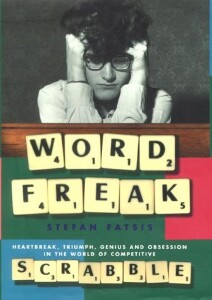

Jonathan Kiefer discusses the torrid world of competitive Scrabble playing with Word Freak author Stefan Fatsis

Sure, Stefan Fatsis is nice, but he’s also a freak. That is, a passionate aficionado – and an unusual specimen. Fatsis is a Scrabble expert. He has written a book about the game, and can speak authoritatively on its mechanics, history, and cultural significance. And he can play, better than most people in the world. But – and this is important – although his Scrabble skill is orders of magnitude greater than yours or mine may ever be, Fatsis is not likely to use the phrase “orders of magnitude,” in conversation or in print, without quotation marks. Nor to use words like “azido” and “oiticica” and certainly not “vogie,” because he understands that such words really aren’t usable, not even on standardized tests. In Scrabble, however, they’re gold.

“You can argue that the process of getting good at Scrabble is the most inclusive use of language,” the clean-cut and bespectacled Fatsis said recently, enjoying the down time between a Reno, Nevada Scrabble tournament and a Berkeley, California bookstore appearance. “You’re using words that don’t get used. I love that!” Thus is Fatsis precisely the appropriate narrator for Word Freak: Heartbreak, Triumph, Genius and Obsession in the World of Competitive Scrabble Players. He is also, of course, the main character.

“It is sort of like Plimpton,” he offered, meaning George Plimpton, the journalist-cum-temporary, tongue-in-cheek Detroit Lions quarterback. “Except I got good.”

Do not think it was easy for Fatsis, normally a mild-mannered Wall Street Journal sportswriter, to become a Scrabble expert, especially in a mere couple of years, and especially while committed to writing a book about trying to become a Scrabble expert in a mere couple of years. He devotes many pages to self-flagellation for a stubbornly intermediate ability.

“The hard part about it was wanting the narrative to turn out a certain way,” he said. “It did add to the pressure. I was fortunate that I was able to get good enough. Maybe it would have turned out differently otherwise.” After a moment, he added, “Or maybe I would have kept playing until I made it.”

As you might deduce, Word Freak keeps its subtitle’s promise, and the gravitational constant in Scrabble’s universe is obsession. But, as Fatsis explains in the text, “I don’t consider Scrabble an obsession in a clinical sense: a disturbing preoccupation with an unreasonable idea.I think of it as an obsession in the colloquial sense, a compelling motivation.” In any case, what writer doesn’t hope for the paid encouragement of his obsessions?

Now, in the interests of propriety, an undertaking of this sort must be considered a battle between the myopia of deep immersion and the insight of distanced perspective; Fatsis, admittedly unaccustomed to first person narration, deftly straddled that tension throughout his book.

“I’m a pretty standard-issue, mainstream newspaper reporter,” he said. “The participatory thing always struck me as a little bit of a conceit.” Fatsis described his first book, Wild and Outside: How a Renegade Minor League Revived the Spirit of Baseball in America’s Heartland, as a more traditional example of “fly-on-the-wall” reporting. He considered it dishonest to try that in Word Freak.

“The deeper I got into this,” he explained, “the more it became about how I felt.” Fatsis wouldn’t like it if people consider Word Freak a memoir. It’s not, but here’s as close as he comes: “When I was nine, in 1972, I calculated how old I would turn in 2000 but couldn’t fathom that day arriving; it might not have seemed so terrifying had I known I’d be playing a board game full-time.” This disarming tone also happens to suit the author’s very thorough reporting, from the “Horatio Alger story” of Scrabble’s inventor, Alfred Butts, to the fascinating variety of mnemonic systems by which the best players have used Butts’ creation as a laboratory for their mad science.

So, were Fatsis to recuse himself, the book would lose a trustworthy guiding voice, not to mention a natural narrative throughline; its minutiae would become overwhelming, even boring; the subculture would seem not to contain universal elements but instead appear more rarified than before; and the whole enterprise might start to feel like a titanic William Safire essay, which, though enlightening, has begun to consume too much of an otherwise useful Sunday.

Instead, Word Freak reads like an anticipated letter from a sharp and funny friend, one who takes the question “What’s new?” quite seriously, and always has a good and true answer. Really, what more should we expect from good nonfiction?

Fatsis is as he seems in the book: disposed to enthusiasm (“I played UNILOBED!” he once interjected, recalling the Reno tournament), or, to put it another way, an especially sporting fellow. He even appreciates the aesthetics of Scrabble, wherein lies a kind of abstract expressionism – the non sequiturs, the shapes of words themselves, the improbable consonance of consonants. Could the meanings of “crwth” or “exergue” possibly be any more useful or satisfying than their sheer, weird beauty? I don’t think so. Look them up.

Actually, Fatsis has staged a relative coup, winning the approval of his chosen subculture twice–first as a participant, then as a journalist. He has befriended the “characters, in both senses of the word,” with whom he traded tolerance, curiosity, annoyance, affection, and absurdly high-scoring Scrabble games. “They’ve read the book by now, and responded well,” Fatsis said. “One character was way weirder than I thought,” one friend told him. “You.”

“It’s not leaving my system,” he said. “I’m not planning to drop out.” Fatsis was referring to the way Scrabble has changed his life. He seemed less concerned with the way his life, a small portion of which is copiously documented in Word Freak, may have changed Scrabble.

“I didn’t write it so that people would play more Scrabble,” he said. “I thought I had a good story to tell. If people start playing more games of the mind.” he shrugged, half-bashfully. “I’d be honoured with that sort of legacy.”