Lesley Dill, 'Rush', 2006-07. Metal foil, organza, and wire; dimensions variable

Lesley Dill’s work begins with language and extends, through many shapes and forms, to the body and the community. Thyrza Nichols Goodeve’s essay ‘Words have Wings that Fly from the Mouths of Others’ (1, see footnotes below) first appeared in the catalogue for Dill’s 2009/2010 retrospective I Heard a Voice. Many thanks to the author and Hunter Museum of American Art for permission to republish

In the end, then, we’re all readers. And the act of reading is an active choice to receive – and also to participate, to imagine, to interpret. It’s a kind of gift we make to writers, in fact – just as much as their writing may seem a kind of gift to us. We choose to let their words in. To let them “flame amazement” in our minds, where they may indeed prove incendiary. – Stephen J. Bottoms (2)

I read on, I skip, I look up, I dip in again. – Roland Barthes (3)

Poesies (Greek): to make or to create.

There is the moving image. There is the sculpture. There is the pull of a ribbon. There is the photograph. There is the sculpture of an open hand, long colored threads attached in bunches to the fingertips, pulled by gravity to the floor. There is the wire that is woven, the photographs that are scratched, the foil that is cut, the obsessive repetitive gestures of the making, the duration and the weeks and months it takes. There is the text, the words, the repletion. The constant push and pull between, and yes, among images and words, reaching beyond the frame. Nothing is ever quite content to rest. Hesitations, requests and suggestions of movement and meaning. Diaphanous spectacles and shifting displays, in the gallery and the museum and elsewhere in live performance and opera. All in motion. All about language. All as visual art.

Lesley Dill has made art in collaboration with the poetry of Emily Dickinson since 1990. Correction, Leslie Dill has made art out of, and with, Dickinson’s language, not her poetry, since 1990. Rarely does she work with an entire poem but instead culls line fragments –

A single screw of flesh is all that pins the soul. (4)

A single screw… is part of a poem that is 20 lines long. But for Dill its power is as a solitary sentence which becomes a kind of cloth, or a ribbon, draped and reprocessed.

Dill drinks in the intelligibility that teases from the tips of comprehension. Her disregard for the literary tradition of the poem as a whole puts her in the same hashish garden where Baudelaire dreamed modernity and Dickinson drew large breaths. The garden without paths where, “in prose and poetry she explored the implications [of language] breaking the law just short of breaking off communication with a reader”. (5) Dill “breaks” or surgically separates lines of poems like slices of skin, recycling and repeating lines, reusing them, a bit like a lyrical, less narrative, Gertrude Stein. Stein may seem like an arbitrary connection but the first chapter of Susan Howe’s landmark book My Emily Dickinson, actually discusses Dickinson and Stein as literary mates, who were “…clearly the most innovative precursors of modernist poetry and prose”. (6)

Of interest for our discussion is Gertrude Stein’s notion of language. For Stein, language was not a vehicle of communication or expression but was a material with volume and mass like clay or paint. Decoration was not what counted, i.e., the razzle dazzle of description or vocabulary, but the way meaning could be built by accretion over time by what she called “repetition as insistence.”

[S]ometime there will be a history of all of them, that sometime all of them will have the last touch of being a history of being, a history of them can give to them, sometime then there will be a history of each of them, of all the ways any one can know them, of the ways each one is inside her or inside him, of all the ways anything of them comes out from them. (7) – Gertrude Stein

Dill’s use of repetition is not formal like Stein’s. It works like a mantra. Dill is a mystic with an interest in Buddhism, Judaism, and the work of the American Transcendentalists. Stein’s method pounds meaning from the rat-tat of simple pronouns, nouns, prepositions signifiers, edited frame by frame. She does not use descriptive language. Meaning is never made by metaphor, but by physical accretion of word by word, amassing like the rings of a redwood tree at is ages from year to year. Repetition builds, insists and history is written. (8)

Stein, the writer, makes from language.

Dickinson, the poet, creates language.

Lesley Dill, the artist, is a creature of language. She grew up in it. She inhabits it. She is and becomes it. But it pushes her to something else. To perform Dickinson’s poems across, in, and, as a range of materials;

walls

voice

lights

sculpture

photograph

live performance

paper

video

textile

installation

opera

This is repetition as insistence across media as well as language.

The Pleasure of the Text

It is the abrasions I impose on the fine surface:

I read on, I skip, I look up, I dip in again. – Roland Barthes. The Pleasure of the Text. (9)

In his book The Pleasure of the Text published in France in 1973, translated into English in 1975, Roland Barthes discusses texts of “pleasure” – plaisir – and texts of “bliss” – jouissance. Dill’s experience of reading the volume of Dickinson’s complete poems, given to her by her mother on her 40th birthday, is clearly jouissance (ecstasy, bliss). Ecstasy is a theme that returns again and again in Dickinson’s poetry, and is in Dill’s experience of reading Dickinson. “I had imagistic epiphanies that almost frightened me they were so strong”. (10) What Dill describes, and re-enacts in her art, are moments of reading, when a writer’s words implode inside and out and through the body in a manner only poets have been able to capture.

Reading is a verb. At its best, it expresses communication and connection of such exquisite recognition and contact that it is love, but not just love, it is being in love, but not just being in love, it is the beloved: mirror, soul, essence giving flight in those words. For Barthes, reading, which is writing, is like a drug; it is why readers are always addicts. This is why Dill returns to Dickinson several times and why it is never a return or a repetition. She is always after the language as transcendent action on and in the body: desire, insight, bristling, burning, ecstatic, implosion, spinning-moment of mind-altering (brain changing) engagement where text and body are pierced, made into one, obliterated, fused.

Dill is about poetry as text, entering the body from page into the body, and then out again into objects. She acts it. Not just in performances but also as a drive, the gesture of affect and meaning, spreading its way like a band of light. Her art is made of delicate materials and ethereal images that breathe through language, taking us elsewhere and roughing us up. The phrases she has read, and that are her material, carve into what cannot be seen, what cannot be touched, what cannot be understood, but are what is felt in a flash (jouissance) –

reading as contact

as gift

as performance

a poem as a Punch, 1999 in the mouth or a Flinch, 2000.

Like Walt Whitman, Dickinson’s partner in time, he says, “Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself, I am large, I contain multitudes”. Dill too, contains multitudes. And contradictions. Her performances are like poetry readings but in them the human body replaces paper, and the poems are repeated as well as written on scrolls that are pulled from mouths and attached to eyelids. Her sculptures are made of paper and materials such as horsehair and wire, yet wire is then woven into poetry for her photographs, Dill treats bodies as a kind of paper, and the process as a form of reading:

I’d paint on people – friends and volunteers – and then I’d photograph them. I am attracted to photography because it literally makes a human being into a human piece of paper. It makes them frontal. It makes for a reading. (12)

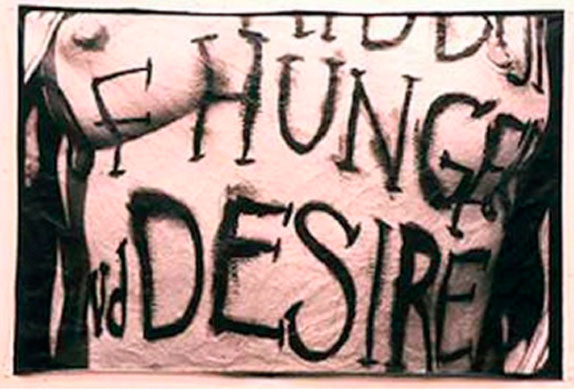

Lesley Dill, 'Hunger and Desire', 1998. Oil, thread, wax on photo; 49 x 77 inches

The Object as Bridge

Fragile Bridge (2005), made out of horsehair and wire, is a visceral piece. (13) The piece hangs on the wall yet one does not feel it as a wall piece. We approach it and feel it. The horsehair droops from the wired text to the floor. It is attached to woven words that stretch in awkward “handwriting” from left to right across the wall. The piece is at once mural, sculpture, poem. As we walk, we read – absorbing both the tactility of the piece, the smell or the olfactory associations we have with horsehair and the images and feelings of the words. We are reading in action – bodies in motion. “reading was a connective tissue,” (14) the fragile bridge of creation and connection Dill had with her father. In the beginning was not the word but the reading of a word that had several personalities in her family. Dill’s mother taught speech at the high school the artist attended, so for Dill, words were not just things that communicated meaning but things that sounded, carried melody, that had their own physicality and skins. A word could be clunky or impatient; a sentence as lyrical and crisp as the sound of snow. From her father, Dill discovered language wore many outfits. What he said was layered and shifted, conflicted, came and went from elsewhere because he read and heard and spoke to the world as a schizophrenic:

but do not tense up. He was beloved, a very kind man…

He knew I understood. He would slant the language towards me. I feel that I grew up in a psychologically bilingual family. For me words existed naturally in duplicate, triplicate and quadruplicate context. There was an inherent meaning, a secret meaning, and a surface meaning. (15)

So for the young Dill, words did not greet the world like dutiful citizens but scratched at the tips of the tongue, drifting and colliding into new territory, making new worlds. Language was not just story or communication but sound and split crystal. It could not only travel along multiple tracks, but breathe and thread itself into material.

And when her mother gave Dill the book of Dickinson’s poetry, reading it completely atomized her world.

Dickinson’s language released something in my unconscious mind. My response was not tied to her content, but to the immediate sense of feeling ‘lined up’ with the experience of her words. I’m interested in the ‘alchemy’ of language, the uncertainty of meaning and the resonance within our bodies when a metaphor clicks.

But also

It’s when you eat something

I felt the words were in my body the words came I felt my life from within. (16)

Words are digested. They become flesh and skin. Words heal and scar. They are the skin. They are what slice it off. We are blood and light. a poem.

Flash

of brilliance

of knowledge

of transcendence

of knowledge

out of body

Dill exteriorized and interior experience of language and returned it to the audience as a fragile bridge she and we walk together through museum, gallery, book, live performance. And “We choose to let their words in. To let them ‘flame amazement’ in our minds, where they may indeed prove incendiary.” (17) And she has been set on fire to create outside of this art arena, this self of hers and ours and Dickinson’s, to a different kind of performance and reading. The kind of reading that becomes a listening, to be read, heard, released and brought back in from.

And your very flesh shall be a great poem. – Walt Whitman (18)

Tongues on Fire

In the year 2000 in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Dill produced an extended community project created from research, listening, singing, writing, and reading, that has had an effect on all of Dill’s work in the ‘00s. The project, called Tongues on Fire was different , quite special and carried its own aura. As Arlene Raven states,

We ponder an explanation of sacred language that Lesley has found while preparing to launch her community project in Winston-Salem. Language itself, as consecration and prayer, is three-dimensional and rooted in the yet unsaid. (19)

Dill was invited to the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art [SECCA] to participate in a residency program sponsored by the museum’s Artists and Community series. Since 1994 this series had brought artists to the Piedmont region of North Carolina to work with the community on collaborative projects. Dill was an interesting choice because her work is generally so private and hermetic. What would an artist who makes such intimate works as White Threaded Poem Girl, 1996, Punch, 1999, or Girl With Crown, 1998, do with a community, especially one as diverse, urban and Southern as Winston-Salem’s? Dill turned to the community and treated it like a collection of poems.

Dill has always referred to herself as a “word collector”. A collector does not read in the traditional sense, but selects and cuts, like a gardener weeding from bushels full of possibilities. In order to collect the words of this community, Dill integrated her skills as a reader of texts into the skill of a listener of people. She visited schools, libraries, churches, bookstores, placing articles in local newspapers, did interviews on the radio, hung posters in neighborhoods. SECCA also set up email and voice mail boxes for the community to leave responses.

Public tongues. Others’ tongues. A community instead of a book. Dill had been mining, for the most part, from the same personal volume of poetry for a decade, poetry from one of the most lauded introverts in American literature. But in 2000 Lesley Dill became an actor out in the world. Her words were not epiphanies driven from her reading poets, but via performance within the language of a community. This was no simple new assignment but a transformation of her work from the infinite interiority of the one (Dill, Dickinson or the poet, the viewer) to the performance of a profoundly public interiority. At each event, Dill worked with the language of intimacy to break down barriers. She shared her visionary experience, turning it into a mode of research, becoming a collector of visions:

It’s the language of visions – be it in dreams or unusual sensory experiences, spontaneous vocalizations, or uncontrolled body movements – that I was interested in investigating in the community of Winston-Salem… (20)

She received 700 visionary statements. Those were not her own, nor of dead poets, but voices – alive.

These stories revealed how complex and how simple this mysticism is. Each shared experience had a context of complication with acceptance of the range of life. It’s neither sweet nor sentimental… it’s not one pure point of understanding. It’s rich – it mirrors life that way. (21)

One particular community in Winston-Salem: the Emmanuel Baptist Church (22) whose Reverend John Menedez, part Apache, part Yoruba was himself a particularly gifted spiritual “seer”, collaborated with Dill. The diminutive New York City female artist-outsider – white, blonde, reserved New England archetype – from a mystical, Buddhist, Episcopalian, Jewish tradition, collected experiences of inexplicable bliss or all-knowingness, and then had an African American choir “that can be traced to slaves of Gullah descent who arrived on the continent from Sierra Leone West Africa, as captives destined to work on the South Carolina rice plantations” (23) transform them into performance, into song. Yes, as the Reverend said to her, “Lesley, we accept you as you are”. They met and through a series of conversations and shared experiences, created the most ecstatic aspect of the collaboration.

A huge and varied amount of work evolved from Tongues on Fire – billboards, spiritual sings woven of the community visions, a documentary film, two publications, including the original 700 vision statements and, in many ways, all subsequent exhibitions, from Tremendous World, 2007, to the opera Divide Light, 2008. (24)

After this community project, pieces such as Rise, 2006-07 [originally created for the exhibition, Tremendous World, 2007], are metaphor for the way performance has become more central to Dill’s work. The lone sculpture or hanging wall piece, or specific line of a poem, is no longer unattached, isolated, standing on the floor on its own, but attached literally, to voices and a public that are trying to take it elsewhere. (25)

As far apart in time and mode as Tongues on Fire, 2000, and Tremendous World, 2007, are – one an entire project, exhibition, and all-encompassing range of media, the other a series of sculptural installations – Dill has spoken about both as crucial aspects in the evolution of the most significant commitment to performance she will make in the ‘00s: her opera Divide Light. Although in content, Divide Light features images, language and works only from Dickinson and Dill, the entire process of making the opera is of course a community project, and a public exhibition in front of an audience. In Divide Light, the private voices of the gallery and the poet, the personal and the hermetic are shifted to a grand operatic display of interiority itself.

In the end, it is the tension in post 2000 exhibition works – performance culled from a community rather than just in front of an audience, or in the gallery, on a page, or from the poet’s private language – that has allowed Dill’s work to become a melody that fills rooms.

Lesley Dill, 'Rise', 2006-07. Laminated fabric hand-dyed cotton paper metal silk organza; dimensions variable

Footnotes:

- Lesley Dill.

- Stephen J. Bottoms, The Act of Reading (and the Fire Next Time), www.readreader.org.

- Roland Barthes, The Pleasure of the Text, translated by Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1975). (38)

- The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, Emily Dickinson #263 edited by Thomas H. Johnson (Boston: Little, Brown & Company. 1960).

- Susan Howe, My Emily Dickinson (Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books. 1985). (11)

- Ibid.

- Gertrude Stein, Negotiating an Hospitable Sublime, The Sublime of Intense Sociability: Emily Dickinson, H.D., and Gertrude Stein. Contributors: Shawn Alfrey (Lewisburg Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press, 2000). (118). From www.questiaschool.com.

- Gertrude Stein, The Making of Americans: Being a History of a Family’s Progress (1906-08).

- Roland Barthes, The Pleasure of the Text. (38).

- Leslie Dill quoted in Tom Patterson’s essay, Opening to Unknown Nourishment: The Singular Trajectory of Lesley Dill; exhibition Tremendous World, Neuberger Museum of Art, 2007.

- You May Laugh but I feel within me suddenly strange voice of god and handles Dont’s thirst and message Of slow memories that disappear Across a fragile bridge (Salvador Espriu)

- Lesley Dill, quoted in exhibit catalog, Lesley Dill, A Ten Year Survey, Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, 2002. (11)

- It is a sister piece to Ann Hamilton’s 1993-1994 Tropos.

- Lesley Dill: “Reading was a connective tissue. With my father, there was reading on a different level. There was reading by inference, by listening. The kind of listening where you hear not just one word, the spoken word, but you hear underneath it and behind it; like tonality that one finds more in Asian languages.” We are all Animals of Language by Ed Robbins, 2007.

- Lesley Dill quoted in Dede Young’s conversation in exhibition catalog Tremendous World, Neuberger Museum of Art, 2007. (21).

- Lesley Dill quoted in Susan Krane’s essay, Read Me Like A Book; exhibition, Lesley Dill: A Ten Year Survey, Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, 2002. (49)

- Stephen J. Bottoms.

- Ibid.

- Arlene Raven, Tell It Slant, in exhibition catalog, Lesley Dill: A Ten Year Survey, Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, 2002. (12)

- Dill in Krane, Lesley Dill. (49)

- Lesley Dill quoted in Singing Forth the Spirit, by Terri Dowell-Dennis in Tongues on Fire, SECCA, 2000.

- Ibid. (7)

- She also worked with 400 high school students in the Governor’s School West program, a special summer institute active since 1963, attended by selected students from all over the country. In 2001-02 her project, Interviews with Contemplative Minds, evolved out of a collaboration with the University of Colorado, the Naropa Institute, and the choral group Ars Nova in Boulder, Colorado.

- Dowell-Dennis in Tongues on Fire. (13)

- Divide Light is an extended and insistently repeatable operatic re-reading of Dickinson and Dill.

- The language embroidered on the banners in Rise are quotes from Tongues on Fire.

I Heard a Voice: The Art of Lesley Dill

Hunter Museum of American Art, Chattanooga, Tennessee

January 17-April 19, 2009