Reviewed by Jacob Knowles-Smith

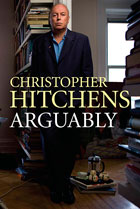

The critic, wrote H.L. Mencken in his Prejudices, “makes the work of art live for the spectator; he makes the spectator live for the work of art”. If we take this as a fair and desirable definition of a critic; which, Mencken continues, results in “understanding, appreciation, [and] intelligent enjoyment”; then in Arguably, his latest collection of essays, Christopher Hitchens measures up to the requirements and succeeds in producing those reactions through his limpid and erudite body of work. Mencken didn’t mention fulminous disagreement or wholehearted approbation – surprisingly, given his record – but one is almost certain encounter these reactions whenever Hitchens comes up in conversation, be it across the press or amongst interested friends. Suspicion should probably be meted equally to those whom describe Hitchens as the world’s greatest author and, conversely, try to dismiss him as a glib pseudo-intellectual. That being said, he simply is, even solely on the basis of Arguably, one of our greatest prose stylists, and is, maddeningly for some, capable of dismissing entire schools of thought and opinion, authors and politicians with a pen stroke of that prose.

The critic, wrote H.L. Mencken in his Prejudices, “makes the work of art live for the spectator; he makes the spectator live for the work of art”. If we take this as a fair and desirable definition of a critic; which, Mencken continues, results in “understanding, appreciation, [and] intelligent enjoyment”; then in Arguably, his latest collection of essays, Christopher Hitchens measures up to the requirements and succeeds in producing those reactions through his limpid and erudite body of work. Mencken didn’t mention fulminous disagreement or wholehearted approbation – surprisingly, given his record – but one is almost certain encounter these reactions whenever Hitchens comes up in conversation, be it across the press or amongst interested friends. Suspicion should probably be meted equally to those whom describe Hitchens as the world’s greatest author and, conversely, try to dismiss him as a glib pseudo-intellectual. That being said, he simply is, even solely on the basis of Arguably, one of our greatest prose stylists, and is, maddeningly for some, capable of dismissing entire schools of thought and opinion, authors and politicians with a pen stroke of that prose.

You need look no further than first section, of six, of the book to appreciate this; of John Updike’s prose in his book Terrorist: “Could anything be more hip and up-to-the-minute?” or “This is a fair attempt to push all the clichés about Irish-Americans into one brief statement”. Examples such as these demonstrate that, though their friendship may have dissolved entirely, Hitchens’s writing still flirts with the influence of Gore Vidal, who was – is? – also capable of this type of constructive literary bitchiness (and also doesn’t escape criticism in this volume).

Arguably is a stout volume crammed with over one hundred pieces for greedy readers in the main taken from The Atlantic, Slate and Vanity Fair. Just under half the pieces are book reviews, mainly from The Atlantic, and these are the essays which elevate Hitchens from a social commentator or pundit – though usually incorporating these two aspects at the same time – to a critic. Indeed, if it had not been for 9/11 he might, as stated in a 2006 profile in the New Yorker, have left politics behind – excepting that his book reviews are of an holistic nature and go far deeper than the text under discussion; see the review of a book about the Founding Fathers and faith which he uses as a shield against the ‘theocratic fascism’ that threatens America today – and not meaning just the Islamic variety.

Obviously matters of religion are central to Hitchens’s body of work but it may be of interest to some, perhaps those wounded Christians who sent him congratulatory letters when he was diagnosed with oesophageal cancer, that there are no outright critiques of religion in this collection. However, there are those that appear in more subtle forms in keen reportages from Iran, Iraqi Kurdistan and Afghanistan, among others, that describe both the oppression of those countries’ people by such outfits as the Taliban and heartening – not patronising – accounts of their desire for change, as we have seen in recent months. (We are also reminded that Saddam Hussein did at least one positive thing during his reign: “By subjecting the Kurds to genocide he gave them a solidarity they had not known before” and thus gave them the impetus to create one of the most liberal societies in the Middle East.) In an essay on Benjamin Franklin Hitchens also gets to employ another of his favourite themes, the deism of the Founding Fathers, and a favourite – for good reason – line, of Franklin’s, about religion: “Created sick, and then commanded to be well”. This is not to say that Hitchens’s writing is repetitive but that when he thinks a point is worth pressing he isn’t afraid to do so. In this case he is especially right to, when considering, as he highlights, that even the great Mark Twain couldn’t see the satire in Franklin’s maxims.

All of the things that have come to be associated with Hitchens are present in this book from Marx and Orwell to Larkin and alcohol, but the most ‘controversial’ piece in the book is entitled, almost as if it has a label reading ‘Inflammable’ attached, ‘Why Women Aren’t Funny’. It is amazing that this little feuilleton written for Vanity Fair attracted so much attention because Hitchens explicitly states that he doesn’t mean that there are no great women comedians but that women do not have the same need as men to be funny in the first place and, secondly, if you don’t think there’s even a hint of irony in it or you can’t shrug it off – then you aren’t funny (darling).

Articles of this nature, though, could give some readers pause to question why Hitchens writes fairly diversionary pieces like this one for Vanity Fair, to which one could add that surely no one should be serious all the time. But why Vanity Fair? A fine publication in many respects but, if you were to look at their website or a random issue, it seems jarring that Hitchens writes for a magazine still so eager to support the Kennedy dynasty and the myth of Camelot – especially considering that, of their legacy, he has this to say: “The reputation of the Kennedy racket is now dependent on a sobbing effort of will: an applauding chorus demanding that the flickering Tinkerbell not be allowed to expire”.

The result of this trade-off, however, is that he is able to write essays that might not otherwise reach such large audiences, such as most of the ‘Postcard’ pieces mentioned above and a tour de force essay in praise of the King James’s Bible and its influence on the vernacular – but only as a stepping stone and liberating force along the progress of mankind towards permanently throwing off the shadow of Rome, and that its abandonment by the Church of England goes to show that religion is a man-made construct “with inky human fingerprints” smeared over its divine body.

The essays in this collection are meant to enrage those who disagree with Hitchens and delight those who find his arguments convincing; but he never asks blind fealty of us – the title of the book gives it all away – and, as he remarks of a Lincoln scholar, he treats us like grownups, with minds of our own. Decades will pass before the permanence of the Hitch’s (if you’ll forgive one use of the overtly familiar colloquialism) work is decided, but if this is his last book, as he fondly quotes of Benjamin Franklin, “litera script manet”. The written word shall remain.