Chris Hall has a lively conversation with Will Self

Although, at 39, Will Self is approaching mid-life and he can see the “lowering storm of age and extinction” ahead of him, there is still certainly nothing in his prose or his physiognomy to suggest that he will become flabby or paunchy. Indeed, even though his new novel How The Dead Live is divided up into sections of “Dying”, “Dead” and “Deader”, Self has if anything attacked the page with even more vigour and purpose than before.

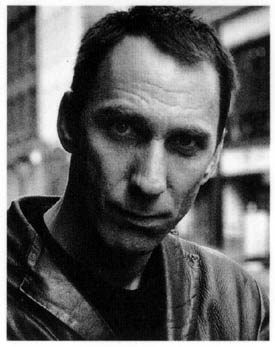

So it’s rather reassuring to see Self looking very healthy, tanned as he is from a holiday in the Canaries, reassuring also that the Coke he orders comes in a glass with ice. We meet at the Groucho Club in Soho, London, one of Self’s former haunts but which he says he hardly ever visits anymore. Outside he crouches down to chain his 22cc Go-Ped Bigfoot – a small motorised scooter – and strides into the bar wearing a black leather jacket, crisp white shirt and a pair of well-worn brown Chelsea boots to go with his new cropped haircut.

How The Dead Live is a mordant and disturbing allegory of life after death and death in life, which derives some of its structure from The Tibetan Book Of The Dead. Of course, Self has used that particular book in his fiction before: “The North London Book Of The Dead” from The Quantity Theory Of Insanity and a chapter in My Idea Of Fun. But whereas “The North London Book Of The Dead” was about the failure of a young man to come to terms with the death of his mother, How The Dead Live is very much an objective description of what happens to someone in the after-death plane. That someone is Lily Bloom (an evocative name, encoding notions of life and death), a 65-year-old American anti-semitic Jewish wiseacre who at the beginning of the novel lies dying of cancer in the Royal Ear Hospital in London. It is a Self-like irony that it’s a stiff who provides him with one of his most fully realised characters, especially given that he has been dismissive of the very notion of character in the past.

Self wanted to call the book Deader, but his French translator persuaded him not to, and instead suggested the eventual title, which is also the title of a French film from 1999. When Self was sitting in his study one afternoon mulling this all over, the title of a Derek Raymond book (aka thriller writer Robin Cook) swam out at him, and then, he says, he really did have some agonising over it. “How The Dead Live isn’t perfect for the book,” he admits, and says that initially he wrote an exculpatory forward explaining why he’d chosen the title. “But then, I very much wanted to take my voice out of this book. I wanted How The Dead Live to just happen in the reader’s mind, decoupled from any presuppositions about any framing of the text in that way.” Once again, it’s a novel where the moral fulcrum is someway off the page.

Although Martin Rowson’s endpaper maps attempt to locate the fictional topography of How The Dead Live the world it describes is very much filtered through Lily. In other words, as the preface from The Tibetan Book Of The Dead says, it takes place on Lily’s “mind stage”. Lily’s venom and disgust, her vitriolic wit and bile is well sustained over the 400 pages,.but the ultimate effect is one of poignancy, of playing to the empty gallery as she clings to her personality. With his latest novel, Self has gone to the core of the belief that the essence of the self is the personality.

So does he have semi-mystical beliefs about death himself? “I have completely mystical beliefs in that area. I’m off with the fucking fairies,” he says, laughing. “I always have been. I’ve never been a materialist particularly, I’ve always been a transcendental idealist.” So why the obsession with The Tibetan Book Of The Dead? “I’ve had this preoccupation with it from when we were sitting around rolling joints on it in the late 70s, and it’s perrenial in my work. The point is that when you push materialism as far as it can go then it really shows itself up. People who say they are materialists, they’re hoisted by their own petard. I don’t want to sound like a character in “Ab Fab” who wants to give it all up and bang tambourines with a bandeau, but that’s pretty much how I feel at the moment. People aren’t really materialists, they don’t really want the car, the house, the Phillipe Starck juicer, they actually want the cachet, the status and the culture that go with those things.”

Self is keen to stress that the novel is what it appears to be: “It really is a book about death. It’s a Buddhist allegory,” he says, allowing that of course there are satirical elements. When Lily Bloom, newly dead, is taken away in a mini cab to a suburb of London called Dulston – really a disintegrating part of Lily Bloom’s own psyche of course- she goes to a meeting of the Personally Dead, where they have a 12-step programme for those who can’t or won’t come to terms with being dead.”Why didn’t it even occur to me that there was only one person who could’ve arranged these particular elements of my own experience, and cobbled them together into this dreary scene?” At one of the meetings someone speaks on the topic of “Why Are We Dead?”, about “how disturbing it was to realise that style was personalty, and that our sense of self was nothing but mannerisms and negative emotions.”

Lily gets a job at Baskin’s Public Relations when she is dead, “typing up still more releases on fresh kitchenware, country club launches, innovatory thermal socks – whatever new effluvia were next to join the ever widening torrent of increasingly trivial innovation.” (There is a great AJ Ayer joke, in that “death hadn’t thawed his notoriously glacial logic”, and “only such a relentless rationalist could gain any succour from these, the nervous tics of the afterlife.”)

One of the first things that happens to Lily is that she squints down “and there, pirouetting between my knees, is a tiny grey manikin. It’s no more than a couple of inches high and has the aspect of a foetus, but a foetus of around 20 years of age.” Lily’s spirit guide, Phar Lap Dixon -a terse and gnomic aboriginal man – explains that it is a lithopedion, a “little dead fossil baby of yours, yeh-hey!?” The idea for the lithopedion, explains Self, comes from “a bizarre transmogrification of a story called ‘Caring, Sharing’ where people have these giant, half-children called emotos who look after them and carry them around. Just as much as you internalise the parent, so you externalise the child.”

I ask him about the novel’s fantastically bleak ending, where Lily is reincarnated as her junky daughter’s junky daughter. “Yes, it’s certainly not up and light is it?” he says mockingly, drawing hard on a white filtered cigarette. “The end acquires this ineluctable and dangerous feeling logic that did surprise me. I hope people will feel that the back end of the novel is like a whirlpool, like some Edgar Alan Poe story dragging you in.

“There was this case, a tragic, tragic case, of this toddler who was discovered to have starved to death because her parents had taken heroin overdoses, and I was really shocked by this case. But I have to say that the student and practitioner of Grand Guignol that I am of course filed it away for a future story.” Do you mean consciously? “Yes. I was talking to Martin Amis about this case, and I said it would be interesting to write about it from the child’s point of view, and Martin said ‘Ah, yes’ with a gleam in his eyes – because he’s a great one for thieving ideas himself – and he said ‘But how would you do it?’ and I hadn’t thought of that particular form of ending until I was two-thirds of the way through. That’s the great thing about being a writer, you file these things away and there’s this amazing moment when you realise why you filed it away. It seems like serendipity, but in fact it gives a purposiveness and a plotiness to your own work.”

In one of the more bizarre reviews of How The Dead Live, Self has been criticised – among all the usual gubbins about being “negative” and obtuse – for not being lyrical. Would he agree? “I think I often see it as being intolerably precious, actually. There’s a whole swathe of” – and he pronounces the next two words as if they were something unpleasant leaving his mouth – “English literature that is shite, precisely because of that. It’s overly precious, and it tries to talk about contemporary life using models of the sentence, the paragraph, the chapter, at all levels of the text, that are derived form archaic forms rather than being absolutely present and imminent in the way that we perceive the world now.”

Self has also just finished a three-year stint writing a column for the weekly architectural journal Building Design, in which he has addressed, among other things, how we perceive the built environment today. Ellipsis has just published more than 60 of those columns in Sore Sites. Why did a high-profile novelist write for a relatively obscure trade journal in the first place? “Well, I was asked by the incoming editor of Building Design who had a brief to bring in someone to reflect back to the architectural profession on how lay people view them and their work, and that just seemed like a really interesting idea to me,” before self-depracatingly adding: “It was also an opportunity to once again get the old rotrings out and do my egregiously bad and amateurish cartoons.”

In fact, as a look through a collection of his cartoons in 1985 for the New Statesman called Slump will reveal, while he is no Ralph Steadman or Gary Larson, he is being unduly modest about his self-taught cartooning skills. Slump is a witty, charming and caustic look at life through the lens of a man who decides never to leave his bed.

One of the pieces that Self wrote for Building Design, and which is not collected in Sore Sites, was an obituary of his father Professor Peter Self, one of the founding members of the Town & Planning Association, written just hours after his death in Canberra, Australia. “Some readers may feel that it’s either macabre or insensitive for me to be writing this within two hours of his death, but believe me,” wrote Self revealingly, “it’s what he would have wanted. Wanted because he raised me first and foremost to be a thinker, then secondly a pedagogue, and lastly a writer.” Self omitted the piece partly because he’s had some problems with memorialising people before. “It’s a funny business, you’re not quite sure how to do it, and in what context it’s appropriate.”

He says that there is some bad blood between him and his American publisher, The Grove Press, over having his introduction to “The Book Of Revelation” dropped because it wanted another writer. (It was originally published in Britain by Canongate.) Self’s intro was a memorial to his friend Ben Trainin who died aged just 28 in 1985. He hesitates, before going on to say: “To be honest, Ben’s oldest sister wasn’t happy with it, and maybe I should have been more sensitive to her feelings about it. On the other hand, I don’t feel it was in any way a traduction or a cheapening of his memory at all. On the contrary, I thought it was a felt and important memorial to a really quite remarkable man.”

Apropos the new novel, can we see a foreshadowing of things in the following passage from the introduction to Revelation? “Funny how the dead get deader. Ben was dead from the moment he died, but five years after his death he was deader, and now he’s deader still. I know this because of the anachronistic quality of my vision of him.”

Self was due to meet William Burroughs, just months before he died in 1997. Is he upset that he never met one of his favourite authors? “There was a plan to meet with Burroughs, but I’m not too bothered about it though. I mean, the poor guy was turned into a bit of a Salvador Dali figure in the last years of his life,” he says sadly. “But of course the great thing about literature is that quite a personal psychic communion exists between the text and the reader. You just don’t have to meet the author.” (Though try telling that to Martin Amis who once fled for his life after a callow fan by the name of, ahem, Will Self chased him down the street!)

Does he read any “invisible literature” in JG Ballard’s phrase? “Oh, what Black Box Flight Recordings? I don’t want to read that. I’m terrified of flying at the moment,” he says anxiously. “But, no, I don’t find the poetic at quite that level. I love reading books about a fact, whatever that fact may be.

“I get to read a lot of non-fiction for reviewing, and I enjoy it. I don’t feel unsustained,” he says, marvelling at how his contemporaries say that they read so much new fiction, which he has little interest in. “Of course, like all of us, I feel that I should be re-reading Proust,” he admits. “I considered doing this project that the telly people have been on at me to do – a history of the 20th century novel [one that Amis turned down, incidentally]. The idea that appeals is the excuse to re-read, or read for the first time, an immense number of 20th century novels.”

In David Lodge’s Small World a writer discovers through a computer program that the most common “lexical” word in his oeuvre is “greasy”. What does Self think an analysis of his new novel would come up with? “Well, in The Quantity Theory Of Insanity one critic said that ‘subcutaneous’ came up a lot,” he answers, before deciding what it would be. “In How The Dead Live the characters are always warbling, as if there’s some sort of infernal chorus of grey doves.”

Ah yes, grey… It turns out that Self is colour blind to an extent. “I see colours at a much reduced level of discrimination, and then I can’t identify them solus either. It’s pretty awful. I found out at school, but I didn’t realise how radical it was until recently when my wife, who has such a fine eye for colour, spotted just how bad it is. It’s just not a very salient thing for me,” he admits. “If you noticed in my books there aren’t really any colours in them.”

Of course, the title of one of his collections of short stories, Grey Area, obviously leaps to mind here, and also his interest in structure and form as opposed to surface detail. Also, at the end of How The Dead Live, Lily gives a long series of synonyms for grey: “If I’d had the opportunity I never would’ve called anything ‘grey’ again on this go-round. Oh no, it would’ve been canescent, griseous, dove-grey, pearl-grey, cinereous, fuliginous, or écru”. Could it be, perhaps, that this very lack of colour discrimination has meant that Self’s eye has, far more than most writers, adapted to the dark lens of London’s drab facade, its inhabitants as well as its built environment. As Lily says: “London, where people are still so fucking reserved, so polite, so hidden behind gauzy indifference. Their politeness is killing me.”

Earlier in the summer this year, Self agreed to become an “art exhibit” at the Fig 1 gallery in central London. He was sat at an architect’s desk with a laptop, wearing wraparound shades, and having his words projected on to a plasma screen behind him while a small audience watched. “If anyone’s got a problem with writer’s block that’s the way to cure it,” he says with total confidence. “You’re sitting there with 30 to 40 people with nothing to do but write, and a necessity to entertain them. The word rate goes up from 300-500 words an hour to about 1,000 words an hour – a colossal production.”

So was he happy with the end result? “It has a certain charm, but I’m not sure I’d like it classed with my works that are constructed, as it were, in tranquillity. My publishers are farting around at the moment but they will bring it out in a kind of lavishly tooled arty farty volume.”

There are plans to repeat the exercise with some modifications in America next year. The main problem it seemed was that people treated it a little too reverently, and so two-way mirrors are being considered, as well as directional mikes. “I had hoped people would come in and talk among themselves, and that I could lig their dialogue and build things up a bit, but the gallery atmosphere intimidated them a bit. But the main aim, which was to yank the writer back into the situation of being a storyteller in the immediate present, sort of worked.”

Although Self says that it was an interesting exercise, there was a particularly unsettling moment during the five days that he was there. “One evening I’d written at great length about this Chinese girl who was there, and of course she disappeared; but by then she’d become quite a major character who then reappeared again towards the end of the day. When I was leaving she button-holed me outside the gallery along with a posse of other people, all of whom I recognised as being characters in my story, and said ‘Come for a drink with me’ – I reared back and she said ‘Oh, I suppose you find it really disturbing to have to come and have a drink with one of your characters?’ And it certainly was. And I didn’t do it!”

Of the Internet as anything other than a high-speed research tool and messaging system, Self says that he is uninterested. “McLuhan was wrong, the medium isn’t the message. It’s another device that allows one to suspend one’s disbelief.” Another fact that could almost be a conceit in his own fiction is that Self’s name is “semantically camouflaged” as far as the internet is concerned. Indeed, most search engines will discard the “Will” leaving you with a list of self-help books, etc. On the subject of his name, which a lot of people still seem to think is a nom de plume, Self tells me that if you look at the credits of old “Batman” episodes you’ll see that the producer was none other than William Self.

Indeed, Self continues to crop up in similarly obscure areas of TV: “I’ve been in the credits of ‘Brass Eye’, ‘The Day Today’ – ‘horse ripping by Will Self’,” he says proudly, being a big fan of Chris Morris. Is that horse in the sense I think it is (heroin)? “It could be, knowing Chris. I hadn’t thought of that actually.” He even gets a mention in “Father Ted” as someone who reads Brick magazine.

For anyone who saw the Channel 4 discussion programme “Something of the Night” (re Ann Widdecombe’s comment about ex-home secretary Michael Howard) with Self presenting, he says that it’ll be the last time he does anything like it again: “It was ill-advised. The anchor role really vitiates against being radical or presenting an alternative voice.” Which is a shame in a way because, for all Self’s obvious discomfort, it was very entertaining to have him try and steer a path between voices as diverse as Martin Amis, Paul Johnson and Tracey Emin (who was embarrassingly drunk for the second time in as many weeks on a TV programme).

As anyone who saw “Room 101” on BBC2 recently, in which celebrities get to nominate their pet hates for eternal banishment, it will come as little surprise to learn that Self’s hatred of logos and branding has extended even to his own car, a Volvo 360 turbo, from which he removed all of the Volvo insignia in an attempt as it were to be left with the Platonic ideal of a car. “Perhaps I’m becoming insidiously less radical but I’ve failed to take any of the identification tags off the new one,” he says, slightly annoyed with himself. “It really looks like a Volvo. I must get that done, actually.”

As for the future (apart from taking a screwdriver to his latest family vehicle that is), Self says “there are long lain plans to turn ‘The Rock of Crack As Big As The Ritz’ [a short story from Tough Tough Toys For Tough Tough Boys] into a kind of… reggae opera. Not staged,” he hurriedly explains as he sees my bemusement, “but as an album! I’ve got two friends who are excellent reggae musicians and producers who’ve worked on a five minute section of the text and have done great work with it.” If the result is anything as good as the track “5ml barrel”, his collaboration with Bomb The Bass, outtakes from the short story “Scale” from Grey Area, then it should be worth the wait. And if all that sounds unlikely, his next book, he says with a straight face, will cover postwar farming history: “A classical novel about land use.”

© Chris Hall 2000