Spike enters the strange world of body modification

[Award Winning Tattoo Designs – The Biggest And Best Collection Of Tattoos.]

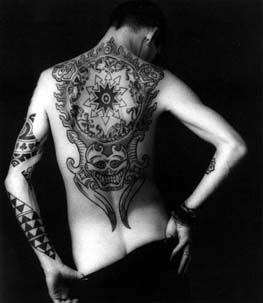

Tattoos. Piercing. Dreadlocks. Body Art. What is the world coming to?

It would seem if we follow the lead of much of the popular press a minority of degenerates are corrupting our sensibilities, and so we are doomed. However, if you take the time to stop and look a little longer, it seems more likely that we actually want to be corrupted. And this desire is not new. The time when anyone with a tattoo is treated with apprehension is slowly fading away as body art becomes more and more mainstream.

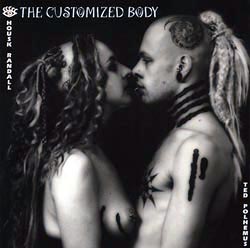

There is currently an interest in utilising the body as a site on which we can extend our creative and psychic desires, and as such has found itself reflected in a growing literature of its own. One such book is Housk Randall and Ted Polhemus’ The Customised Body. As Polhemus and Randall make clear from the start, the impetus for this fashion in changing the body is the influence of ‘traditional peoples’. Other cultures, which have been traditionally termed primitive, have a history of altering their physical appearance for either religious and social purposes.

And it is this that the later-day primitives of our culture are trying to tap into. Thus the piercing or the tattoos of these ‘modern primitives’ are legitimated through the idea that they are some how more pure, honest and true, because they reflect the more positive aspects of these so-called ‘simpler’ societies. Attempts are also made to suggest a lineage for the use of such body art by the examination of early pre-Christian practices in the west. However, though this may provide a precedent for body art, it is more pertinent to question why such practices fell from fashion for several thousand years, and in turn, why they would have any pertinence now.

Much is made in the literature that surrounds this particular subculture about the need for self-expression, and the desire to feel part of a community. The subtext of such an argument is that a certain sector of our society feel that they can not adequately express themselves through the more conventional means of visual expression, be it clothes or art. The notion that other cultures will provide us with a visual language that will release us from this empasse is, however, not new. In art alone it can be traced back through the major canon of western artist, through Jackson Pollock, Picasso, Gauguin, Van Gogh, and back into the depths of the eighteenth century at least. What is new is the transition from the canvas and the gallery, to the body and the street. This phenomena, I feel, must be a result of the late twentieth century, or dare I say it, post-modern, belief in the breakdown of artist as unassailable god. Instead, the artist can be any man, and as a result of the comments of Duchamp and the whole dada movement, art can be anything.

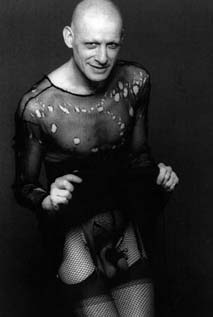

Also written into the unspoken creed of this grouping is heart-felt belief that there is a direct correlation between the increase in the isolation in our post-industrial society and the desire for primitivism. It is almost as if that as God was once usurped by science and money, it too shall necessarily collapse, but his time under the force of this new godless mass who have found belief in some crypto-primitivism and a new hybrid culture. As such fashion, in all its manifestations, is the tool by which these new pioneers of culture seek to bind themselves: through self-expression one finds those who hold similar beliefs, those who have similar aims.

However, there is also an ideological factor to be considered when we consider modes of dress or rituals of display. It can clearly be seen that the members of this ‘fashion’, or as Polhemus describes them, members of a ‘style tribe’, are generally of an underclass which wishes to identify itself. If, then, the disenfranchised and the disheartened give up on conventional codes or symbols they are signalling to the dominant culture, and to those who have not yet made that step to identify themselves, that they are out there on the edge. And more importantly, if they are not happy to be there, as some surely are, they are issuing a rallying call to join them, as there is surely safety in numbers.

The way the people who operate in this cultural space are in actuality, however, very different from the theory. The more you look at this phenomena the more you realise that there is no one answer, but instead we are able to perceive a set of answers that make up a larger question. That question I believe, is along the lines of this: we have a culture, one which is straining at its edges. The more diverse the world becomes, or we perceive it to become, the more it pulls at its seams. The more we question it and pry at its secrets the more the stitches loosen. What we really want to know is, where do we go from here? The answer I think is found in this new interest in primitivism, and especially in the ways in which we can combine it with ideas of the future.