Reviled at the time of its release, and now considered a cinema classic, Blade Runner still attracts attention. Tina Bexson has an audience with the androids

“I’ve seen things that you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched c-beams glitter in the dark near Tanhauser Gate. All those… moments will be lost… in time. Like… tears… in rain. Time… to die”.

It’s the climactic speech of Ridley Scott’s sci-fi classic, where Roy Batty, the dying replicant leader played by Dutch actor Rutger Hauer, enlightens ‘blade runner’ Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) of the more enriched lives, and physical and emotional superiority, of Nexus 6 replicants. And it’s proceeded by an act that eloquently depicts the ambiguous nature of what it is to be human and not human with Hauer’s ebbing replicant saving the life of his killer by pulling Deckard to safety. Most of all, the scene perfectly sums up the whole point of what has to be the most famous sci-fi film ever made.

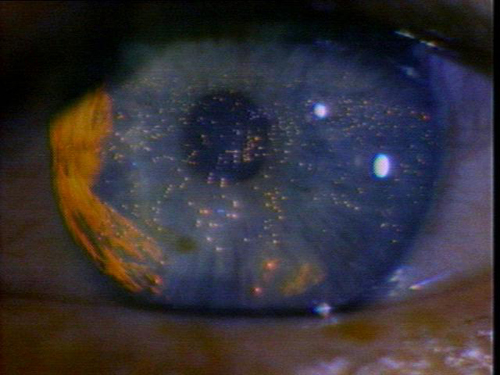

Set in a decrepit 2019 Los Angeles, and based on Philip K Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Blade Runner traces the attempts of cop Deckard to ‘retire’ four genetically-engineered androids who have escaped from an off-world colony to track down their creator and persuade him to expand their pre-determined four-year life span. Its cult status is of course legendary, for it’s a film that had it all, making its longevity quite unique. There’s the exceptional and eclectic mix of sets and special effects creating a Metropolis-style futuristic cityscape that includes the Trumbull-designed Tyrell building, a Mayan pyramid with Art Deco detail; Deckard’s spinner, a quasi-helicopter; and the existing 19th-century Bradbury building in LA where Deckard finally comes face to face with Batty. The visuals are accompanied by a suitably eerie score by Greek composer Vangelis to take us further into Scott’s ‘other world’.

Then there are the offerings of what defines us as human using not extra-terrestrials, but a set of man-made aliens, replicants, played by an unconventional cast. And, as both Hauer and Daryl Hannah (who plays Pris, the ‘pleasure model’ android and Batty’s lover) told me, Blade Runner offers something enigmatic, indecipherable, that makes it intriguing rather than unnecessarily confusing.

“When I read the script it was so great, so different from anything I had ever read before, and still it,” reveals Hannah who still maintains it is her favourite film. “It was almost hard to understand, it was almost like another language because it was so ahead of its time. Before Blade Runner, all futuristic films were quite stark and modern, you know what 50s idea of the future. This was really different, quite complex.”

“Movies where a man fights a robot have been around for many years”, observes Hauer. “Blade Runner’s special irony is that a man fights a robot which is more human than human.”

Hauer’s bleached blonde hair and Nordic looks, gave him an image of ‘perfection’ swiftly grabbing the attention of Scott and producer Michael Deeley, who said that, apart from The Italian Job, it was the best casting experience he has ever had on a picture. “It was wonderful because we had a completely blank page and we went for people who were not comic figures, but who were original looking.” K. Dick was also suitably enchanted: “Seeing Rutger Hauer as Batty just scared me to death because it was exactly as I had pictured Batty, but more so.”

Unsurprisingly Hauer is amongst those calling for a re-release: “The global publicity around Blade Runner has been going on for 20 years. I’m convinced a re-release would make perfect sense now. It would be lucrative. Thinking has changed.”

Thinking has indeed changed since 1982 when it failed quite dramatically at the box office taking only $17million though it cost $28million to make. This initial release (which is the second of Scott’s sci-fi trilogy commencing with Alien and culminating with Legend) included a pathetic voice over and taped on happy ending inserted after the screen tests proved disappointing with audiences baffled by the story line. The Director’s Cut 10 years later brought the film back to what Scott had originally envisioned and got rid of the voice over and silly ending enabling it to receive the critical success it deserved.

Thinking has indeed changed since 1982 when it failed quite dramatically at the box office taking only $17million though it cost $28million to make. This initial release (which is the second of Scott’s sci-fi trilogy commencing with Alien and culminating with Legend) included a pathetic voice over and taped on happy ending inserted after the screen tests proved disappointing with audiences baffled by the story line. The Director’s Cut 10 years later brought the film back to what Scott had originally envisioned and got rid of the voice over and silly ending enabling it to receive the critical success it deserved.

Hauer thinks its commercial failure was to do with it being “cold in sentiment and high in intelligence. Blade Runner raises intelligent questions. Some people don’t like questions”, he adds, when prompted to explain why the American public were so outraged by the film’s depiction of their beloved LA. But those who do like questions continue to take great pleasure in the searching for answers amongst its many layers of meaning. Especially those associated with who is an is not human.

Philip K. Dick, whose work incidentally is increasingly being filmed, what with his short stories Minority Report and Impostor made into feature films [and now The Adjustment Bureau], got the idea of the replicants by reading the diary of an SS officer who said that “the screams of children keep me awake at night”. Scott’s film though depicts replicants as being rather more human than SS officers are. It plays around with their differences and similarities resulting in the ultimate debate relentlessly fuelled by die hard fans on whether Deckard himself is a replicant, used to catch other replicants, and part of the original team of Nexus 6s having had his memories altered after capture. In hindsight and to the increasingly sophisticated cinemagoers, the answer seems pretty obvious. The ‘signs’ are there, they’ll hit you at sometime and in one way or another be it subliminally or smack in the face. The most obvious sign being found in the origami tin foil unicorn left by Gaff at Deckard’s apartment, though it meant nothing until The Director’s Cut when Scott edited in Deckard’s daydream or reverie of a unicorn (using footage from the rushes of Legend) in an earlier scene when Deckard is drunkenly striking keys on his piano. The fact that Gaff makes and leaves the origami unicorn means he must know about Deckard’s ‘daydreams’ and how else could he know unless those ‘dreams’ are memory implants? Perhaps he also wants Deckard to know his life is limited so he will attempt to join Rachel (played by a very restrained Sean Young) on the run. All the other characters, human or not, seem to know he is too – Bryant, Tyrell, and of course Rachel, who cryptically asks Deckard in his apartment: “have you ever taken that test yourself?” referring of course to the Voight-Kampff test which uncovers the emotional and empathic distinctions between replicant and human.

Scott finally settled the issue and confirmed Deckard was a replicant in a 2000 documentary, On the Edge of Blade Runner. It seems he meant it to be that way all along, though the intention could have come about by accident. One of the screenwriter’s (David Peoples) original ending had Deckard meditating on the meaning of humanity in a voice over, but his words were misinterpreted by Scott to mean Deckard was a replicant. Peoples: “The script read: ‘In my own modest way, I was a combat model. Roy Batty was my later brother.’ He was supposed to be realising that, on a human level, they weren’t so different. I think Ridley misinterpreted me, because he started announcing: ‘Deckard’s a replicant! What brilliance!’” Although Hauer said in the documentary that he didn’t perceive Deckard as a replicant, that the question of whether he was, was “kind of a joke”, he told me that he thinks Deckard was a bit of both. “What I understand and think I understand it very well is that Deckard is a human replicant. A man who’s lost his soul to some ‘killerbizz’ and who can easily be manipulated and blackmailed. A man who’s lost mind and matter of what makes him human and a real man.

“Ridley likes playing games with your head. Blade Runner raises questions but doesn’t answer them. I like it too. I think the whole piece is an intelligent mind-fuck.”

Understandably, Hauer quickly related to Ridley’s vision of the future. “Ridley’s vision, I got it, vacuum fit.” That vision is also especially known for its bleakness; it offered an image of dehumanised society as the consequence to technological progress, but Hauer, unlike those many Americans during its first run, seemed to find something almost visionary amongst the negativity.

“Dark is just a word for the black in black and white. To me darkness is what gives us light, and vice versa of course. I find Blade Runner’s visual and musical tones quite exotic, even romantic in a few ways as well as a kind of Miles Davis’ Blue… What I found genius is that by depicting the future as being in decay Ridley gives the future a past, and, therefore, a deeper sense of history and reality.”

It’s not surprising he is so thoughtful and fond of a film that clearly became a turning point in his career and made him the unexpected star over the more bankable Harrison Ford. Ford wasn’t a happy man and frequently fell out with the director and other cast members, most notably Sean Young, both on and off the set. But it seems everyone was falling out with each other. Scott in particular was in the firing line (quite literally at one point), and was constantly battling against an overworked crew and cast with Ford being the most vocal, accusing the director of worrying too much about the special effects rather than the actors’ performances. The moneymen were Scott’s biggest headache, with one of the funding companies jumping straight down his neck the moment he went over budget. The increased stresses and strains made Scott a ‘screamer’, a term he gave himself in hindsight.

Still, Hauer is sanguine, somehow managing to maintain a positive if slightly over-romantic take on the troubles that surrounded him at the time. “Tension, problems, they all helped create what ended up as my screen work. The distance between what is real and not, is very clear to me.”

In fact, he got on very well with Scott, as did Daryl Hannah whose suggestions Scott readily took on board. “Blade Runner and Dancing at the Blue Iguana are sandwich ends for me, because they are two films that I feel satisfied me as to what I always wanted to do as an actress”, she explains. “They are the only two roles that I got to use myself in the way I wanted to, the only ones where I got to disappear in to a role and be creatively involved. Blade Runner wasn’t an improvised film, but I really got to be involved in the creation of Pris.”

Naturally lithe and athletic, Hannah decided she could add something extra to Pris’ physical attributes. “The fight scene with Deckard originally took place in a gymnasium. Basically it was just me bashing around with weights and hanging from rings, kicking him and stuff, and dragging him into exercise machines. The idea of the cartwheels wasn’t in the script but I said to Ridley ‘I can do lot of gymnastics’, and then I did some in the office for him during my audition and I did it again for him during my screen test. He then took out the gymnasium but kept the gymnastics.

“And Pris was a wonderful character to play because I could get really lost in her, even just on the most superficial level. I’d go to work everyday and no one would even say hello to me because no-one would recognise me. Then I’d get into the costume and every one would go ‘good morning Daryl’ because I had transformed into someone else. And I loved that. That’s what I worked for. The fact that she wasn’t even a human being, it was really cool to play with that.”

Hauer’s input was of course slightly more cerebral. Shortly after Pris’ dramatic and horrific ‘death’ at the hands of Deckard, Batty returns to Sebastian’s apartment to be confronted by her dead body, tongue protruding from her mouth. Batty kisses the corpse and gently teases her tongue back into her mouth with his own. “By pushing Pris’ tongue into her mouth, Batty buries her,” explains Hauer who instigated the idea. “It’s a way to make her presentable. He waxes Pris up. Makes her look decent again.”

Hauer’s input was of course slightly more cerebral. Shortly after Pris’ dramatic and horrific ‘death’ at the hands of Deckard, Batty returns to Sebastian’s apartment to be confronted by her dead body, tongue protruding from her mouth. Batty kisses the corpse and gently teases her tongue back into her mouth with his own. “By pushing Pris’ tongue into her mouth, Batty buries her,” explains Hauer who instigated the idea. “It’s a way to make her presentable. He waxes Pris up. Makes her look decent again.”

The subsequent fight scene between Batty and Deckard was storyboarded to a kind of Bruce Lee showdown. Hauer insisted that he wasn’t built like a martial artist and suggested they perform more of a chase, a bizarre dance that reflected the replicant’s final physical and mental state, but one that was over in a flash. “After having had four Nexus 6 replicants die in various big stunty ways of greatness, and it being the end of the film, I felt it better to go back to the truth of death. With batteries running out of steam, the ending would be short and simple.” But Hauer had a further and much more memorable input, and for this we need to go back to Batty’s famous last lines spoken on the rooftops of the Bradbury building. These were unexpectedly ad-libbed by Hauer on the day of shooting.

“The speech – as written – for the ‘end’ was thick and very high-tech. I kept the expressions that still had some space around them and added ‘All those moments…’

“I tend to digest the ‘character’, as far as that goes, and chew the lines, tasting them like some sort of food, see how they feel. In the process I drop unnecessary words. With fewer words they all become slightly more pregnant with possible meaning. But they travel the airwaves in good speed, just like special moments. They are not created. They pass through by accident. But it all depends on the director’s willingness to go there.”

Umm. It could be interesting to see whether actor and director ever work together again during their current lifetimes.

Futurefacts

- Early drafts of the script were called Android, Mechanismo and Dangerous Days. The name Blade Runner came from a William Burroughs book, to which Scott bought the title rights for $5,000.

- Another early draft ended with Deckard taking Rachel to safety out of the city – and then shooting her!

- Dustin Hoffman at one stage wanted the role of Deckard.

- The original budget was $5.5million – it ended up costing over five times that.

- To make the industrial cityscape at the beginning of the film, metal cutouts of oil refineries were lit with seven miles of fibre-optics.

- The Warner Bros New York street backlot, redressed for the exterior scenes, was nicknamed ‘Ridleyville’.

- A UK newspaper interview with Scott, where he unfavourably compared American crews with British ones, did the rounds on the set, prompting the US crew to wear t-shirts saying ‘Yes guv’nor… MY ASS!’

- Scott was actually fired at one point for going over-budget, but was still able to complete the film because nobody else was capable of doing it.

- When he was told he had to record a voiceover for the original cut, Harrison Ford deliberately put no inflection into it, thinking this would make it unusable. He was wrong…

- The tagged-on ending of the original cut came from Stanley Kubrick’s personal collection of outtakes from The Shining.

This article originally appeared in Hotdog magazine in July 2002. Many thanks to Tina Bexson for permission to republish.