Gary Marshall

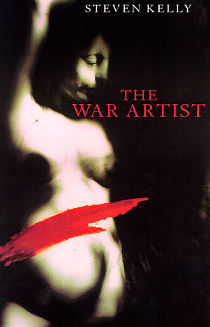

Steven Kelly is the editor of online UK literary magazine The Richmond Review and, being mature professionals, we were looking forward to sticking the knife into this, his fourth novel. All in the name of highbrow literary criticism, of course. Unfortunately for us, The War Artist is great.

Although the plot initially seems simple, The War Artist is a strange and complex novel. The book tells the story of Charles Monk, a uniquely talented artist whose paintings are uncannily lifelike. Equally fascinated and appalled by war zones he paints the suffering and shock of soldiers and civilians alike, but the actual machinery of war is conspicuous by its absence. Rather than describe the war zones in straight reportage, the horrors are conveyed instead by gallery descriptions of Monk’s work. The effect is chilling, pictures of shattered skulls or screaming women described in cold, unemotional text: “Goatfuck. 1991. Oil on canvas, 46.6 x 34cm. Portrait of dead Iraqi conscript with half of head missing. Private collection”.

True to his name, Monk is a solitary and insular character, “a war junkie… transfixed and blinded, rabbit-like, by the cold inferno of suffering around him”. At first his coldness and insularity seem the obvious consequence of his vocation, the emotional protection of the professional voyeur who has “seen too much”. We first meet him in a dilapidated Gentleman’s club, eating and drinking to excess whilst annoying the resident poet. Over the course of the novel we learn of his days aboard smuggling ships, his involvement in a shipping magnate’s empire and his painting of Miriam Janssen, his best friend’s wife, which is so lifelike that nobody is allowed to see it. One character has his eyes put out for gazing upon the painting, one of many mythical echoes which reverberate throughout the novel.

As The War Artist develops we are introduced to Claude Tartaro, a fan of Monk’s work whose attempts to understand the artist lead him to uncover a much darker side to Monk than he anticipated. As his investigations continue we discover that Monk is is no whiter-than-white hero who dispassionately observes and depicts the atrocities around him.

Feeling that Tartaro is too diligent in investigating a long-forgotten murder in which he is implicated, Monk creates a unique work of art for him: “Hunger as a motivating factor in the issue of war, Part II – 1989. Flesh and blood on cotton. 150 x 210cm. Dead dog spreadeagled on cotton bedspread with stomach slashed open. Private collection of M. Claude Tartaro: gift of the artist… the work serves as an invitation to the critic to consider his own mortality in the context of his current investigations”. As the paths of Monk and Tartaro collide the novel builds towards a violent climax which resurrects the mythical themes first raised in the novel’s early chapters.

Ranging from the Sorbonne to Khe Sanh and modern-day London, The War Artist is written in a sparse, economical style which deftly sidesteps the danger of pretension whilst encompassing classical mythology, obsessive love, the relationship between art and life, underage sex and spaghetti westerns. And you can’t say that about very many novels.