Gary Marshall

As far as John Diamond was concerned, cancer happens to other people. A columnist who is paid handsomely for spouting off each week about whatever is on his mind, he undergoes tests for the lump in his neck and, rather than panicking, sees it as a potentially interesting anecdote. “I imagined myself in a week or two’s time not as someone who had been diagnosed as having cancer but as someone who had had a close brush with cancer – who’d been through all the tests and then at the very last minute been given the all clear. If anything it sounded even more heroic than the real thing“. By this point Diamond had had cancer for more than a year.

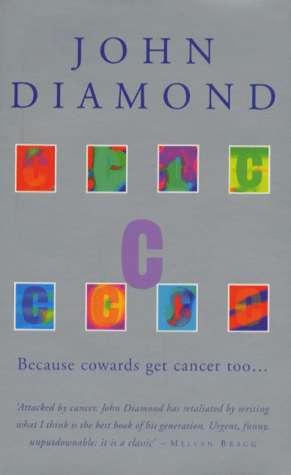

“C” is, of course, about cancer – what it is, what it feels like to receive the diagnosis one evening as you’re watching Eastenders, how it feels to lose four stone and most of your tongue. Subtitled “because cowards get cancer too”, the book makes no attempt to portray Diamond as some brave, heroic figure and describes his twisted pleasure as he uses his illness as a weapon at dinner parties, his frequent outbursts of impotent rage and the often appalling way he treats his wife during his convalescence.

This is no self-pitying, “poor me” tale. Diamond describes how cancer works, clear-up rates, the different sorts of treatment and their chances of success. A savagely perceptive writer, he pours vitriol on new-agers and pro-smoking campaigners in equal measure. “By all means campaign for some phantom ‘right’ to smoke, but don’t believe that right derives from corrupting the statistics about what smoking does to you. Understand it for what it is: the right to play Russian roulette, as I did, with the immune system“. Diamond’s descriptions of his predicament are frequently hilarious – his inventory of his well-stocked medicine cabinet reads like PJ O’Rourke, albeit PJ writing about morphine instead of cocaine.

Diamond reserves his most vicious criticism for those who believe surviving cancer is a matter of the correct mental attitude, as if those who die simply didn’t try hard enough. As he recounts his treatment through his weekly newspaper column he receives regular missives from the terminally stupid, “the ones who told me that as a journalist with a public platform it was my bounden duty to stop operating as a propagandising dupe for the evil medical establishment, to tell doctors that I wasn’t fooled by their fake radiotherapy statistics when everyone knows that radiation kills, and to put my faith in the Bessarabian radish, the desiccated root of which has been used for centuries by Tartar nomads to cure athlete’s foot, tennis elbow and cancer, as detailed in their book Why Your Doctor Hates You And Wants You To Die, review copy enclosed“.

Currently cancer-free, Diamond would shy away from any suggestion that his illness has been in any way a positive experience. There is, however, a positive message to his story which is best illustrated by one of the book’s most poignant and telling scenes: Diamond is in his car, not long after the treatments that removed most of his tongue and destroyed his taste buds. Listening to a familiar show he hears a voice he can’t place, then realises that he’s listening to his own voice on a programme recorded a year previously. Diamond is struck by the difference between the man he is now and the man whose voice is broadcasting through the ether: “he was the one who didn’t realize what a boon an unimpaired voice was, who ate his food without stopping to think about its remarkable flavour, who was criminally profligate with words, who took his wife and children and friends for granted – in short who didn’t know he was living“.

Rather than denying mortality, “C” suggests that it’s only when you understand the fragility of life that you can fully appreciate just how magical and wonderful day-to-day existence can be.

Coda:

John Diamond died on 2nd March 2001. The Guardian obituary has the full details of his remarkable life.