Chris Hall talks about the dark side of capitalism and the deceptions of reality with J.G. Ballard

Walking along Oxford Street the day after I finished reading JG Ballard’s new novel, Super-Cannes, it struck me, literally, the total acceptance of the substrate of violence in consumer societies when it manifests itself. A silent, monolithic crowd hurtled down either side of the road as I walked from Centrepoint to Oxford Circus. I counted the number of times that I was physically forced to move out of the way or get hit head on (five). I counted the number of times I was pranged, bumped or rear-shunted (four). It’s said that London traffic moves at an average speed of 11mph, but pedestrian traffic can’t be far behind. Indeed, it’s not too fanciful to see in these crowds how the car has influenced our spatio-temporal perception. You see overtaking manoeuvres, you see people checking their rear views, as it were, with a glance behind before moving out. There is the same frustration at slow moving traffic: the same parameters of territoriality are in operation.

My shopping trip reminded me of a passage from the book in which Wilder Penrose, the resident psychologist of the business park Eden-Olympia, says “Our latent psychopathy is the last nature reserve, a place of refuge for the endangered mind. Of course, I’m talking about a carefully metered violence, microdoses of madness like the minute traces of strychnine in a nerve tonic.” And that’s just what that experience felt like: small, discrete moments of psychopathy.

It was with this in mind that I spoke to JG Ballard, who’d granted me the last interview on the round of publicity he’d been doing for Super-Cannes with the nationals. Unlike most people who interview Ballard, I wasn’t worried about whether he would be cold and distant or abstract, but simply that there wouldn’t be enough time with the Seer of Shepperton. I was right not to worry about any of those things. His voice has a rhythmic, musical quality, and his laughter is warm and inclusive. He gives the impression of an eccentric school master with, yes, a slightly abstracted air; a patrician whose sentences end with a heavy emphasis. Ballard is clearly used to developing an idea without interruption.

J.G. Ballard

“The main theme of Super-Cannes,” he says, “is that in order to keep us happy and spending more as consumers then capitalism is going to have to tap rather more darker strains in our characters, which is of course what’s been happening for a while. If you look at the way in which the more violent contact sports are marketed – American Football, wrestling, boxing – and of course the most violent entertainment culture of all, the Hollywood film, all these have tapped into the darker side of human nature in order to keep the juices of appetites flowing. That is the risk.”

Or as Wilder Penrose says in Super-Cannes: “A perverse sexual act can liberate the visionary self in even the dullest soul. The consumer society hungers for the deviant and unexpected. What else can drive the bizarre shifts in the entertainment landscape that will keep us ‘buying’? Psychopathy is the only engine powerful enough to light our imaginations, to drive the arts, sciences and industries of the world.”

Ballard makes the simile with politics – “Hitler tapped into all kinds of psychopathic traits in the German people, the race hatred in particular: Jews, Gypsies, non-Germans, all ‘biological inferiors’. These were very potent ideas that are probably carried in all of us from our distant past when it made sense to fear strangers because they were probably trying to steal your cattle, kill you or rape your wife. Hitler tapped those buried layers of psychopathy. It’s an example of what could happen.”

With Super-Cannes we once again have all the cool clarity of a writer who has never flinched from his subject matter for the last 40 years. As our narrator, Paul Sinclair, drives south to the French coast with his doctor wife Jane, towards Eden-Olympia, their new home, “hundreds of blue ovals trembled like damaged retinas in the Provençal sun”. Ballard writes of the flare of swimming pools on the hillside: “Ten thousand years in the future, long after the Côte d’Azur had been abandoned, the first explorers would puzzle over these empty pits, with their eroded frescoes of tritons and stylised fish, inexplicably hauled up the mountainsides like aquatic sundials or the altars of a bizarre religion devised by a race of visionary geometers.” Thus we are in familiar unfamiliar territory, in a world we think we know but which is perhaps meaningful only retroactively.

Once again there is the Ballardian theme of morality reduced to aesthetics, or as Paul Sinclair has it “Civility and polity were designed into Eden-Olympia. By the end of the afternoon all this tolerance and good behaviour left me feeling deeply bored.” Sinclair is in a world in which “A moral calculus that took thousands of years to develop starts to wither from neglect, an adolescent world where you define yourself by the kind of trainers you wear.”

Super-Cannes takes off as a “why-dunnit” when Paul Sinclair learns that he and his wife have been housed in a villa whose previous occupant, David Greenwood, had apparently gone insane and killed seven very senior executives. Sinclair says: “It occurred to me that three of us would sleep together in this large and comfortable bed, until I could persuade David to step out of my mind and disappear for ever down the white staircase of this dreaming villa.” As so often with Ballard’s fiction, a fusion of inner and outer landscapes has already begun.

Sinclair is amazed to find that, as a psychologist, Wilder Penrose is prescribing madness as a form of therapy at Eden-Olympia, which Wilder clarifies for him: “I mean a controlled and supervised madness. Psychopathy is its own most potent cure, and has been throughout history. At times it grips entire nations in a vast therapeutic spasm. No drug has ever been more potent.”

Even though to some extent Super-Cannes, like Cocaine Nights, uses the conventions of a detective novel it nonetheless contains few of the dead sentences a genre novel would have. There are no characters crossing the room to pour themselves a drink – instead they wonder “how the Reverend Dodgson’s Alice would have coped with Eden-Olympia. She would have grown up quickly and married an elderly German banker, then become a recluse in a mansion high above Super-Cannes, with a fading facelift and a phobia about reflective surfaces.” And yet there are passages that are almost parodic of Ballard’s “concrete and glass” period: “Her hip pressed against the BMW, and the curvature of its door deflected the lines of her thigh, as if the car was a huge orthopaedic device that expressed a voluptuous mix of geometry and desire.”

Ballard has said elsewhere that whereas the 20th century was mediated through the car, the 21st century will be mediated through the home, and as far as Super-Cannes goes home means work. “The dream of a leisure society was the great 20th century delusion,” says Wilder Penrose. “Work is the new leisure. Talented and ambitious people work harder than they have ever done, and for longer hours. They find their only fulfilment through work. The last thing they want is recreation.” There are references to the flats and houses of Eden-Olympia as service stations “where people sleep and ablute”. The real home is now the office.

It’s not quite correct to say, as some have, that Super-Cannes is a companion piece to Cocaine Nights though both take place within gated communities of one kind or another and both involve on a superficial level a naive narrator trying to solve a mystery. It’s more that some of the ideas in Super-Cannes are taken further than they are in Cocaine Nights. Ballard is unapologetic about this new employment of detective genre conventions saying that if it’s good enough for Dostoevsky in The Brothers Karamazov it’s good enough for him.

With his last two books one feels that he is reaching a new, younger audience – one perhaps attracted by the drug reference in the previous novel – and he obviously enjoys this as a professional writer, but as a knowing extract from The Kindness of Women shows, he has an instinctive feel for his core readership. This is Ballard describing the audience of an aversion therapy film at the Rio film festival: “…they gazed at the screen with the same steady eyes and unflinching expressions of the men in the Soho porn theatres, or the fans of certain kinds of apocalyptic science fiction.”

It seems that the “invisible literature” that he has written about, and which acts as compost for the mind, increasingly comes from the internet. Ballard doesn’t have a PC himself but his girlfriend, he says, supplies him with sites that might interest him: “She is a keen Net surfer, she’s constantly giving me fascinating stuff that she’s printed off. Extraordinary articles. Some really poetic, touching stuff. There’s one site that we first visited a year ago. It’s by these people at a bird sanctuary in Norfolk who have been tagging ospreys with radio transmitters [www.ospreys.org.uk]. They’ve been tracking their flights to and from their winter ground, an island off Ghana or somewhere, and they show maps of the routes taken by each bird flying across Europe and the Mediterranean, some of them detour for years before returning to this bird sanctuary. Watching all this is deeply moving. It lets another dimension into your life.”

|

|

Flight as a metaphor for transcendence occurs in Ballard’s work passim, and he has described in The Kindness Of Women how his own obsession with flying, which had started in Shanghai, had lead him to become an RAF trainee fighter pilot in Canada. “Flying is a very strange experience, it’s very close to dreaming,” he says. “The normal yardsticks, the parameters of our movements through space, are suspended. You’re travelling at 150mph, but if you\re 1,000ft up you’re not moving at all. Likewise, you can be travelling quite slowly coming in to land, yet you seem to be hurtling along like a Grand Prix car. The problem with light flying is that it’s very unstable and dangerous and also very noisy, there’s hardly any time to think.”

So, it’s a transcendental experience for him? “Yes, there’s no doubt about that. When I drive up to London, I go by London Airport and I always get a strange kick out of watching those big planes taking off and coming in to land. An empty runway moves me enormously, which obviously says something about my need to escape I guess.”

If Ballard’s interest in this bird sanctuary website seems apposite, then consider another of his favourites: “There’s this group that got into a disused American nuclear silo [www.xvt.com/users/kevink/silo/silo.html]. It’s wonderful! You’re taken on a tour and you can choose alternatives. ‘Would you like to look at the missile control room?’, ‘Would you like to see the sleeping quarters?’. It’s straight out of the stuff that I was writing about all that time ago.

“Sites such as these feed the poetic and imaginative strains in all of us who have been numbed by all the Bruce Willis films,” he says. “I’m waiting for the first new religion on the internet. One that is unique to the Net and to the modern age. It’ll come.”

Although he reads across the board of popular science, he says that he steers clear of cosmology books because “they are a happy hunting ground for, frankly, cranks. Multi-dimensional universes or strings and black holes – all this stuff is totally hypothetical.”

His friend Martin Bax wrote that Ballard has this amazing ability to know what’s going on in Cape Canaveral or anywhere without ever seeming to leave Shepperton, his home for the last 40 years. Sure enough, he’s got the goods on Channel 4’s Big Brother, although he claims not to have seen that much of it: “My girlfriend has been absolutely glued to it, she voted something like 30 times one evening! I think we can therefore discount the huge voting figures,” he says, with a warm, expansive laugh. “I’ve got a feeling people are just pressing the redial button.”

He doesn’t believe the official 7.5 million viewing figures (“that’s more than the number of votes that the Tory party got at the last election”) but he likens the interest in the programme to a Zen-like absorption: “If you focus on anything, however blank, in the right way then you become obsessed by it. It’s like those Andy Warhol films of eight hours of the Empire State Building or of somebody sleeping. Ordinary life viewed obsessively enough becomes interesting in its own right by some sort of neurological process that I don’t hope to understand.”

Is there not an echo of Big Brother in Super-Cannes when Paul Sinclair is at the Croisette in Cannes? “Without realising it, the crowds under the palm trees were extras recruited to play their traditional roles, when they stepped from their limos, like celebrity criminals ferried to a mass trial by jury at the Palais, a full-scale cultural Nuremberg furnished with film clips of the atrocities they had helped to commit.”

Ballard disliked the self-consciousness of Big Brother and would of liked to have seen more of a Truman Show element where the participants don’t know that they are being filmed. “It could be done. Candid Camera approached that slightly. You could just take people in a small holiday hotel on the Costa Brava and film it.” I suggest that this, as with certain psychology experiments proper, probably wouldn’t get past the relevant ethics boards. “Yes, that is the problem,” he says, as if it’s a minor but frustrating obstacle. “But then, afterwards you could say ‘yes, we did it without your permission but here’s a very large sum of money, sign this release form and you’re all going to be stars!’ ” In fact, the very next issue of New Scientist magazine that I picked up after speaking to Ballard had an article about a psychology professor at Stanford University who, frustrated at just those obstacles put in the way of research by ethics boards, is now running his own reality experiments in a TV series called Human Zoo.

“Most television is low-grade pap, it’s so homogenised it’s like mental toothpaste. But Big Brother as a slice of reality – or what passes for reality. It was like Tracey Emin’s Bed,” he says approvingly.

Ballard is worried that with all the interest in the internet we are forgetting what’s really around the corner: “The rapid development of the internet over recent years has rather shut out all discussion on the news about progress made on virtual reality. I assume that the world’s big electronic corporations are developing VR systems, which after all are going to take television and movies into completely new dimensions that I think potentially do represent a threat. When you enter into a simulated environment that is more convincing visually than the real world, the so-called real world, which of course is itself generated by the central nervous system,” he says, as if this is given a priori, “the temptation may be to stay there. It may lead to my phrase about playing with our own psychopathology as a game coming true with a bang. I see huge dangers there, but also huge possibilities. We might all learn how to play God! There might be a program along the lines of ‘Be a messiah. See what it’s like to be Jesus Christ or Buddha’!”

So God isn’t dead, he’s a latent component in a VR program? “Yes! Nietzsche was wrong!” he says triumphantly. “This might engender strong social changes, because most people have far more imagination than they realise, as their dreams make clear. Most people’s imaginations are damped down by the needs of getting on and making a living, generally coping with life and the imagination tends to be rather repressed in order to allow this flow.”

Surprisingly, for all his interest in film and an acknowledgement that it’s far more powerful than when it’s on TV, Ballard doesn’t go out to his local cineplex but watches rented movies at home. He gives a surprisingly prosaic reason for this: “There’s less rustling of chocolate papers.” Given that he’s a fan of David Cronenberg, and has generously praised his adaptation of Crash, it is also surprising that he hasn’t seen eXistenZ yet. “I hate all those VR pictures, especially the ones where people’s faces start to drip on to their chest and you realise,” he says with mock surprise, ” ‘My God, we’re in a dream sequence and the VR system has broken down!’ I hate that.”

For those of us desperate for more Ballard short stories, the news isn’t good: “I can’t see myself writing any for a while, partly because there’s nowhere to publish them. When I began writing short stories for sci-fi mags in the 1950s most of them were between 5,000 and 10,000 words. Now, magazines want 2,000 words or a 1,000 words – you can’t develop an idea. It’s not just a matter of knocking off a short story, it’s getting your mind into a writing phase where your imagination begins to think in terms of short stories rather than novels.”

For a writer who responds very much to social change, what does he feel will be the qualitative break between the 20th and 21st centuries? “If the 21st century represents a radical break with the 20th century then I don’t think that we’d be able to spot it. It might be something totally unexpected. It might be that our children and grandchildren vigorously reject the 20th century and everything it stood for. They may look back on it aghast and say ‘Who were these people? They spent all their time killing each other! Why?’. If consumer capitalism gets a little out of hand, and there are signs of resistance to the Americanisation of Europe, you might get absolute idealism in the young.

“The big change I assume is that there will be no more world wars, partly because no one will be able to borrow enough money from the World Bank to finance it. Now this changes the game enormously, it’s rather like playing chess and the rules being changed by the International Chess Federation ‘You don’t have to mate the king anymore’. ‘God, what do we do now!?’ I think the knock-on effect will be vast.” There is a certain glee with which Ballard accepts these changes, a state of grace that his protagonists strive towards.

“The decline of political ideology also changes things. There’s no real ideological clash between Dubyah and Gore for example. The decline of religion is also a factor. You do your triangulations and all we have left is consumerism, what I call the ‘suburbanisation of the soul’. That’s frightening. It may trigger all sorts of unconscious reactions. As someone in Super-Cannes says, in a totally sane society madness is the only freedom.”

This line has come up before in Running Wild for example? “Yes, I am tending to repeat myself in order to get the damn message home!” he says with slow emphasis before that gasping, generous laugh reverberates down the line.

Consider the word “triangulation” that Ballard uses. It’s a trope that almost uniquely marks out a Ballardian sentence with its three seemingly unrelated objects or events; as if he’s forcing the unconscious mind to construct a narrative to explain them. Take an example from Super-Cannes:

“Were assassins aware of the contingent world? I tried to imagine Lee Harvey Oswald on his way to the book depository in Dealey Plaza on the morning he shot Kennedy. Did he notice a line of overnight washing in his neighbour’s yard, a fresh dent in the nextdoor Buick, a newspaper boy with a bandaged knee? [my italics] The contingent world must have pressed against his temples, clamouring to be let in. But Oswald had kept the shutters bolted against the storm, opening them for a few seconds as the President’s Lincoln moved across the lens of the Zapruder camera and on into history.”

He says that he’s always been interested in content over style, even though he’s arguably our best stylist. “I don’t know if I am actually,” he says uncertainly, before warming to his theme. “I just want to push the message across. I don’t sloganise a political message but the sort of images that have appealed to me over the years – all the drained swimming pools, abandoned hotels, the strange business parks, gated communities and retirement complexes – these are what I want to convey, the peculiar latent psychology waiting to emerge into the daylight. That’s what I’m trying to do. Look at the world and see its latent content. I treat the external world as if it was a solidified dream.”

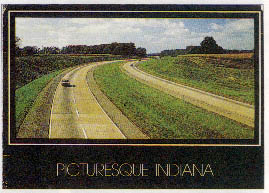

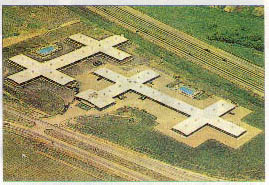

Boring Postcards USA

Ballard means this to apply to his life as well as his fiction: “With all the blandishments of advertisers and politicians, everyone is trying to sell you something. What are they really selling? What is the fashion industry really selling? Not just a new frock or a new pair of trainers, it’s selling something more than that.”

Super-Cannes involves a world where work is play and recreation doesn’t exist. Is writing, for Ballard, more work than play? “It’s part and parcel of the way I live. I mean, it’s not an extraneous activity. There’s no sort of office where, as it were, I say ‘right! I’ll have a cup of coffee and go through the day’s post’ It isn’t like that anymore.”

Ballard continues to be seen as a writer’s writer, his fiction a succès d’estime (Empire of the Sun notwithstanding), so it’s odd that at 70 Ballard still hasn’t had much of anything in the way of gongs. Germaine Greer has said that he is “a great writer who hasn’t written a great novel”. There might be something to this, that it’s his entire body of work that we should be assessing, not the individual novels. One can imagine that for Ballard it’s going to be like a great director or actor never receiving an Oscar for an individual film, but getting given one for lifetime achievement. How apposite that it seems we will be only retroactively able to acclaim his work in this way.

Of course, Ballard has always disdained or been uninterested in ingratiating himself with any kind of literary social scene. So maybe his lack of a public profile is partly a function of this. Plus the fact that he chooses to live in Shepperton (that locus of the twin Ballardian obsessions of flight and imagination, with its proximity to Heathrow and the film studios), out at the very edge of west London. He’s unlikely, for example, to be offered a South Bank Show after his comments last year about Melvyn Bragg’s dumbing down of the arts. And although he’s transcended the sci-fi genre in which he started (and transformed it) it’s hard to imagine him being particularly bothered about it. In this particular phase of Western literature, one of autobiography, perhaps a novelist of ideas, and rather outré ones at that, is simply unpalatable.

It’s often said that Empire of the Sun is his most nakedly autobiographical novel (along with its successor The Kindness of Women) and of course that’s true. But all of his fiction is no less autobiographical, even Crash, because of its exploration of inner space. One senses that he’s tired of this literalism, which has dogged him since he first started writing, and which reached its apotheosis with Crash. For example, a lot of people, he says, still think that he loves cars or that he’s a car buff (he drives a Ford Granada for God’s sake!) because of books such as Crash and Concrete Island, in his guise as poet of the motorways. “I’m not interested in cars at all. But I am interested in the psychology of the car user, the car as a facilitator of latent psychopathy or of the latent imagination for good. I think that a lot of people do express their imaginations through the cars they own. Imaginations they wouldn’t be able to express in other ways. Cars are a hugely liberating force in all kinds of ways.”

Boring Postcards USA

So he doesn’t agree with groups such as Reclaim the Streets or the wider eco movement? “I don’t agree with the Reclaim the Streets people at all. I think that the recent petrol tanker blockades across the country illustrates how silly it is to talk about the end of the car age. It hasn’t ended: more of us have cars and drive further in them than ever before.” Or as Paul Sinclair puts it in Super-Cannes: “Fanatical Greens always veer off course, and end up trying to save the smallpox virus.”

When the fuel crisis was at its worst there was the very real possibility that there would be thousands and thousands of abandoned cars on motorway flyovers and cloverleaf intersections. And this recent prediction that a giant tsunami is going to swallow the east coast of America. All very Ballardian. “I know; I feel I’ve been here before,” he says, as if his fiction was a parent and reality was a child lagging behind. As usual he’s done his triangulations.

Angela Carter once said that there is an element of Glen Baxter’s humour about Ballard’s fiction, and in a way that’s right, there is this possibility that it might descend into the ludicrous at any moment. But the point, surely, is that it never does. What humour there is is really so black that it could never escape the event horizon of laughter. No, a much better analogue is to be found with Martin Parr’s collections of Boring Postcards, especially his latest, Boring Postcards USA. Here we find interchange complexes, vast turnpike systems, interstates, thruways, empty hotel lobbies, freeways, bus depots, office buildings, shopping malls, trailer villages, in short all those images of our waking, solidified dreams that most of us look at and find ugly or brutal but which when viewed through Ballard’s visionary protagonists in their dry, affectless realms, are transformed into something meaningful and life affirming.