throw the dice onto the table and they have tiny computers inside them that register what you throw and send a radio signal to a computer above. The computer then builds and projects random animated elements from a digital game onto the surface of the table, depending on your score. The evolution of the game resembles the main sequence of the paintings. Another version of the game, based on the same dice throw but using the random quality of the game to build a different image, is being projected on the wall as you play.

The game has five levels, because it’s also based on the voodoo universe, which has five levels and because voodoo is the only chance-based religion that I could come across.

This is all sounding like mad associative ranting.

And yet this is how I think. In voodoo you pray to a certain kind of god, but you might get another god coming in and at you. It’s also the only one where the universe invests itself in you, rather than you having to pray to it; it’s an inverted religion. And it’s sort of related to Christianity, which is something that I think is a legitimate context for me, if you do all these strange things in the gaming room, alternate versions of the structures of the paintings will build themselves in front of you each time.

How does one win?

Winning has to do with acquiring enough light and gravity and mass to get to the next level. It’s really just about play.

What if the first person who comes in ends up playing the whole time the show’s up?

Well, that’s great! But there is an end to it. Proposition Player goes through five stages, evolving from the first diagram, which is the underlying structure of the universe, to a painting, which is the evolution of atoms, and then, at the end, a figure emerges out of all of them, built out of the same parts.

Is there another metaphor besides “game” that works for you?

I think “life” is a good metaphor. [Laughs.] Or going back to the word I used before: “context”. Because all rules are interdependent on each other, they build a context. Light is dependent on nuclear fusion, which is dependent on the space / time structure of the universe, which is dependent on gravity. In other words, everything is linked together in a chain, in a context, which is the game. The game is much more than just the rules of the game. It’s the whole thing. If you talk out one part, one rule, the whole game collapses. So if that happens, how do you represent the context?

Like an organism. Is context another name for history?

The real context is the structure that contains the model of our perception that we think is the context – it is the framework that allows the rules of the game to be rule. So, how do you step outside a context that includes everything? This is the thing that I’m always talking about. it is the defining problem: context as theory. How do you represent the presence of the defining absence?

Defining absence, there’s a great definition of God. In a way for you to talk about history is off the mark because history, as a system for making sense of events of experience, is really just another kind of perception?

We can only see 5% of the universe. We’ve called another 25% “dark energy” and the remaining 70% “dark matter”. We’re working from a model with 95% of the information missing – so no wonder everybody’s acting like they’re in the dark. So the big question for me is: how do you visually represent that absence?

In The Fine Constant, each of the heads is based on a sculpture made by a ten-year-old in Houston who participated in a workshop based on my stories. The heads were decimated by a computer: we scanned the original head, turned it into polygons and reduced the polygons by 95%. This whole fabrication process was intended to represent the radical and persistent information loss that characterizes human experience and to show how in a way, it doesn’t matter.

Yikes!

And despite the fact that these heads derive from a story told to a child, who made a sculpture of the story that was then reduced by 95% in detail and then cast – we still have enough to understand it as a head! So the universe is still legible. It’s still working for you, even when you can only see 5% of what is there. But truthfully, as human beings, we can probably only even grasp about 5% of that visible universe. So we discard another 95% and make our daily decisions based on 5% of the available information we have left and yet we still feel the rightness of it all. Even though we’re only able to see only one quarter of one percent, we still feel we are connected to the underlying order. We can go further and further down in resolution, but as long as the underlying grain remains true, we can be convinced we are connected to the whole – we can ignore the overwhelming absence.

Sounds like the Bush administration.

But it’s how all of our information is produced. It’s like, how can you think about your own consciousness from outside your brain? I was making yet more Sculpy heads at a charity event and another ten-year-old came up to me during the workshop and said, “I want to make a model of the universe.” And I though, “Did someone send you to me? Is this a setup? You know, Candid Camera?” And then she said, “No, okay, the universe is too big. Let’s make the solar system.” And I was like, “Okay – phew!” And then she said, “But what does the universe look like anyway?” And all I could say was, “Good question.” I mean, isn’t that it? There she was, age ten, standing outside the universe going, “And so, what does this look like? How can I put it altogether all at once?”

And to her it wasn’t a game.

No, to her it was just like, life.