A call to arms (and mind) by Jonathan Reynolds

Theodor W. Adorno

A Theme Park; Consciousness; and the Reasonable Pessimism of the Frankfurt School

What certainly a consensus in social scientific circles has isolated and denominated as “capitalism” and “neoliberal democracy” has triumphed on the world stage. Many people seem to take this triumph as much for granted as they take the god, Jesus Christ, for granted, a god who, in contrast to the historically and textually understood Jesus of the Synoptic Gospels, approves wholeheartedly of private property or even the limitless accumulation of personal wealth, and signs off on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; His televangelist representatives advocate the sniper assassination of foreign leaders. (1) If, generally speaking, we believe our polls and demographics statisticians, there are a great many such non-pacifist Christian capitalists today in America. It seems likely even that a large majority of all Americans – and big percentages, if not large majorities, of Europeans, perhaps, also – believe not necessarily what the American Christian right believes but certainly would admit to believing that the “West is best” – that History and the evolution of civilization is on the side of Europe and America for good and sound reasons: “free enterprise” and a “free” or “democratic” society in which opportunity for wealth and happiness is within reach, in theory, to anyone.

If one is not of that group or demographic it may be necessary to conclude either that something has happened to our general consciousness that permits pretty farfetched or extreme inconsistencies or internal contradictions or that some kind of general cognitive remove has occurred by which consciousness is about to collapse as an attribute that distinguishes us from beasts. It certainly no longer seems safe to assume that “consciousness” is a word or concept that continues to have a straightforward meaning with positive implications. Things are crazy, and even the middle classes are getting hit so hard they are beginning to think that things just do not add up for them any longer. Just maybe, anyway.

What doesn’t add up?: contradictions so stark that what social critics of all stripe have referred to as “the system” – the status quo – seems actually to be in jeopardy. In the Middle East, governments are falling or have fallen in countries long supporting the pax americana, for example, Egypt. In the U.S., public services are being cut so much that police departments are laying off half their cops. The “greatest health care system in the world” still is one only the richest people can afford. But the thick veil of patriotism in America, the jingoism that has always touted the “free market,” still drapes over Lloyd Blankfein’s Wall Street. Republicans won the 2010 mid-term elections. Consciousness still is a vicious battlefield. The stakes apparently are extremely high. The business profits of the undoubtedly Christian-staffed Fox News (2) – still staggeringly great – are testimony that what certain thinkers, including followers of Marx, and, in general, adherents to what is called continental philosophy (some names here you may or may not recognize: Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche, Husserl, Sartre, Heidegger) would call “bad-faith consciousness,” is still rampantly at large. (Now, consciousness, bad or not, is one thing. What seems worse is the imminent bad fate of our civilization and, from the standpoint of an ecology that humans prefer, of the planet, itself. (3) Hmm… Bad faith, bad fate: it almost rhymes… )

These lefties decrying “bad faith consciousness” condemn and bemoan this. Others wonder how anyone, Marxist or not, can speak of “Late Capitalism” – as Marxists do – as if capitalism were ending or as if there was an end in sight to it.

That there is a problem, it seems that it is a problem, therefore, that has to do with “consciousness”: what people think and believe to be true, or to be right … what they see as reality or what should be reality. Many Americans, probably many Brits and other Europeans, even those only very mildly left-thinking in their politics, for some time now have been muttering sadly and angrily about ignorance or a lack of awareness. A new and greater awareness and understanding is lacking, they say, and if such an expansion of consciousness miraculously were to come about, everything would be a hell of a lot better. It might even be possible that the world wouldn’t end so soon. (4) Speaking just for myself, though I suspect it may be true of others, as well, this is particularly of interest because of a sense in my normal waking life of beleaguerment, frustration with contradiction, and oppression, both material and ideological.

Quite interestingly, what until recently, and for what still is the case for fans of Fox News, has been the rosy picture of Western, “Judaeo-Christian” civilization, certainly from the Enlightenment on, is identified – square in the headlights – as problematic by what was semi-panned by an otherwise sympathetic philosopher named Paul Ricoeur, as “the school of suspicion.” This goes back to the playful fire of the eminences grises of philosophy many decades ago, speaking about, among others, a small group of intellectuals known as the Frankfurt School of Critical Sociology.

These writers, whose frail existence flickered to life in pre-World War Two Germany, and who, improbably, despite their paler fire, ghostly fire, one might say, critiquing the much vaunted and completely taken-for-granted achievements of Western civilization, the received wisdom of the Enlightenment, itself, for example, survived (mostly) the Holocaust (most were Jews), survived the war, survived neglect by their brethren social thinkers, and now find themselves, posthumously (except for one, Jurgen Habermas), absolutely suitable for revisitation in 2011 for the insights their work has for us and our seemingly quite broken consciousness/es. (Informed readers of Spike undoubtedly will write in that they know all about the Frankfurt School, and always did: God bless these readers! I am only suggesting that the wider public – everybody! – should study these Prophets Ahead of Their Time – the Marxist thinkers of the Frankfurt School, about whom this present effort is concerned to expound.)

I am a Yankee. A gringo. So I can only speak for Americans.

If the problem is consciousness – or the lack of it – or it is “bad faith consciousness” vs good or “authentic” consciousness, consciousnesses struggling to become aware in order to act in better faith in these problematical times – this does seem to be particularly the problem in America, today, as Americans of different political stripe albeit for different reasons will assert. Accordingly, I suggest it would, indeed, be salutary to recall the works of social theory and critique produced by the Frankfurt School, a.k.a., the Frankfurt School of Social Research (here abbreviated “FS”), that was active from the 1930’s on, first at the University of Frankfurt, in Germany and, later, in diaspora, from various points around the globe. For consciousness, a knotty subject considered in many different arenas and aspects of life, is what the FS fundamentally addressed.

So what was the FS, and who were its charter members, these chartered thinkers?

By those who know a bit of the story already, the FS particularly is remembered – gone but not forgotten? – for a number of trenchant and highly original treatises of social and cultural theory and critique. (That they have been relegated to the past as anachronisms, even by the sensitive and sensibly engaged intelligentsia, is hammered home by the fact that a contributor to the famously reasonable, usually somewhat left-leaning, New York Review of Books, described recently in kindly if dismissive terms arguably the most important work by FS thinkers, Horkheimer and Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment, as “that neo-Marxist cult classic…” (5) Cult or no, as the degree of importance of the topic rises, so does the difficulty of explication – the “unpacking” – increase. Accordingly, I am faced with the problem of how to reach or speak meaningfully to those for whom Marx, historical process, the dialectic, the materialist conception of history, and the book called, Capital, in general, continue to be not merely unpalatable in a fast-food world but entirely removed from the general consciousness out there now that is in significant fashion constructed and fed by the likes of Rupert Murdoch.

Who were they? Self-identified as Marxists one of the motivating factors for their work, collectively, was to ensure the survival of the work of Karl Marx. And one reason for the neglect of the FS’s thinkers and theorists was their allegiance to Marx. Remember McCarthyism? Even if you do, you may not be sufficiently susceptible to remembering that great gray ozone haze of the Cold War, when there was a nuclear arms race, and if “communists” were mentioned at all, it was commonly with incredulous dismissal, if not the most frightened abhorrence. For half a century in America, the great enemy, “communism,” largely defined the general consciousness. This was the case after the end of the Second World War, and it lasted at least through to the fall of the Berlin Wall, after which said Momentous Event every hitherto timorous official and born-again right-winger transformed himself into a strutting neocon who made the grand, wise, seigniorial assessment about the historically inevitable ascension of the United States to “sole superpower” and clear (revisionist) historical status as Nation Number One of the Twentieth Century, and, well, of All Time. (Cue Dick Cheney and his think-tanker acolytes and senior advisors at Halliburton.) Fox News fans – I keep referring to Fox News and those whom Fox News “reports to” so these viewers can “decide,” because, for me, Fox News is easy short hand for a bunch of stuff – for this reason – that the FS-ers were unmentionably both Marxists and articulate victims of Hitler – undoubtedly have never heard of the FS. If the perfectly coifed, high-skirted “news”-women of Fox, the pomaded Fox News-men, by some miracle (or an airplane intellectual digest of Marxism) and therefore might have heard something about Horkheimer, or Marcuse, it would be only as little shadowy insects under the rocks Roger Ailes would pick up and throw at.

I keep mentioning Fox News here because, as well, Fox News does represent a big slice of the consciousness of Americans today. It certainly isn’t because I like to mention Fox News. If I have to spend more than a second of my conscious waking life thinking about Sean Hannity, or Bill O’Reilly (who, I believe, does, indeed, have a master’s degree from Harvard – summer school, anyway, in their hotel management school), I develop a severe headache preliminary to Tourette’s Syndrome behavior. It’s just that Fox News is very big and has been in America almost since it first appeared on the scene.

In the years between the two world wars, not a great deal of attention was paid to the thinkers and writers of the FS, even though they were preparing masterpieces of iconoclastic scholarship. They did get sufficient attention after Hitler came to power to target them as enemies of the National Socialist state, and, in a particular, quite tragically ironic case, to cause one of them to commit suicide. After Hitler had laid waste to the world and died – perhaps, fittingly, for the FS, himself as a suicide, with Maria Braun, in a bunker in Berlin in 1945 – they carried on, some of them from exile in the United States, but, again, the Cold War literally froze them out of what was then the intellectual status quo. This loose-to-tight assemblage of thinkers consisted of Theodor Adorno, Erich Fromm, Henryk Grossman, Jurgen Habermas (described as representing a “second generation” of the FS), Max Horkheimer, Leo Löwenthal, Herbert Marcuse, and Friedrich Pollock, with Walter Benjamin and Siegfreid Kracauer less directly or formally associated. All were Jews except Habermas and Pollock. “Frankfurt School” and “Frankfurt School of Critical Sociology” were terms later given to this group of like-thinkers, because of their common formal and less-than-formal association with the Frankfurt School for Social Research, an adjunct entity of the University of Frankfurt. All with the exception of Grossman, who was born in Cracow, were German-born – Habermas in Düsseldorf in 1929, Horkheimer in Stuttgart in 1895, Adorno, in 1903, Fromm and Löwenthal in Frankfurt in 1900, Pollock in Freiburg in 1894, Benjamin in 1892, and Marcuse in 1898, in Berlin. The span of years of their births, thus, was from 1895 to 1929. Their published works spanned the years from the time Horkheimer became director of the School for Social Research, in 1930, through to the works of Habermas, from the 1960’s on. Their friends included the Marxist historian, Ernst Bloch, and Gershom Scholem, scholar of the Kabbalah. Antonio Gramsci was a contemporary. Several of them focused in their doctoral work and then their habilitations, or post-doctoral teaching qualification writings, on Kant and Hegel; all wrote in opposition to the idealism of Fichte, Hegel, Schelling and their successors. The Institute functioned until its members fled Germany with the advent of Hitler as Chancellor and the one-party National Socialist state. Accordingly, many of the writings of the members of the FS were written from outside Germany, and the Institute, itself, was reconstituted only in 1949, when Adorno reunited with Horkheimer in Frankfurt; Adorno speaks of himself as one of the “damaged” (Minima Moralia) of his generation of exiles from fascism.

Before going into the matter more deeply, why are these men important? A digression here. Hopefully, you will enjoy it.

Institut für Sozialforschung, c.1930 and 1950

Consciousness

The principle focus of the work of the FS was consciousness.

Consciousness, as suggested or implied, has many different senses. Most attempts at formal definitions are deficient, in my view, even as there are many different approaches to its formal consideration, these several approaches each grappling with saying precisely what it is and simultaneously in completely different ways. (6) In this essay, I do not have in mind formulations or propositions about consciousness that derive from neurobiology. Not do I have in mind attempts to understand it and explain it by thinkers who come from a tradition in British and American philosophy called analytical philosophy. Neither of these approaches, the neurobiological or the analytical (often termed, “linguistic”), has dealt with issues in which a discussion of consciousness was central, issues that were, and are, of particular noteworthiness to Marx, and to the FS, and which, as I intimated at the beginning of this essay, are of great, central, and terrible importance to us now. (7) This is with respect to the sense of political, social, and historical consciousness, a very real panoply, practically speaking; “very real panoply” struggles to be less approximative in its sense; but it is what Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology, would “bracket” as a “natural standpoint” of consciousness. Husserl’s radically empirical phenomenology incorporated a “transcendental ego,” ostensibly free – after phenomenological reduction – of “the natural standpoint,” with its unexamined presuppositions; the existentialist, Sartre, and the post-existentialist, Heidegger, particularly, denied the possibility of Husserl’s transcendental ego. Many people would assert not only that political, social, and historical consciousness are considerations with a great deal to say that is quite relevant, if not “truer” as a context of consideration than any other. (Marxists would agree.) More about the philosophical consideration of consciousness in a bit.

A Theme Park

But first, a digression from this digression that may seem to you yet further removed from the announced subject of this article. I assure you it does speak to the subject of the FS.

In another sense of the word – noting here the “bad faith consciousness” just mentioned – given that the expansion of “capitalist democracy” – read, increasing hegemonic monopolistic aggrandizement of the planet by multinational corporations – such is the businessification of every human transaction, financial, psychological, social, intellectual, and so forth, any entity or undertaking, even a Spike essay such as this, these days must have a “business plan.” (One can envisage this in the waylaid consciousness of today: “first the essay, then the movie,” as literally everything is transformed for the sake of capital. Karl Polanyi called this turn in consciousness “the great transformation.”)

So: the business plan. For it occurs to me there is a way that takes into account reflexively the assigned subject: a theme park.

Now, to the corporate magistri of the theme park industry!, (8) those controlling the images and profit margins of Mickey Mouse, Universal Pictures, Dolly Parton, and so forth: Do not fear! I am not seeking financing yet, so you do not have to worry about a player added to the competitive field. But it is tempting…

I see in my mind’s eye a great dream house, an enormous structure like William Randolph Hearst’s San Simeon – a main building in the theme park – containing within it hundreds of rooms, several with amalgamations of Victorian armchair boudoirs. In addition, there are basements with Steampunkt factory-like apparatus, great pipes and so forth. Upper floors are given over to clothing factories with women workers crowding to the windows to jump to their deaths because the factories are on fire. Mysterious tunnels lead from the main house to out-buildings where physicists split the atom into tinier and tinier particles; both Marx and modern physics look at matter, and it may be they work on roughly similar problems. We certainly have seen how Marx’s experiments to split the atom of history have produced enormous energies, that is, of revolution.

In this wonderful, now ghostly mansion, escorted or ferried around by actors in various disguise (from sans culottes to berets to uniforms with the Red Star on it), one can see what is revealed to be, from strolling around, an enormous, oddly misshapen, but principally absolutely utilitarian – proletarian – architecture. Adjacent to Marx’s study are lecture halls for Horkheimer and Adorno and others; one can imagine Benjamin creeping in from time to time after long bouts of excitement, drink and confession with Bertolt Brecht, Marxist poet and playwright of The Threepenny Opera and founder of “epic theater” (his apartment, with theater props, lights, dimmers, masks, standing everywhere, is nearby, as well). There are two kitchens, one bare of most appliances, indeed, having only a propane stove, with shelves of cans of the soup shown in the illustration, another with all of the appliances and pantries of delicacies for the nomenklatura. Apartments are given over, in varying proximity to or distance from Marx’s great overstuffed armchair, to the constituent parts of Marx’s heritage and legacy, for example, formal, modern, all steel rooms for the structural Marxists – Althusser, Godelier (decorated with African masks) and Meillasoux. A series of apartments shaped like an ice pick is reserved for “Trotskyism.”

We see outside, through the window, a scarecrow looking like Levi-Strauss glaring at someone, a little man with a much taller woman; we are tempted to console him though we don’t know for what. (9) Nearby, Gramsci sits in a prison cell, chewing on the stub of his pencil. Other, smaller mansions are clustered near the main house. The Bolsheviks occupy the ground floor of one, their young, intense, sad countenances drawn with the exaggerated pen of Stalin – an obsessive doodler and talented caricaturist; they each have a bullet hole in their foreheads. Mao, a talented poet, occupies another; in beautiful calligraphy, sheets of his poems are stuck onto the bamboo screen walls; numerous young, beautiful and scantily robed Chinese women come and go, each holding a pot of tea. An ominous, cold-black, star-shaped structure is still under construction in a field of stubble; sounds of Stukas diving, machine guns, and explosions are heard from somewhere inside. A gift shop sells postcards of abandoned, skeletal children struggling with too-heavy oversize suitcases on the Cote d’Azur… As with other semiotics of the theme park, we use the pen and camera of W. G. Sebald for whom color was of great importance because the alienation of the elements one from the other allows for, or dictates as fact of a new physics, color as so unassimilable yet so eye-catching and impossible to do without (with a kind of imaginary poignance) that its deployment in the schemata of the theme park strikes us with both the pain of untreatable cancer and the anodyne of addiction: forgetting, the nagging pain remnant within the merciful death otherwise of memory.

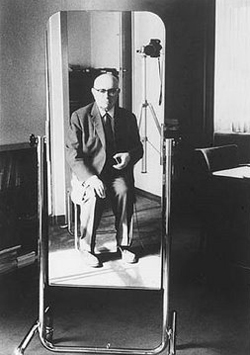

Self-portrait by Adorno

It strikes me that the best design for the contemplated theme park would be to place the entire many square kilometers of it against the backdrop of a giant slightly concave mirror. This is because a crucial pattern in Marx’s thought has to do with a doubling of things, not only his theories of value and of labor but his comment famously revising Hegel, for example: that all important facts of history are repeated, with the second one farce. The concavity of the giant mirror reflects back a distorted whole: without the reflexive, all wholes are false or inauthentic … even with the reflexive that can be the case, a hall of mirrors or infinite bouncing back and forth of the reflection, in pursuit of the synthesis. While I expound on this a little later, suffice to say that one of the greatest illustrations of the principle of the double, or the instant or automatic doubleness of the human Being, that is, as subject or “for-itself” – which is also to say of human consciousness – is the series of woodcuts created by an early contemporary of the FS, the German expressionist painter and founder of Die Brücke, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner; Kirchner may be the Episteme for the first half of the twentieth century, the last decades of the Modern. The series, “Peter Shlemihl and his Shadow,” iconically represents the impossibility of wholeness. About this idea, by the way – intriguing testimony to the continuing deep power and relevance of FS thought – in his Minima Moralia, Theodor Adorno observed how the Fragment shows more than the original Whole: “The splinter in your eye is the best magnifying glass.” A seeming, great conundrum: the greater – emergent – substance is that of the shadow or the double – the antagonist – when placed next to the original or agonist. The notion, again is Hegelian: the thesis always holds within itself the seed of its destruction, which is the antithesis, which, in turn, holds within it the further, unifying step of the two, the synthesis. For the FS, renowned for their “pessimism,” the synthesis is an existential impossibility. The curious, somehow deeply disturbing sense of being second-hand is the overriding experience of collapsed modernity. This is hugely, hugely important to grasp if you wish truly to understand modern-to-postmodern consciousness and history, that is, epistemically. Big word, very key, these days. But perhaps best put off for another article.

We can keep on walking through the theme park, but we’re likely getting tired and could use some sustenance, or a couple of cold ones, maybe. As we leave it for now, I suggest the theme park dedicated to the Great and Terrible Man does have much to be said for it. For one thing, there are so many fun and funny ways to collect the admission fee. The transaction serves, in and of itself, as a reminder – reiterated by the situating of the theme park away from everything else, not a tree, other building, not even a locust for a new John the Baptist, nothing, to suggest a context of “civilization” into which it and its subject matter are integrated (an abandoned combine farm – its farmers long-since bought out and downsized – could be purchased in the vast plains of America’s midlands) – that the medium still is the message, that transactions based on capital wipe out everything else, (10) that digests of experience and life are prized, not merely required, by the New Man, Consumer-Man, who – if we are to believe those wistfully hopeful that “Late Capitalism” is soon to be “The Late Capitalism,” as in the deceased capitalism – is already becoming passe. (I hate to point out to these good folks that capitalism seems to create its own worlds.) Another benefit of our theme park of Marxism is that it anticipates the farcical second appearance of the lebenswelt, the “lifeworld,” “lived experience,” (11) one of the hallmark notions of continental philosophy, as elaborated in modern times early on by Husserl and then much later again by Habermas – in that it makes the lifeworld a consumable, with a price on it. As pre-digested experience is what the palate of the Right greatly prefers, I might be able to make some money for our stockholders out of the contemplated theme park, and isolate this most extreme duplicity for study by (inevitably leftist) social scientists who appropriately have been determined to come mainly from disenfranchised or marginalized peoples, Jews, for example. (End of digression. I hope you enjoyed it. I hope you’re still chugging away with me.)

The Entirely Reasonable Pessimism of the Frankfurt School of Critical Sociology

That Marx was so important in the opinions of the members of the FS should not be taken for granted nor their individual contributions diminished in whatever way because of the secondary or commentator character of much of their work. Rather, it seems the truer and more responsible assessment to make of the School that its members understood Marx better than his other interpreters, followers, and critics – because they were able to take Marxism and go forward with it in new and concrete ways, and, in so doing, they recovered for us or reoriented us to evaluate, once again, the usefulness and relevance Marx’s writings and ideas continue to have, or not to have, for us.

The FS came into being in the years between the two world wars – notable peaks of human slaughter in a century that witnessed 365 million lost due to wars – and at the beginning of the worldwide Great Depression. Hence, the undue “pessimism” they have been accused of is the more remarkable for its having been overcome at least as forecast. If recognizing a fault in us of morality (fairness, justice, amelioration of human suffering) is insufficient to change our ways – which the FS critiques and studies can help us to do by showing us how we think wrongly about matters social, economic, political, and aesthetic – then the vital threats to our physical survival should at least require us to take another prolonged and serious look at the extraordinary inequalities of Western society internally and by comparison with the rest of the world, inequalities that threaten human existence; the productions of the FS-ers provide conceptual tools to help us understand our situation and, hopefully, if not solve our problems, point us in a better direction – toward a more just social model. How do they accomplish this?

As consciousness is a key topic for Marx, and more particularly for the FS, some more elaboration here is called for. If Husserl erred with regard to the transcendental ego, and there is, indeed, no such thing as “pure consciousness” (it is a great credit to him that he emphasized the “intentionality” of consciousness, which made clear that one cannot be conscious unless there is some thing that one is conscious of – consciousness is always and only intentional, as he put it, in the Cartesian Meditations), it was not not only completely justified for Marx and the FS to stress particular consciousness, for example, a consciousness in which the Western Enlightenment has been prominent if not dominant. It needed to be critiqued.

The Frankfurt School theorists took a tack with what otherwise is one of the big problems with critical theory – and romantic, or continental, philosophy (the philosophy that sprang from Descartes and passed through the German idealists – more on this a bit later), and that manifested as a common, early misinterpretation of Marx – the positivist assumption that man, and human consciousness, are privileged or special emergents, that can or must be considered untouched by physical (e.g., biological) or material constraints or frames of interpretation. Without proper attention to the issue we must ask not what makes human consciousness unique or special but is human consciousness unique or special? Even if we resort to the cogito (see below), we are assuming human consciousness is privileged, and that it stands apart from any consideration other than its own consideration of itself – bracketing all considerations from a “natural standpoint.” This is the phenomenological and existential approach, and it would seem, then, to be one reason why romantic philosophy, as it ultimately manifested in Marxism, inevitably leads to activism. In Reason and Revolution Marcuse wrote: “Hegel’s system … brought philosophy to the threshold of its negation and thus constituted the sole link between the old and the new form of critical theory, between philosophy and social theory.” Such a statement refers to the biased, worldly or “actual” involvement of the thinker/philosopher in society and history, which is precisely what Marx implies in the Preface to the First German Edition (of Capital), (12) and what he affirms, outright, in the Theses on Feuerbach: philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.

More to the specific point here, to truly understand the content of the thought of the FS, as suggested earlier – and while many hints and ideas already have been given – one needs to grapple with the term and concept, consciousness. This is because so much of what they wrote about, extrapolating from Marx, in order, they believed, properly to strengthen and protect the great edifice of the Master, was also because consciousness was where the relevance, with renewed and even greater significance, lay, that is, to consciousnesses, plural.

As articulated in perhaps the key contribution of the FS, Horkheimer and Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment, “domination” was the enemy of authentic consciousness. How does this reverberate within Marxist thought which, otherwise, has seemed to stress historical cause located on the substructural, material, level?

One of the most important, if not the most important, issues in and ramifications of later Marxist thought falls under the heading, critical theory – ironically a rather uncritically examined notion that includes both sociological concerns (e.g., consciousness as part of the work of authentic social – socialist – action, as well as aesthetic, e.g., “post-modern,” literary theory); here I mean the term with respect to one particular denotation, the turn – or the reflexive – in consciousness by which one becomes aware of oneself and the constitutive (Husserl again) nature of consciousness. An immediate insight follows: that positivism is an insupportable metaphysic because it springs from a non-transparent, non self-aware, consciousness. (You can understand how “critical,” then, also means “careful” scrutiny but not merely that: careful scrutiny with one arbiter or standard – concrete historical process, that is, dialectical process.)

In our theme park, by the way, one of the first busts we encounter of Great Men predecessory to Marx is Descartes. This great splitter between the scientifically rational and the irrational also was the enunciator of a momentous discovery, that of the reflexive or the critical, which we have encountered several times already in our theme park of Marx. The cogito, as it is often referred to in philosophical tracts – taken from the statement, cogito ergo sum – was an a priori and self-evident insight, simultaneously instantly, transparently clear and extremely penetrating or deep, as it led to the secondary, necessarily implied, conclusions of the existential. These ramifications and permutations, thereafter, were explored by Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Schopenhauer, Husserl (very explicitly in the Cartesian Meditations), Heidegger, and others, such as Gadamer and Ricoeur, writing, for example, about the hermeneutic. Contra sophist nitpickers and the analytic philosophers, in general, there is a straight, intuitive line one can trace through all of these thinkers from the self-given, a priori insight of the cogito, as each, in turn and with a particular field or discipline or body of thought, amplified and elaborated on it. Contra same, there is no negating this line of thought because it is completely and self-evidently logical and true, and exclusively so with regard to the radices of philosophy, which is to say: if a consciousness is going to study either the formal philosophical categories of ontology and epistemology, he finds he is doing to do so only in combination, that is, both ontologically and epistemologically. Again, making the commitment to do so must always begin with the cogito, for it is the only self-evident proposition in the universe of assertions and assumptions of what must be considered the most fundamental intellectual undertaking of all, philosophy … well, most fundamental short of social revolution. Although their emphases were not purely philosophical but, rather, sociological, historical, and aesthetic, the members of the FS wrote entirely within this tradition and this trajectory.

Not to belabor the point, the fundamental insight to grasp is that every beginning in pure thought must spring from the cogito – even, as I say, as it leads ultimately to action (cf. the last lines of Sartre’s Being and Nothingness). The concrete things of the universe are made concrete by the so-called subject – by consciousness, and, accordingly, there is a double action entailed of man-in-the-world, which, as Heidegger, pointed out, is the only way we humans are. This double action consists of the world, first, and then the world observed and constituted – discovered and created simultaneously, which appears to be an impossible contradiction but in truth is not so – it is only contradictory because of the existential condition of the for-itself.

The fact that in his later years Heidegger chose to devote his time to thinking about poetry – using Hölderlin as the particular subject for his speculations – is understandable; it is particularly with language that he believed is the clue needed to untie the Gordian Knot of the hermeneutic. This is because language, and, particularly exemplary, the language of certain great poets, expresses the emergent – the shadow, the double, the antagonist. In so doing is revealed how the antagonist is bigger and more substantial than the agonist. This is to say that the antithesis will always be larger and more substantial, in existential reality, than the thesis. There is no negative symmetry. The fact that completely occupying the meaning of the thesis sows the seeds of its destruction does not mean they are equal; they are unequal. Sartre’s dichotomy of thetic and non-thetic also makes this clear; the non-thetic corresponds with “lived experience.” (As much as Heidegger was fascinated with poetic language, I very much regret that the FS writers did not respond to German expressionist painting and, specifically – a personal wish – to Kirchner’s “Peter Shlemihl,” which I suggest is perhaps the most lucid and touchstone-living work of art that illustrates these tensions.)

All of those associated with the FS were linked by commonly held concerns about the distortion, and vitiation, of Marx’s thought and work. Subsequent interpretations and/or quite different formulations after Marx’s death were based either closely or not so closely on Marx – the first utterances by Marx and Engels – the “primary sources” – are said to be “classical Marxism.” Greatly simplifying and noting only the most prominent individuals and schools of thought, in the immediate period after Marx’s death in 1883, the spotlight shifted to newcomers on the stage, for example, to most of the revolutionary groups in Czarist Russia and, later, in post World War One Germany, to Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. Already, formally denoted “socialist” groups and movements, responding to the contradictions and emiseration of capitalism and neo-liberalism, had sprung up, for example, the Fabianists in England.

In more theoretical terms, in addition to arguments about what Marx meant, the debates were about how to proceed (e.g., Lenin’s What Are We To Do?, composed between 1901 and 1902); there was an urgency about Marx and his thinking because finding a way structurally to alleviate human suffering, as an outcome, particularly, of industrialization, was a central motivation – a motivation both instinctive or reflexive and mentioned as a matter of course by Marx, himself. Accordingly, early post-Marx debate revolved around such matters as permanent revolution or revolution-in-one-country (Russia) and about peasant vs proletariat revolution. Debate focused, also, on epistemological and other more purely philosophical matters. In addition to the nature of consciousness, the idea of the “dialectic” and Hegel’s formulations with regard to historical process, the struggle between the “classes” (proletariat vs bourgeois), the nature of history, materialism vs idealism, history vs process, and so on, all received more or less their due attention and moments, singularly and recurring, on the stage.

The members of the FS were concerned with what Marx meant. They were as tightly knit or as loosely bound as these intellects, mostly quite in sympathy with one other, were permitted, found, or required by the arguments and intellectual advances themselves – they were internally consistent and logical as much as they derived naturally or organically from Marx. They chose as their focus the novel, but now assumed fundamental, corrections to and reapplications of a Marxism that not only had, with Stalin, gone majorly bad but, in addition, more generally, been diverted or distracted by the theoretical interpretations of dogmatic, reductionist, supposed orthodoxy (at the time what we now would see as unreconstructed opportunist or ad hoc “communist” revolutions in single countries – the Soviet Union – contra Trotsky’s world revolution). In addition, the FS-ers sought to remedy the faults or grave missteps of positivism, materialism, and determinism that were threatening to derail the relevance of Marx and Marxism. It is probably important to keep in mind that of these three sins, positivism has been the most insidious, ironically, in its theoretical malefactions and still the most useful to deconstruct, for example, for the sake of the hermeneutic, but, fundamentally, because positivism has proven to be the hardest nut to crack, with Anglo-American analytic philosophy, such as logical positivism, and its successors, having many adherents dismissive of the reflexive impulse and insight because they simply do not seem to understand it.

And, as far as we can tell – without the full hindsight yet of a history extending into a post-capitalist age – the truly enormous transformations of human society and humankind wrought by the technological revolution or the developments of the information age, as well the planet-wide degradations of the environment, and human overpopulation – given all of these wholesale transformations of human life on Planet Earth, it is a wonder that this relatively modest, soberly pessimistic body of commentary and analysis, by contrast not seeking great attention to itself within the context of the vast rightwing-conspiring post-Reagan epoch we now live in, has survived at least to the extent that its ideas, again, seem so sufficiently intriguing as more than a little appropriate and applicable still – and particularly now, when the epistemic consciousness is so ransacked and set against itself.

Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno in 1965

Some of the Main Works and Useful Theses for Today’s Hopeful and Otherwise Lost in a World of (Other) Theme Parks … and a Soapbox Rant, or Two

Just as I urge, in this walk-through of the rooms devoted to the FS in the theme park of Marx, renewed or new attention to particular FS-ers, I want to underscore that each of them contributed important theses reinterpreting their Master but also going beyond where he had time or energy to look as they also analyzed social forms unexperienced by Marx – totalitarian societies (National Socialist, inspired by Pollock’s habilitation, and Stalinist, as dissected by Marcuse) as well as the Western consumer societies, for example.

Arguably, the most influential has been Horkheimer and Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947). In addition to an affirmation that a focus on consciousness is an essential component of Marx’s contributions, the principal insight of this work was that hoary Western intellectual advances, primarily the Enlightenment, were partly formed by and considerably contributed to precisely the negation of the kinds of values explicitly proposed; this insight represented a reflexive or self-aware distancing from enormous, blanket, unexamined presuppositions (cf. Husserl). One recent reviewer wrote of the “continuing relevance” of the work, which describes “…modernity as a world of restricted thought and suppressed alternatives…” and, therefore, as needing to be overthrown, noting the Dialectic’s emphases on “…the all-pervasiveness of commoditizing social relations, the totalizing presence of cultural production, and the domination of the critical faculties of rational thought” (ibid.) The fundamental point of the book is the critical or reflexive stance of its authors apart or outside of the Enlightenment “myth”; the truly reflexive or critical which was only forecast or foreshadowed by Marx (working as he did, however, directly within the romantic tradition, in his case, of Kant and Hegel), described by Horkheimer and Adorno within but apart from Enlightenment “rationality” (as much as self-awareness permits), then, is a key contribution made many decades ago and that has special relevance now, when the domination of capitalism even in mass consciousness seems so complete and unchallengeable that its puppeteers seem not to fear the image of absurdity – as cut-and-paste disconnected pieces of consciousness (cf. Benjamin’s “Arcades”) in hilarious juxtaposition. (Clicks of the tv remote through the hundreds of channels available now provide the most extreme contrasts of content and affect, the only glue holding them together, a glue that is also a mindless soporific, the selling of things.)

Adorno on his own produced the Minima Moralia. Written during World War Two but not published until 1951, this was composed as “aphorisms,” or short definitions of common words and phrases that served, for Adorno, as inspirations for what might be described as blues or jazz riffs of usually melancholy mood on the sorry state of things in modernity – a “damaged” and treacherously hypocritical and unreflective consciousness and existence.

In this way, Adorno echoes another FS-er, Walter Benjamin. His “arcades project” is only partially published, rescued from National Socialism and Benjamin’s suicide which occurred when he had escaped the Gestapo by slipping into Catalonia but was informed, mistakenly, that he would have to return to Vichy France. The arcades are the stalls, in 19th century Paris, where, Benjamin posits, for the first time the modern age of capital was transforming, overwhelming, consciousness by diverting it into the disjointed stream of the commodity. Projected onto the modern consciousness in the arcades – stalls where advertisements appeared and where things could be bought, things the individual never knew existed, and certainly never knew it, or he, or she, “wanted.” This “freedom” fragmented not only consciousness but identity. The only common factor belonging to the things for sale in the stalls was that they were for sale. There was no other organically connected ideology than commodity and profit. The Paris arcades were the kernel, Benjamin wrote, for “the mechanical reproduction” of consciousness, the effect being the passing of the self into the limbo of things, down endless alleyways and sidetracks. The commodified consciousness has come to define modernity, collapsed modernity, and post-modernity. As capital has continued to transform the world, now, with advanced capitalism, consciousness has been digitized on the internet where “virtually” (remember “lived experience”?), in ever more exact fashion, with bots tracking our buying impulses, capital not only finds “what we want”but constructs and instructs our identities by the things we are made to want to buy for the sake of more capital.

Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man makes the observation, so relevant today, that consumerism represents a profound form of alienation in capitalist societies; Eros and Civilization argued that Freud and psychoanalysis represented “critical social theory.” Marcuse’s first work, and one of the earliest book publications of the FS, was Reason and Revolution: Hegel and the Rise of Social Theory (1941), which argued that Marx and the line of critical thought he promulgated was the correct and natural consequence of Hegel.

Habermas – a “second generation” FS-er, and student in the 1950’s of Horkheimer and Adorno at Frankfurt (in the reconstituted School for Social Research) – is the Grand Old Man today of German philosophy. Knowledge and Human Interests (1968), his first comprehensive statement about critical social theory, was descriptive or “anthropological” in that he discerned three types of “knowledge-constitutive interests,” the elucidation of which permits the third of these, “emancipatory interest” to “[overcome] dogmatism, compulsion, and domination” (cf this Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry). Theory of Communicative Action (1981) remains his major work. As second generation but still formally of the FS in affiliation and training, Habermas seems to depart from Marx’s prescriptions of the dialectics of class conflict, stressing, for example, that rationality as realized in communication between individuals and groups, can defeat or circumvent the negatives of modernity and postmodernity, even as his propositions remain socially grounded and meaningful rather than what social scientists have long since dismissed as “methodologically individualist.” (“Economic Man” is an artificial creation; if we are going to atomize humanity, far closer to reality, or the reality those of us who consider that we like and value human beings, and life, itself, would prefer, I might suggest to you, is “Social Man.”)

In our theme park, of course, are countless soap boxes. I am now standing on one of these, as I call out to you on my bullhorn:

These are but some of the major contributions of the FS. I urge Spike readers to explore these and other works that I have just touched on here or not had the space to mention. All are of precious value, historically. But, much more importantly, vitally importantly, taken together, the books and essays of the FS offer great spurs to a fully dialectical “enlightenment.” With their guidance, we can understand how too many of us have been deconstructed and constructed for the sake of capital. The commercials on television, in general, and now on the internet – teaching us in the First World that self-fulfillment comes from buying with our credit cards stuff that ultimately is destroying the world, as consumerism eats up the planet, teaching the Third World the same thing as we in the West hopefully learn to reject the name, consumer, and reject the process of consumerism, and, simultaneously, continuing without discrimination to emiserate all and anyone for the sake of the Blankfeins of Wall Street, and the Murdochs of the media and “news” world, and the Koch brothers of toilet paper, and energy, and whatever else it is these funders of the Tea Party movement, make and sell us … well, we can learn to turn these off. We can learn to resist as one, enlightened mass: the People…

Okay. Not yelling anymore.

But these are the kinds of activism the FS permits us to understand and consider. The FS also, again, points us back to Marx for fundamental and critical analysis of historical – dialectical – social process.

Placed again in formal context, a true assessment of the FS as a whole, its impact and heritage today, allows us to understand where both continental philosophy and Marx went before and after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Marx, particularly, was an exponent of great social action, but so it seems have been the masses in Tunisia and Egypt just these past few months.

The point I wish to make is that whatever you may think you think about Marx and Marxists it is still the case that your consciousness does not have to be fractured, or fragmented, or bought and sold. More people tan one might suspect believe that things have reached a critical stage. If you feel the stirrings, the same beleaguerment and frustration that I feel, just maybe like the revolutionaries in Egypt these past few months, you can help start to make something happen. Incidentally, with this encouragement I am entirely true to the continental philosophy this article I am sure made clear I adhere to: the thought, as I say, straight from Descartes, forerunner of the Great Enlightenment, the thesis of which the FS showed us sowed the seeds of its own destruction, through to today.

Conclusions: Leaving the Park

There are various doors out of the theme park. The type of exit depends on how well the visitor to the park scores on a little quiz given by smiling docents. Obviously you need to acknowledge the outstanding likelihood of discovering insights of extraordinary relevance not only to understanding but also hopefully helping to resolve some of the almost unspeakably horrendous and terrible contradictions in society and consciousness today. A passing grade, by the way, opens a door leading to an invitation to join a commune of attractive, passionate, men, women, and children, each possessing a unique talent – each of them absolutely fascinating and commendable (musician, physicist, chess player, athlete, plumber, agronomist, poet, truck driver, etc.), each not merely accepting of but welcoming the dictum, “To each according to need, from each according to ability”; in the background, an orchestra plays the Internationale. A failing grade, however, opens a door shunting one down a crude concrete tunnel into a sty full of starving pigs.

We have seen the monsters that “communism” can produce. By now, surely we know well the monsters that “capitalism” produces and which, contrary to bourgeois faith, appear to be far worse. Is it really necessary to continue to point out that the cheers of the capitalist brokers and cynical so-called ideologues on the right are hypocritical, red herring, lies and cant, that, for example, “communism” is bad because of the likes of Stalin or Mao, or, incredibly more stupidly, because of the supposed slippery slope of “big government,” and that “capitalism” – synonymous with democracy (not!) is best because (a Hobbesian) “human nature” unchangeably is what it is? If these hypocritical repeat-dissemblers and disinformers, cunningly misinform, in order to mislead, those led also by these patriots to not think, to not question – the “Christian,” NRA- and NASCAR-devoted, “pro-life,” Obama-doesn’t-have-a-US-birth certificate types – one wonders how it must still be necessary to point out that what Marxists with justification (read the history!, I suggest to you) call the “capitalist-imperialist wars” of the last century killed ten times as many human beings than one can lay at the feet of Stalin and Mao combined. By saying this by no means am I suggesting that Mao and Stalin were in any universe to be considered good guys; no, how they used their power made them into great monsters. But one wonders how it must still be necessary to point out, as those writers and thinkers of the Frankfurt School of Critical Sociology, despite their general pessimism – or, perhaps, dialectically because of it! – have been implying: that Socialist Man is possible. From the worst can come the best. The human species continues to evolve: evolutionary biology affirms this. The seemingly revolutionary uprisings in the Arab world going on today may begin to confirm this. We must wait to see if these revolutions are only more the wannabe turmoils of Consumer Man, that is, waylaid and sabotaged and distorted against themselves by capital and what Habermas and others of the FS term, simply, The System.

The FS’s members were in fundamental agreement that Marxism largely had fallen to narrow parroting in defense of orthodox Communist parties and regimes. Epistemologically, they were concerned that positivist assumptions still prevailed. And they were motivated, as well, by the fact that “traditional” Marxist theory could not adequately explain the turbulent and unexpected development of capitalist societies in the twentieth century – “traditional,” meaning, in this case, extrapolations from and interpretations that did not necessarily follow or agree with what Marx, himself would think or might have thought. It is important, therefore, to emphasize that as much as Marx and his theories continued then and continue now seem to have extraordinary relevance and to provide invaluable insight into historical and social process, the FS has formed what must be considered an essential part of the efforts, through time and space, of humans to build a better, more just and equitable, society. Of course, utopia inevitably becomes dystopia, and any huge shift in consciousness is not likely to alter Trotsky’s opinion of the tailless apes. But one must believe that only from such realistic pessimism, again, one of the keynotes of the FS, might we as a social species advance. The “critical” means self-aware – therefore, hopefully, continual checks on how we are doing. That the greatest culmination to date of the romantic impulse in Western thought was the work of a onetime Nazi, Heidegger, both confirms the pessimism of the FS and gives us hope that out of the black hole can come the long-awaited advance. Lashed by the legacies of world war horror, by death squads and genocides in Central America and Central Europe, in Africa and Asia, ridiculous hypocrisies of advertising and marketing as foretold by Benjamin’s “arcades” for contemporary consciousness, the fragmented consciousness of consumerism, will all this be overcome? In the worst are the seeds of the best? And if we can speak hopefully but realistically – despite the current prospects – what would or will the New World look like? The fine-tuned sensibilities and insights of the Frankfurt School of Critical Sociology may represent the type of consciousness that prevails, sooner or later.

Members of the Frankfurt School (date unknown)

Notes:

- The “Reverend” Pat Robertson advocating, during one of his television sermons, employing a sniper to “take care” of Hugo Chavez, president of Venezuela.

- Is there anyone who would suggest differently about the religious affiliation of Fox News employees?

- István Mészáros, who, in Socialism or Barbarism (1995) does extend the prophesied downfall of capitalism, brought about by the “internal contradictions” of same, to the ruination, ecologically, of the world.

- Having said this, some convergences are curious. The doomsday eschatology of the “Christian” right and the despairing left converge, although, for the latter, without the chiliasm: fire and brimstone for moral failings conflate with a now seemingly unavoidable world-wide environmental calamity. Another point in curious agreement: lack of awareness or understanding – proper consciousness – of the real or true situation is what has gotten us into such dire trouble.On the one hand, if more people believed in Jesus we would win our wars, powerful bad enemies of Christian America like Hugo Chavez would die – in his case leaving us his Venezuelan oil – and the American way (including multinational corporations) would be able to keep on the march certainly into all those places around the globe that fall within the sphere of “American interest,” which is pretty much the whole world. Everything would be just hunky-dory. Or almost so. Social security and Obamacare socialism still would have to be eradicated so that “taxpayer money” would no longer be used to prop up, artificially, those who otherwise are less “fit.” The invisible hand would take care of them – that is, by not taking care of them.

- Mark Lilla, “Slouching Toward Athens,” The New York Review of Books, June 23, 2005.

- This inquiry has been pursued notably by philosophers such as David Chalmers and David Dennett, but also by mathematicians such as Roger Penrose, working with anesthesiologists – in the latter case, postulating that “quantum action,” such as “tunneling,” “entanglement” or “superposition,” occurs in neuroanatomical “microtubules.” In other words, consciousness is considered as something in and of itself, that is, without contingency – they call understanding it the “hard problem” – by which “subjective” awareness, in the abstract, happens: How, why, or in what way does the experience of seeing the color red differ from the “fact” of red as a wavelength of light? In an unreconstructed or analytical philosophical manner, this often is called “reflexive,”meaning simply, more or less, “self-aware.”

- Sartre’s famous, “consciousness is what it is not and it is not what it is” is more a characterization than a definition; it contains a clue about how the dialectic of the “for-itself” and the “in-itself” operates and, hence, how the constitution of the world does not mean that the world is not already “there.” For, it is both – a seeming impossible contradiction until one realizes the dialectic precisely does not fix but moves back and forth as from two poles; the hermeneutical circle dilemma applies here, which nis not a dilemma, at all once one realizes the operations of consciousness in-the-world.

- I scratch my head at the daffiness of capitalism today. Check this out: http://themeparks.about.com/ for more on the subject of theme parks. But is it so daffy? Maybe crazy like a fox? Can theme parks be consonant with Evil? My intuition says, yes.

- The famous feud between Sartre and Levi-Strauss – basically as to whether consciousness effectively or completely is constructed or not – was a feud fought at the wrong place at the wrong time. The ultimate, and seemingly irreducibly impossible contradiction of the true whole of Being remains: that between the absolute concreteness, the “radically empirical,” to cite Husserl, on the one hand, and the constitution (Husserl, again) or construction by consciousness of What Is. Heidegger tortuously wrote about this. Marx – and his estimable followers, the apostles of the Frankfurt School – emphasized the dialectic precisely for this reason. And, to give Sartre his due, the existential does lead ineluctably to the “mystery of action,” as he noted at the end of Being and Nothingness.

- I keep reminding myself to research how Karl Polanyi deals with Marx… Someone, please, write in to Spike about this.

- “Lived experience”: one of those fascinating, seemingly impenetrable, or ridiculous, turns-of-phrase from later – existentialist – continental philosophy that can only be parsed by those who understand the implications of the original insight of Descartes, the cogito.

- “The social statistics of Germany and the rest of Continental Western Europe are, in comparison with those of England, wretchedly compiled. But they raise the veil just enough to let us catch a glimpse of the Medusa head behind it. We should be appalled … if … commissions of inquiry into economic conditions … were … to get at the truth … the exploitation of women and children … housing and food…” (1867 [Capital 1977:9]). The Communist Manifesto (1848) also, of course, makes no bones about promoting revolutionary action.