Reviewed by Greg Houle

Long relegated to history’s vast nether regions of obscurity, the twentieth president of the United States, James A. Garfield is best known for two things: he was the last of the American presidents to be born in a log cabin (in Ohio in 1831), and he was the second American president to be killed by an assassin’s bullet while in office (the first being Abraham Lincoln, sixteen years earlier in 1865).

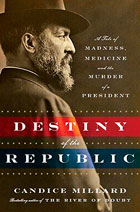

Candice Millard does her best to lift this once highly regarded, entirely self-made paragon of late-19th-century American politics out of anonymity in her new book Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine and the Murder of a President. Millard traces Garfield’s rise as a poor yet precocious child whose father died before his second birthday to his reluctant ascension to Republican presidential nominee and victor of the election of 1880.

“I have never had the Presidential fever; not even for a day,” Garfield said at the time, but in a day when the Republican Party was rife with conflict between the old guard “stalwarts” who believed in the patronage system of rewarding your friends and punishing your enemies, and reform-minded “half-breeds” who favored a government and civil service based on merit, Garfield did not back down from what he saw as his noble duty for his nation.

Solidly behind the “half-breeds” Garfield appointed his former rival and fellow reformer James Blain as his Secretary of State (after he made Blain promise him that he would never again run for president, a promise that Blain, ultimately, broke) and aimed to take Washington by storm and shake up the stagnant and corrupt political system that had washed over the government of late-nineteenth-century America.

While much of the United States was behind Garfield’s reformist agenda, fate unfortunately was not. Less than four months after he assumed the presidency Garfield was shot, at close range, by the fantastically deranged eccentric Charles Guiteau in a Washington, DC train station. Less than three months later Garfield was dead.

Millard, who expertly sets the stage leading up to Garfield’s assassination on July 2, 1881 by introducing her readers to a cast of vivid characters – from the famed and dogged inventor Alexander Graham Bell, to the flamboyant stalwart Republican senator Roscoe Conklin and his toady Chester Arthur (who also happened to be Garfield’s Vice President thanks to a compromise that the stalwarts and half-breeds entered into at the Republican convention), to Lucretia Garfield, the president’s shy yet keenly intelligent wife who Garfield had grown to adore over the years. Yet none of Millard’s characters are as remarkable as Charles Guiteau.

Truth, as they say, is stranger than fiction and Millard seems to relish her opportunity to write about a subject who, if created for a novel, would seem completely unbelievable. After an odd childhood Guiteau attempted to gain admission to the University of Michigan but when he couldn’t pass the entrance exam he instead joined the Oneida utopian society in upstate New York, famed mostly for its acceptance of free love and the fact that its members included two presidential assassins (the other being Leon Czolgosz who killed President William McKinley in Buffalo, New York in 1901).

Despite its free love mentality, the women of Oneida did not warm to Guiteau (in fact, as Millard notes, they took to calling him Charles “Gitout”) and after five years in utopia he left and later filed a lawsuit against Oneida leader John Noyes. After floating around New York and Chicago, Guiteau, who was an expert at sneaking out of hotels without paying his bill and “borrowing” money from distant relatives who he never intended to repay, somehow obtained a law license and began practicing, first in Chicago and later in New York. Never very successful, he regularly enraged his clients by making nonsensical arguments in court that had little to do with their cases.

After abandoning the law, Guiteau dabbled in theology briefly before finding his true calling around the stalwart Republican fringes. This is where Guiteau is at his most fascinating and where Millard shines at capturing his chilling persona. It was during the 1880 presidential campaign that Guiteau convinced himself (and likely nobody else) that he had helped to elect Garfield president by delivering an uninspiring (and little-heard) pro-Garfield speech one time in New York City. It was also during the campaign that Guiteau struck up a one-sided “friendship” with the vice presidential nominee Chester Arthur and other members of the Republican Party, writing largely unanswered letters to them – including Garfield – that took a familiar tone as if he had been friends with them for years.

Once Garfield was elected, Guiteau was convinced that he would be given the ambassadorship to Vienna as his prize for electing the president (later deciding that he preferred Paris instead). Despite the fact that Guiteau never did anything to legitimately help elect Garfield, and that neither the president nor any member of his inner circle had a clue who Guiteau was, he continued to write chummy letters to Garfield and members of his administration. He even joined the throng of office seekers who flooded the White House (a common practice in the19th-century political landscape) after Garfield took office to make sure that the president was aware of his request.

One day, while visiting the State Department to inquire about when he could finally take up his new post in Paris, Guiteau crossed paths with the new Secretary of State himself. Blain, in no uncertain terms, told Guiteau to get lost and abruptly walked away. Crestfallen yet undeterred, Guiteau decided that he had to warn the new president about his Secretary of State who clearly wasn’t aware of how important Guiteau had been to Garfield. But when his warnings went unanswered, Guiteau concluded that the problem ultimately rested with Garfield himself and, with the full backing of God – whom, by this point, Guiteau believed wanted him to kill Garfield – his task was set.

The assassination itself was a relatively simple task in the days before presidents had a protection detail and walked around openly in public places. Guiteau shot the president in the middle of a crowded train station minutes before Garfield was scheduled to board a train to the seacoast of New Jersey and he was apprehended moments later by police.

But what Guiteau thought was his crowning achievement – indeed the very work of God – was actually just the beginning of the end for Garfield and an American public shocked at the news of their mortally wounded leader. Millard then enters the next phase of this tragedy, describing in vivid detail how Garfield, ever cheerful even while enduring extreme pain and facing death, had his recovery thwarted by the antiquated medical practices of a particularly arrogant physician.

While the assassination of James Garfield has largely been lost to the passage of time, Candice Millard’s page-turning new book has brought it back to life in a remarkable way. Adeptly weaving together the stories of fascinating characters to create movie-like scenery, Millard reintroduces us to this truly American tragedy.

Greg Houle is a freelance writer who lives in New York City. Find out more at www.greghoule.com