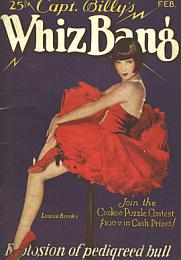

Robert O’Connor enters the madcap publishing empire of Wilford Hamilton Fawcett, home of Captain Billy’s Whiz Bang and Captain Marvel during a golden age of comics

Captain Billy’s Wild Creation

The musical The Music Man is chock-full of references to the American Midwest and the America of 1912, especially in the song ‘Trouble’, sung by its main character, the smooth-talking con man Harold Hill. The most topical of the references he makes in that 720-word song are to Dan Patch, the famed racing horse and when he is telling the concerned mothers of River City, Iowa of the signs that their sons might be headed for trouble: “Is he starting to memorize jokes from Captain Billy’s Whiz Bang?”

Audiences today might not know what that is, but Captain Billy’s Whiz Bang was made by a company in Minneapolis. It’s also an anachronism, since the magazine began in 1919. The company that made it, Fawcett Publications, was also responsible for creating Captain Marvel, who at one time was the most popular superhero in America (beating even Superman) and the first-run paperback novel.

Whiz Bang

Fawcett Publications was the creation of Wilford H. Fawcett. Fawcett had a wild and eventful life. He was born in 1885 in Woodstock, Ontario, but grew up in Minnesota. He ran away from home at 16 and joined the army, lying about his age. He was sent to the Philippines and fought in the Philippine-American War, where the rebels against the occupying Spanish turned against their new occupiers. Some accounts, including the disclaimer inside Whiz Bang say Fawcett fought in the Spanish-American War, but that war was over by the time he got to the Philippines.

An injury sent him home where becoming a police reporter for the Minneapolis Tribune (some sources say the Minneapolis Journal). He also fought in World War I, writing for the army newspaper Stars and Stripes. The newspaper didn’t print bylines, so there’s no way of knowing what he wrote for them. It was during this time he got the name “Captain Billy”. Stripes editors Harold Ross and Alexander Wolcott would start the New Yorker magazine in 1925.

An injury sent him home where becoming a police reporter for the Minneapolis Tribune (some sources say the Minneapolis Journal). He also fought in World War I, writing for the army newspaper Stars and Stripes. The newspaper didn’t print bylines, so there’s no way of knowing what he wrote for them. It was during this time he got the name “Captain Billy”. Stripes editors Harold Ross and Alexander Wolcott would start the New Yorker magazine in 1925.

When Fawcett was discharged from the army, he started Fawcett Publications in the Minneapolis suburb of Robbinsdale. He began publishing Captain Billy’s Whiz Bang in October 1919, intended it to be a joke magazine for servicemen in Robbinsdale and the surrounding suburbs. A “whiz bang” was a bomb that had been used by Americans during their brief participation in the war.

Fawcett didn’t forget his military roots, and dedicated each issue to “the fighting forces of the United States, past, present and future.” He also included a quote from Theodore Roosevelt at the beginning of each issue: “We have room for but one soul [sic] loyalty and that is loyalty to the American People.”

The magazine took off, and gained a nation-wide readership. In December 1921, Whiz Bang said it had 1.5 million readers. By 1923, according to a 1940 article in Time magazine, it had a circulation of 425,000. It sold so well that other digest-sized humor publications like Charley Jones Laugh Book took inspiration from it. The magazine declined in readers in the 1930s when readers took to the more sophisticated humor of magazines like Esquire and the New Yorker.

Whiz Bang would start with a long piece by Captain Billy, called ‘Drippings from the Fawcett’, talking about his life and what he’s encountered in it, sort of like an editor’s note, but more informal. His porter, Gus, made frequent appearances in these notes, as did his bull Pedro. Pedro died some time in 1921 and the magazine printed letters of condolences sent in by fans.

Its humor was lowbrow and bawdy. Many of its stories featured ethnic characters and were written to reflect the dialogue. ‘The Adventures of Sven’ appeared in 1921 for a short time and the prose had a Scandinavian color to it. When African-Americans appeared in stories, their dialogue had slang inflections as well. They also had jokes about drunks and alcohol well after Prohibition went into effect.

It had a section for advice from the Captain, where he would answer questions sent in by readers. Some of the questions he answered included:

Can you give me the technical name for snoring?

Sheet music.

and

What is Golf? – Ignoramus

Dear Ig: Golf is a game where old men chase little balls around when they are too old to chase anything else.

There was a section for poetry, but shorter, wittier and dirtier verses were put in the margins of the magazine, like this one:

Sleep, baby, sleep,

You’re mama’s pet;

Though your father voted dry,

You were always wet.

And this

Listen my children and you shall hear

of the midnight ride of a bucket of beer

– up the street and down the line,

I’ve got the bucket; who’s got the dime?

Longfellow’s famous poem is parodied again in May 1921 with W.K. Edwards poem ‘The Midnight Glide of Pauline Revere’, which tells the story of Paul Revere’s wife during his midnight ride.

The magazine had a regular section on Hollywood gossip, focusing especially on relationships – the marriage between Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks and the breakup between Charlie Chaplin and his first wife, Mildred Harris were hot topics. If it wasn’t about Hollywood, it was about the latest stir in Broadway.

A regular contributor was Rev. G.L. “Golightly” Morrill, the founder of the peace church in Minneapolis. Morrill was just as eccentric as Fawcett, he would travel the world and give lectures on scripture that involved vaudeville performances, slideshows and music. During these tours, Morrill would send descriptions of the places he visited to Whiz Bang, describing the sins of the various places. In the August 1920 issue, he describes the practice of West African witchcraft in French Guiana.

On a 1922 trip to Havana, which he called “the land of liberty – personal and otherwise,” Fawcett learned that Cubans didn’t like Morrill after he called Havana a “fool’s paradise – a lunatic limbo for people with loud clothes, lots of money, loose morals and light heads,” among other things, in the October 1920 issue of Whiz Bang. When Morrill died in 1928, a phonograph recording of his voice preaching his funeral service was played at his funeral.

Starting in 1921, the magazine had a section called ‘Whiz Bang* Filosophy’, which had short bits of advice twisted around humorously, like

After man came woman, and she has been after him ever since

and

Before a man marries, he swears to love; after marriage, he loves to swear.

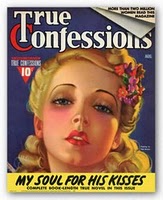

Almost immediately, Fawcett started publishing other magazines. They began True Confessions in August 1922, in the wake of the success of Dorchester Publishing’s True Story magazine, which offered true, or purportedly true, stories written by ordinary people about their experiences. True Confessions eventually had a circulation of two million a month. Promoting it in Whiz Bang, Fawcett called it “a baby brother to Whiz Bang.” Fawcett’s longest running title, Mechanix Illustrated, began in 1928. It began as a magazine of popular science to compete against the older and more popular Popular Mechanics and Popular Science. Mechanix gained fame for its ‘do-it-yourself’ articles and a focus on hobbyist topics.

Almost immediately, Fawcett started publishing other magazines. They began True Confessions in August 1922, in the wake of the success of Dorchester Publishing’s True Story magazine, which offered true, or purportedly true, stories written by ordinary people about their experiences. True Confessions eventually had a circulation of two million a month. Promoting it in Whiz Bang, Fawcett called it “a baby brother to Whiz Bang.” Fawcett’s longest running title, Mechanix Illustrated, began in 1928. It began as a magazine of popular science to compete against the older and more popular Popular Mechanics and Popular Science. Mechanix gained fame for its ‘do-it-yourself’ articles and a focus on hobbyist topics.

Fawcett made other magazines that were less successful. Mystic Magazine, which focused on occult topics for a women audience, lasted five issues from November 1930 to March 1931. It was edited by August Derleth, who had just graduated from the University of Wisconsin. Derleth is best known as an associate of H.P. Lovecraft and the founder of Arkham House.

Pulp illustrator Norman Saunders got his start at Fawcett during this time. The company moved from Robbinsdale to Greenwich, Connecticut in 1934.

Robbinsdale to this day has a four-day celebration of the publishing house, “Whiz Days.” It happens every year the weekend after the 4th of July, with a parade, royalty, arts and crafts booths and more. The city’s website on the event says it was a celebration of the city started during the Second World War, and was named after the publishing house.

Fawcett bought a cabin near Pequot, Minnesota in 1921 along with 80 acres of land next to Big Pelican Lake. In 1922, he opened the Breezy Point Resort on that land. While it was advertised in Whiz Bang, it attracted mainly wealthy and famous customers. Clark Gable stayed there, as did future President Harry Truman when he was a Jackson County court judge.

Fawcett’s company was a family affair, as described in a family history written by Billy’s son Roger in 1970. Billy’s brother Harvey ran Fawcett Publications from its inception until he was fired in 1923 for taking dollar commissions on tons of paper purchased. Billy’s brother Roscoe, who stayed until 1936, replaced him. Captain Billy was the nominal editor and publisher at Fawcett, but he also travelled widely and even competed at the shooting events at the 1924 Olympics in Paris, achieving a final rank of 18. When Billy died in 1940, his oldest son Roger became Vice-President of the company.

Captain Marvel

On April 18, 1938, National Allied Publications put out the first issue of Action Comics (dated June). It featured on its cover the first appearance of Superman, smashing a car against a cliff. Its first 13 pages introduced Superman. By the late 1950s Action Comics became focused exclusively on Superman stories, continuing to be published to this day, save for two brief hiatuses in 1986 and 1993 due to the death of Superman. Last March, DC Comics announced it would re-launch all 52 of their titles (calling them “The New 52”) including Action Comics in September. A new Action Comics #1 came out on September 8th, written by Grant Morrison (who also wrote the acclaimed All-Star Superman and penciled by Rags Morales).

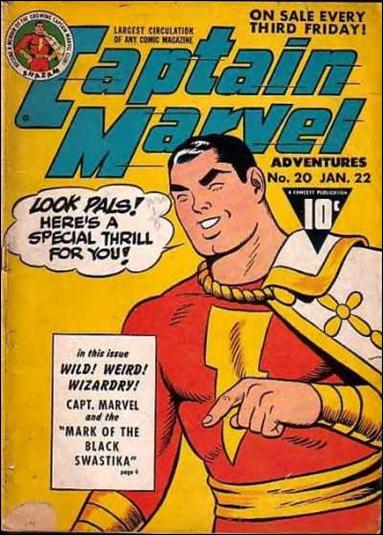

Fawcett founded a comics division in 1939. They brought in Bill Parker who created some comic heroes including a team of six superheroes having a super power given to them by a god or mythic figure. Fawcett Comics’ executive director Ralph Daigh told him to combine the six into one and brought in C.C. Beck to draw the character.

Fawcett founded a comics division in 1939. They brought in Bill Parker who created some comic heroes including a team of six superheroes having a super power given to them by a god or mythic figure. Fawcett Comics’ executive director Ralph Daigh told him to combine the six into one and brought in C.C. Beck to draw the character.

The character was originally called “Captain Thunder,” but was eventually changed to “Captain Marvel.”

Captain Marvel first appeared in Fawcett Comics’ first official book off the press, Whiz Comics #2 in late 1939 and dated February 1940. The #2 comes from the publication of Flash Comics #1 and Thrill Comics #1 that were put out for trademark reasons and were not sold (known as ashcan copies).

The cover is similar to Action Comics #1, with Captain Marvel throwing a car full of bad guys against a brick wall. Also like Action Comics #1, the first story was an introduction to Captain Marvel and his fight against his arch-enemy Dr Silvanus in a plot to end radio. The wizard Shazam gave mild-mannered kid Billy Batsen incredible powers, and when Batsen yells “Shazam,” a lightning bolt strikes him and turns him into the adult Captain Marvel. Batsen held down a job as a reporter for the radio station WHIZ, where he would tell the stories of Captain Marvel on-air.

“Shazam” is an acronym for the six figures of myth that give Billy Batsen his powers – Solomon, Hercules, Atlas, Zeus, Achilles and Mercury. It entered American slang, though it’s probably better known through Gomer Pyle’s use of the term on The Andy Griffith Show and Gomer Pyle U.S.M.C.

Whiz Comics was an instant success. Its first issue sold 500,000 copies (by comparison, Action Comics #1 had a print run of 200,000). Fawcett expanded its monthly comic line in March 1940 with Master Comics which featured Captain Marvel Jr., who’s real name was Freddy Freeman. Freeman became Captain Marvel Jr. after being saved by Captain Marvel from the hands of Hitler’s superhero Captain Nazi. After being knocked unconscious by the Nazis, Batsen passed some of his powers along to Freeman. Another Fawcett title, Wow Comics, featured Captain Marvel’s sister Mary Marvel. Mary Batsen was Billy’s twin sister and was given Shazam’s powers.

In 1941, Republic Pictures made a 12-part serial called The Adventures of Captain Marvel. Tom Tyler, who played The Phantom in another Republic serial, played Captain Marvel and Frank Coughlin Jr. played Billy Batsen. That same year, Captain Marvel got his own series, Captain Marvel Adventures. By 1944, it was selling bi-weekly at 1.3 million copies per issue. Whiz Comics continued to be an anthology book featuring Captain Marvel and fleshing out supporting characters and villains.

Bill Parker was conscripted into World War II, and primary scriptwriting duties went to Otto Binder in 1941. That same year, Marc Swayze was hired to illustrate Captain Marvel stories, but he also contributed many scripts for Captain Marvel Adventures.

Copyright

National Comics Publications held the rights to Superman and sued several companies that made knock-offs of their property. In 1939, they filed suit against Fox Feature Syndicate saying their hero Wonder Man (created by Wil Eisner was too similar to Superman. They sent a cease-and-desist letter to Fawcett in June 1941).

Fawcett decided to fight their claim that Captain Marvel was a copy of Superman. They argued that while Captain Marvel was similar to Superman (having powers of super-strength, super-speed, invulnerability, a skin-tight costume with a cape and a news reporter alter-ego), the differences made the character unique. Captain Marvel’s alter ego was a child and his powers were magic based. A federal judge found that Captain Marvel was an illegal copy of Superman, but that National Comics didn’t hold the copyright to Superman because it had failed to copyright several Superman comic strips.

On appeal in 1952, the judge found that National Comics’ copyright for Superman was valid and that Captain Marvel was an infringement on that copyright.

Mad magazine parodied the legal dispute in their 4th issue with the story ‘Superduperman’. Because of the dispute, Captain Marvel and Superman have battled each other a few times since DC bought the rights to the character.

Comic books, especially those about superheroes had declined in circulation since World War II. The comic reading public gravitated towards anthology books of genre stories like westerns, romance, science fiction and horror stories. Fawcett had moved in this direction too, with titles like Strange Suspense Stories, This Magazine Is Haunted, Lash Larue and many others. Fawcett ended Whiz Comics and all of its superhero titles in June 1953 and paid National Comics Publications $400,000 as a settlement of the suit.

Fawcett Comics closed entirely in 1954, selling off its surviving titles to Charleton Comics. Marc Swayze moved to Charleton as well. C.C. Beck found work as a commercial illustrator. Otto Binder moved to National Periodical Publications (the new name of National Comics Publications. The company would be renamed DC Comics in 1977). While there, Binder created the Legion of Super-Heroes and Supergirl in 1958.

L. Miller and Son, who printed black-and-white Captain Marvel reprints in England adapted Captain Marvel into Marvelman (which has its own long history of copyright battles). DC Comics began licensing the character in 1972 and gained full rights to the character in 1991. C.C. Beck was brought back to Captain Marvel when his series, Shazam! Comics was started by DC. In the first issue, Otto Binder finds Billy Batsen and is astonished that after 20 years he is still a kid. Beck left the title after 10 issues due to creative differences.

Marvel Comics had trademarked a character of the same name in 1967 for its Marvel Super-Heroes series. As a result, DC isn’t allowed to publish books with the Captain Marvel name, or promote series with the character (hence Shazam! Comics).

Paperback Revolution

In 1945, Fawcett agreed to distribute paperbacks of the New American Library imprints Signet and Mentor, provided they didn’t compete and publish their own paperback reprints. By 1949, Roscoe Fawcett wanted to establish an imprint for paperbacks and felt that publishing first-run paperbacks wouldn’t violate the contract. He published The Best of True Magazine and What Today’s World Should Know About Marriage and Sex, two paperback anthologies of stories from Fawcett’s magazines not yet published in books. When those two books went through the loophole, Fawcett started Gold Medal Books to print first-run paperbacks, a first in the publishing industry.

Fawcett had a stable of artists for their magazines that would illustrate the covers of paperback originals. They and their imitators would hire artists away from the struggling pulp magazines to illustrate their covers and many of them would hire writers away from them too.

Pulp magazines were declining in circulation during the 1950s thanks to competition from television. When their talent pool jumped to the first-run paperback, their income fell even further and by the end of the decade, most of them had closed.

Some pulps, like the long-running Argosy and Adventure remade themselves into ‘men’s adventure’ magazines that featured male heroes rescuing a damsel in distress, supposedly true stories of daring adventure, pinup pictures and advice; basically glossier versions of what they were before. They also closed by the end of the 1960s.

In 1952, Ian Ballantine offered a deal with Houghton Mifflin, where authors had their books printed hardcover editions while a new imprint, Ballantine books, would print paperbacks. For its first book, Cameron Hawley’s Executive Suite, Ballantine sold 21 times as many copies as Houghton Mifflin sold hardbacks. Ballantine eventually became known for publishing science fiction and fantasy. Ray Bradbury’s classic Fahrenheit 451 was first published as a Ballantine Paperback.

Fawcett’s magazines were sold to CBS in 1977, which continued to publish Mechanix Illustrated through a few incarnations until it stopped in 2001. Fawcett’s paperback imprints were sold to Ballantine Books (which by this point had become a division of Random House) in 1982.

Captain Billy was an adventurous spirit. He also had a sense of fun about what he did. These traits carried over into Captain Billy’s Whiz Bang and Captain Marvel. Part of the reason why the character did so well is because of the humor of the series and the ordinariness of Billy Batsen, in contrast to the tragic backstories of superheroes like Superman and Batman.