Elizabeth McCullough digests two takes on eating disorders in Marya Hornbacher’s Wasted and Marianne Apostolides’ Inner Hunger

Joining an abundance of self-help and resource manuals on the topic of anorexia and bulimia are two recent first-person accounts from sufferers of these disorders. Though speaking with very different voices, the authors of Inner Hunger and Wasted have the same story to tell – a story of cultural pressure and family dysfunction, merciless self-discipline, and, in the end, a strangely mundane redemption from a self-imposed hell, a story that’s familiar to us from the days of Steven Levenkron’s The Best Little Girl in the World . The influences on the development of eating disorders and the devastation wrought by them should by this time be well-known. As new contributions to this genre appear, the question becomes, What purpose do these memoirs continue to serve? What do they tell us, not just about girls with eating disorders, but about ourselves?

Marianne Apostolides’ Inner Hunger is the most conventional of the two accounts. Both personal and informative, Inner Hunger begins with a balanced treatment of the usual suspects in the development of eating disorders, namely, family, biology, and culture. Apostolides attributes her own eating disorders (both bulimia and anorexia) to her inability to develop a strong sense of self to tide her over the inevitable disappointments of adolescence. Apostolides sees the course of her disease as a series of attempts to create an acceptable identity for herself. Because she can’t be dainty, smooth, and popular, she takes on the identity of anorexic as a way of coping. Having an eating disorder solves a lot of problems; as Apostolides explains, reducing your world to a count of calories in and calories out makes a big, uncomfortable, awkward world small enough to handle.

She begins noticing, however, that there are people in the world who don’t buy into the cultural norm that thinness equals success, who don’t seem to care so very much what other people think about them, and who aren’t spending their lives torturing themselves with food. Apostolides reasons, if I could just be more like those carefree spirits, if I dress differently, think differently, act differently, just like they do, then I won’t be the culturally sanctioned kind of normal — but at least I’ll be normal. What saves Apostolides is not getting in touch with her “true” identity or building a strong sense of self, however; she is not any more successful than the rest of us in forging an impenetrable armor of selfhood that will protect her from the slings and arrows of life. What saves her is her gradual acceptance of her own flawed humanity, and her relinquishment of the need to be anything in particular.

Apostolides ends her book with advice for communities, institutions, parents, mentors, as well as women with eating disorders. She advocates a change in the messages that our culture sends young women about body type, beauty, and success. She counsels parents to reach out to their troubled daughters with empathy and compassion. Putting a positive spin on a dreadful disease (“we are strong to have found a way to survive when we weren’t offered the support we needed”), she urges young women who recognize themselves in her story to seek help. All this is very inspiring, but there is nothing new here, nothing that deviates from the well-worn story of cultural pressure, dysfunctional parenting, and secret obsession. Apostolides does not ask herself and her readers why, in 30 years of scholarly and popular consideration of eating disorders, we have not found a way to stop girls from starving themselves to death. Is it possible that the answer is not that we don’t know how, but that we don’t want to?

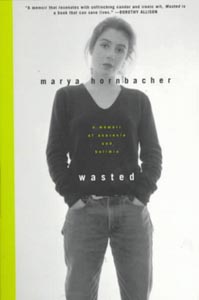

Wasted, by Marya Hornbacher, is a strong contrast to the more gentle Inner Hunger in its unsparing, in-your-face approach to the eating disorder story. Playing on all the meanings of the word, Wasted is an account of the author’s lost youth, misspent in intoxication with starvation. Turning The Best Little Girl in the World iconography on its head, Hornbacher becomes instead the Worst Little Girl in the World, shooting up, sleeping around, and swearing like a sailor by the age of 16. Hornbacher attempts to deflect the blame from her narcissistic, oblivious parents, and onto a culture that lures women with promises of happiness while robbing them of their power, pressuring them to take up less and less space until they finally disappear. But like Apostolides, she’s reluctant to give up the romantic idea that her eating disorder is really, at its heart, a reflection of her own special status as someone who can’t and won’t fit in.

Unlike Apostolides, whose holistic philosophy (nurture your mind/body/spirit; get in touch with your True Self) is comfortable and non-threatening, Hornbacher is hard to cozy up to. She holds us at arm’s length with her intelligence and her suffering. Medical professionals and psychologists are dismissed as inept “shrinks” who can’t possibly know what it’s like to have an eating disorder, how special it is, how unlike other, more treatable, less complex conditions. Fellow sufferers are likewise shoved aside as part of the homogeneous mass of good little girls striving to live up to other’s expectations. And the rest of us, those of us who can’t possibly know what it’s like because we haven’t been there, are “people,” as in “People take the feeling of full for granted,” and “People have this idea that eating-disordered people just don’t eat.” There’s people, and then there’s Hornbacher, a genuinely talented and gifted person, who believes her main problem is that she will never to live up to her own expectations to achieve something grand in this life.

Hornbacher refuses to give us the neat story we’re expecting. About two-thirds of the way into her account of her youthful flirtation with death, she experiences an epiphany. Committed to a mental institution, she is forced by the staff there to do what she has thus far been supremely successful in avoiding: experience her emotions, rather than intellectualize them. Instead of getting better and better after this breakthrough, triumphing over death and disease and finding happiness in Recovery, she begins another agonizing slide, getting really serious about starving this time, punctuating extreme self-deprivation with occasional frenzies of gut-wrenching bingeing and puking. Suddenly, the end arrives, and it is unexpected and disarmingly simple: while pouring a can of juice down the drain in the emergency room, she has the thought: “What does this prove?”

The aftermath, as the title portends, is not all happily ever after. Hornbacher remains haunted by the specter of a wasted youth and a foreshortened future. Health is an unattainable ideal; her body and her mind will never recover fully from the ravages of her eating disorder. There’s bitterness in Hornbacher’s epilogue, but that’s understandable when one remembers that she was still in her early 20s when the book was written, too young to understand that everyone’s life is shaded by regrets and by dreams that won’t come true, and that while her regrets and disappointments are different from most in kind and degree, she’s really only struggling with the same problem we all have: the problem of being human. Not special, not charmed, not blighted, just human.

At the end of their stories, neither Hornbacher nor Apostolides is able to step back far enough from their eating disorders to really tackle what comes next. Their memoirs are to some extent a reflection of the same issues that underlie their disorder: an obsession with “specialness.” The specialness is no longer about being the thinnest, of course; now it’s about having a unique redemptive story to tell. But if redemption is to come from the testimony of the victims, why are we still waiting? Eating disorders are reported to be rampant among adolescent girls and young women. If these books contain the answers, why hasn’t the problem been solved already?

The authors are right to indict a narcissistic culture as a contributor to their disease. To the extent that cultural pressure is responsible, we’re all responsible, and we all should heed what these women have to say. We’re reading the books, but are we saving any lives? Though they are marketed as cautionary tales, the accounts themselves offer abundant evidence that they will be ignored. Though each of the authors was told repeatedly during the course of her illness that she needed to change her behavior, each of them resolutely minimized the severity of her disorder, hid her symptoms, rationalized her behavior, and took pride in her success in doing so. What makes the authors think that other, similarly deluded women in the grip of an eating disorder will listen to them? If anecdotal accounts are to be credited, books like these, far from being helpful, actually contribute to eating-disordered behavior by serving as “how-to” manuals. Likewise, the authors want to reach out to the friends and family of eating disordered girls. Again their stories belie them, as they describe how time and again their own family and friends made them crazy, let them down, ignored their symptoms, or, as Apostolides patronizingly explains, needed “time to learn how to give support.”

Who wants a cure, anyway? According to Hornbacher, not the experts – they’re too wrapped up in their smug theories, their own pet stories about eating disorders. Parents would like a cure for their daughters, of course, but Apostolides cautions that it probably won’t be at the expense of changing themselves. And society, which is you and me, certainly doesn’t want anything to change. If we did, we’d have to do a couple of things. We’d have to stop telling each other that Culture is something that is out there doing things to women, as though we were not personally involved in the process. We’d have to stop hysterically insisting that eating disorders are everywhere, while simultaneously turning a blind eye to the sufferers in our midst. These are the tactics that we use to deceive ourselves that we’re doing something about the problem when we’re really just making a lot of noise and enjoying the show.

There are alternatives. We can stop taking ourselves so seriously and have a good laugh at the ludicrous notion that being thinner, or being anything, will make you more successful, interesting, and loveable. Righteous indignation isn’t working, and a good laugh can’t do any harm. We could even take a five-minute break from obsessing over ourselves and blaming culture and parents and biology for our problems and think about someone else for a change. What this comes down to, is that we would have to stop pointing the finger at girls with eating disorders and start looking at our own destructive obsessions. Just because we don’t all starve ourselves doesn’t mean we aren’t engaged in the same futile war with our own basic humanity. Wouldn’t it feel good to just give up the struggle to be perfect, successful, rich, thin, happy? Maybe you don’t tell yourself, if only I were thinner, I’d be happier, but I bet you do tell yourself, if I were only more something or less something else, I’d be happier. Take a break from the struggle and ask yourself, along with Hornbacher, What does this prove? Stop trying to be happier. Stop trying to be. Stop trying to. Stop trying. Stop. There, doesn’t that feel better?