Gary Marshall

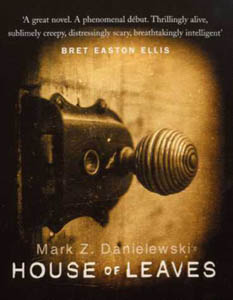

House Of Leaves is one of the strangest books we’ve seen for some time. With multiple narrators, a mass of footnotes and direct transcripts of video tapes, the novel has been described as a "literary Blair Witch Project’ – a description we’d wholeheartedly agree with.

The novel is narrated by Johnny Truant, a bar-hopping low-life who is losing his grip on reality. When an old man – Zampano – dies, Truant grabs a manuscript from his apartment and takes it home to read it. This manuscript is an analysis of The Navidson Record, a collection of videotapes that record some spooky goings on in a suburban house. As Truant reads the manuscript, he reproduces it in full, sharing his observations with us and describing his own increasingly fragile mental state.

There are three main stories in House Of Leaves: Truant’s reactions to the manuscript, Zampano’s analysis of The Navidson Record, and the contents of the videotapes themselves. As the novel continues, each story overlaps. Zampano adds extensive footnotes to his work and attempts to contact the famous people (Stanley Kubrick, Steven Spielberg, Camille Paglia) mentioned in the tapes; Truant attempts to explain the more tortuous footnotes, adding explanations and analysis of his own, and unnamed "editors" in turn comment on both Zampano’s and Truant’s comments. The Navidson Record would have made an excellent spine-chiller in its own right, but the analysis and footnotes rack the creepiness up by a notch. In the early stages of the transcripts, we know that something scary’s going to happen: the footnotes tell us so.

As if the layers of comment weren’t complicated enough, after a few dozen pages things go completely mental. The word house is printed throughout in blue, without explanation; footnotes become longer than the sections they’re commenting on, print is ![]() or

or ![]() ,

, entire sections are crossed out; some pages contain a single word or letter, while others are filled with lists of buildings or household amenities. All of these things are reproduced faithfully, resulting in pages where the only text is "XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX", other pages with letters and words missing due to "fire damage" (the gaps are replaced by spaces and square brackets), still others with text at crazy angles or tiny font sizes. If you attempt to read this book in the bath, you’ll probably drown.

The book’s ambition is also its downfall. The crazy typography and constant interjections from Truant (and others) make it difficult to follow parts of the story and, in the early sections especially, you’ll be sorely tempted to throw the book out of the window. Many of the tangents – psychological theories, local history, analysis of photographs, lists of camera equipment – overstay their welcome, and the ending is curiously flat, as if the writer suddenly ran out of ideas. Some scenes jar with the rest of the book; in particular, Truant’s description of his trip to a bar, where he talks to a band and discovers they’ve read the book he’s still writing. This is either an unintentional error or – even worse – a ham-fisted "it was all a dream" scenario lifted straight from an episode of Dallas.

House Of Leaves is a brave attempt to do something different, updating Burroughs’ cut-up technique for a new generation of readers. At over 700 pages, however, the novel would have benefited from some judicious editing, and the overall impression is one of a writer too enamoured with typographical tricks. Nonetheless, House Of Leaves is an original and unique novel; for all its faults, it’s unlike anything else you’ll read this year.