Set against the backdrop of South America’s poorest economy, Peter Mountford’s first novel is a smart read on the human side of economic, political and ethical dramas. For the author it was also a long road to publication, as Dan Coxon learns. Portrait by Jennifer Mountford

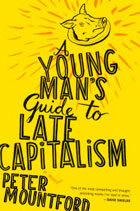

In a literary landscape dominated by celebrity memoirs and vampire soft porn, Peter Mountford’s debut novel, A Young Man’s Guide To Late Capitalism, stands out like a shining nugget of gold. Telling the story of equities analyst Gabriel de Boya as he collects information on Bolivia for an unscrupulous hedge fund, it’s a novel that feels both steeped in tradition and undeniably of its time. As Gabriel wrangles with his conscience and falls in love, Mountford uses his plight to comment on the political situation in South America, the financial bubble of 2005 just as it was about to burst, and the ethical implications of our Western culture of greed.

In a literary landscape dominated by celebrity memoirs and vampire soft porn, Peter Mountford’s debut novel, A Young Man’s Guide To Late Capitalism, stands out like a shining nugget of gold. Telling the story of equities analyst Gabriel de Boya as he collects information on Bolivia for an unscrupulous hedge fund, it’s a novel that feels both steeped in tradition and undeniably of its time. As Gabriel wrangles with his conscience and falls in love, Mountford uses his plight to comment on the political situation in South America, the financial bubble of 2005 just as it was about to burst, and the ethical implications of our Western culture of greed.

It’s also a fantastically good read, and it’s little wonder that the literary world has taken note of Mountford’s achievement. Marrying thriller and romance aspects with unashamed political and financial commentary, A Young Man’s Guide To Late Capitalism is one of the most exciting novels to have come out of the current financial crisis to date–and it’s all the more remarkable for being a debut. Peter Mountford currently lives in Seattle, where he is writer-in-residence for the Seattle Arts and Lectures programme.

When and why did you decide to become a writer?

I started writing by accident. I was 11, I think, and I had this very ornate daydream, but I couldn’t keep track of it all, so I started writing it down. Next thing I knew, I had 50 pages, a novella. When I was 14 I outlined a fictional diary of Vlad Tepes, the medieval prince who was the model for Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Needless to say, I was slightly out of my range with that one and it never came to be.

As an undergraduate, I studied economics and international affairs, and then I went and got a sensible job at a think tank writing about international economics. But I was already a writer, I just didn’t know it. I was sneaking off to write fiction, and the way I was looking at the world, the way I was cultivating and maybe even hoarding interesting life experiences–it was as if I was doing research, and I think I sort of knew it. So, after a couple interesting years being a policy wonk, I quit and started reading Nabokov, Annie Proulx, Milan Kundera–dozens of other great writers. And I started writing three to four hours a day, seven days a week. I haven’t stopped.

Now, mind you, that was 2002 and my ‘debut’ novel was published in 2011.

So what was your journey to publication like during that time?

After embarking on the writing life with lots of youthful vim and vigour in 2002, I began to encounter what’s known, in the business, as the real world. And it was humbling, if not to say crushing. I wrote huge volumes of fiction and got lavished with rejection. My first acceptance for a short story came in 2006, when I was 30 years old. On the plus side, it was an acceptance to the anthology Best New American Voices 2008, but still. By that point I’d collected about a thousand rejections (I keep them all). I’d written and abandoned two-and-a-half novels, and 20-some stories–at least a thousand pages of fiction that will never see the light of day.

In the summer of 2005, my writing turned a corner. I remember it vividly. I was in the middle of the MFA program at the University of Washington and I went to Ecuador for a few weeks, feeling very dejected. The first year at the UW had been a deep low-point. I got savaged with rejection and some very demoralizing critiques. It really broke me down. I began to realise how much higher I needed to aim, how much better I needed to be. At the end of that year I had a very revelatory class with David Shields, who said something to the effect of: ‘Do you really just want to be this dutiful craftsman, creating these quaint stories that are totally antique, totally separated from the world we actually inhabit?’ He said he couldn’t stand to even read that stuff, and I had to admit that I felt the same way.

That summer, Shields got me reading J.M. Coetzee. I went to Ecuador and wrote and wrote and wrote and read and read and read. And when I came back, I was a very different kind of writer and it was obvious, immediately. Within a year, I’d started winning some awards and fellowships and grants. I started publishing in some well-regarded literary journals. In fact, most of what I’ve written since then has been published.

A Young Man’s Guide… reminded me strongly of Graham Greene, specifically the combination of exotic setting, intrigue, and an underlying discussion of everyday morality. Did Greene influence you at all?

Yes, Graham Greene absolutely was a huge influence. In many ways, I more or less aspire to write like he did–both the so-called diversions and the weirder stuff. He was obsessed with God, seemed incapable of not writing about God. I think I’m similarly obsessed with money, how it operates in our planet and in our minds–I set out to write a story about my granny and I end up with a story about money. Other writers I adore include Deborah Eisenberg, Milan Kundera, J.M. Coetzee. Nabokov. And scores of others, of course. The list could go on for days. I’m reading Tom Rachman’s The Imperfectionists right now and it’s tremendous.

Money is one of those topics that great literature often deals with (like love, or religion) but it seems that modern writers are sometimes afraid to address it, or they wilfully avoid it. Why do you think that is? Do you think it’s a topic that should be addressed more often?

Money is one of those topics that great literature often deals with (like love, or religion) but it seems that modern writers are sometimes afraid to address it, or they wilfully avoid it. Why do you think that is? Do you think it’s a topic that should be addressed more often?

I’ve been thinking a lot about this, recently. It seems that literary-minded people have quietly agreed that finance is somehow not central to the zeitgeist. Money is a deeply taboo subject, obviously, and all the more so among people who consider themselves to be artists. Finance and economics are complicated and often poorly understood, also, and they’re not thought of as sexy. A lot of writers I know are proudly dismissive of economics–they paint it boring–it’s either viewed as nerdy, in the unattractive way, or it’s associated with these cartoonish preppy monsters.

That is nonsense. A cursory glance at our recent history reveals that economics and money are not just the engines of our era, not just what defines virtually everything about our time, but they’re also spectacularly dramatic. It’s not an abstract subject. It’s not just a guy with a calculator. It’s very emotional and makes and breaks the lives of–well, everyone. So, yes, I think it’s a topic that should be addressed more often in literature.

The foreign location feels like a big part of A Young Man’s Guide… too; it’s hard to imagine it being set anywhere else. How early did you settle on Bolivia as your setting? Why that country in particular, and South America in general?

I’ve travelled a lot and most of my writing therefore concerns people living in or visiting foreign countries. It’s not a conscious thing, but I suppose I think that when you’re away from your comfort-zone, your home, you have a slightly heightened perception of things, and it casts your own community, your circumstances, in a radically new light, so it can be an awakening. I like having that space as a kind of foundation for a story. That change in perception is all the more true if the place is extremely different, like Bolivia, rather than, say, England.

Bolivia’s also the poorest country in South America, and it’s a bit intense, a bit too hardcore for most people. Not a big tourist destination. So I liked that. And it’s gorgeous, like you’re on the moon–the moon with shantytowns.

And, finally, and maybe most importantly, Bolivia’s history is a near perfect example for the overall experience of countries that were colonized and brutalized by the Europeans. Their history is heartbreaking. It’s occasionally bizarre beyond belief, too–they lost their coastline in a war with Chile over bat guano, which Bolivia wanted to tax (it contains a useful ingredient in gunpowder). There are countless other surreal milestones, like when someone traded a vast swath of oil-rich jungle with Brazil for a nice white stallion. But beneath it all there’s a harrowing history of Northern-hemisphere-dwelling people, mostly Spanish–although the US certainly did its part during the Cold War, in particular–siphoning natural resources from the land without properly compensating the Bolivian people. In Bolivia this aspect of their history it’s referred to ruefully as ‘El Saqueo’–the sacking.

Having spent so long writing about Bolivia (and talking about it in interviews!) do you feel a stronger bond with the country than you used to? How did writing about it change your relationship with it?

When I started writing the book, I was very interested in Bolivia, and I thought its history was gorgeously bizarre and also very apt, a kind of perfect model for the corrosive long-term effects of centuries of colonial pillaging. Now, I love the country and feel a very personal connection to its people. I have a Google alert on Bolivia and so I now read the news about the country daily. Also, I’ve been very heartened by the responses of Bolivians who’ve read the book, because it’s not the most flattering portrait of the country–but I’ve been contacted by a number of Bolivians who told me that they felt I’d captured La Paz perfectly.

I know you teach creative writing in addition to producing your own work. How do you find that it feeds back into your own writing? Is it an integral part of being a professional writer today?

Richard Ford was in Seattle the other day for an event and an audience member asked him what he liked most about teaching, and he replied, ‘The money.’ So, yeah, it’s an integral part of being a professional writer, especially if you’re not writing bodice-rippers. If you’re writing books that take years to write, the kinds of books that don’t sell very well because they’re ‘difficult,’ then teaching is probably how you pay the rent.

There’s another reply to this question, of course, one that talks about how inspired one gets by one’s students, but that’s nonsense. Or, if someone says it sincerely, they’re probably not much of a writer. I like what David Foster Wallace said about this in a Charlie Rose interview, he said something to the effect of, ‘The first couple years it’s really revelatory, you learn a lot from your students and it’s a very hard experience. Then, once you’ve seen a few thousand undergraduate stories, it becomes just another day job and you no longer learn anything at all from it.’

I like teaching because it gets me out of the house, and it generates some income, and I like the act of talking about writing–that’s why I’m friends with a lot of writers, and when I teach I get paid to have those kinds of conversations. Also, it’s very fun to discover a writer who is fucking amazing and doesn’t know it yet. Some woman, say, who does data entry at a medical supplies company, and I get to inform her that she’s ready to get published, and that she should get in touch with a top-shelf literary agent in New York City at her earliest convenience. That’s fun, but it doesn’t happen that often.

If you were given a time machine that allowed you to go back and tutor your younger self, what advice would you give to the younger you? Or are there any particular skills that you’d tell yourself to work on?

I’d tell myself to aim higher, stylistically, intellectually–in every way. Like so much fiction by beginners, mine felt like the writing of a person who just wasn’t working hard enough, word by word, paragraph by paragraph, chapter by chapter. If a sentence isn’t doing several jobs at once, it’s probably dead weight. I’ve heard that there’s only one rule with writing: never be boring. I like that, the writing needs to be fucking riveting, one way or another. I’d add that authenticity is very important–if you’re not writing about something that really matters to you, deeply matters to you, it’s probably going to feel a little trite.