Stephen Mitchelmore finds Thomas Bernhard to be elusive within two studies of the Austrian writer

What if everything we can be depends on playing a role? Where would that leave us? Well, first of all, it would mean that the public self, the one presented to the world, is not “a mask” but the original; the thing itself. Behind the scenes, alone, we live the mystery of self-consciousness. We wonder who it is that wakes at four to soundless dark. Alone, we dream of another life; the one in the biography. Perhaps the oppressive climate of our culture – as seen in the triumphant exposés of the press and the prurience of Reality TV – is due to our frantic need to remove in others what we see as a façade in ourselves. And as art is seen as an adjunct of this removal (“expressing the inner self”), so the inevitable disappointment in its resistant playfulness leads to a shift in preference to revelatory biography and memoir. Could this be stage fright on our part?

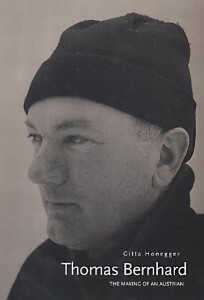

Early on in Thomas Bernhard: the making of an Austrian, the first English biography of the Austrian novelist, playwright and poet, Gitta Honegger says the apparatus of the theatre is an “annoyingly overused existential paradigm”, and she’s right. I’ve only used it once and it’s annoying me already. However, it is clear that her subject is the paradigm’s essential figure. There seems to be no private Thomas Bernhard. As such, Honegger says he is a particularly Austrian phenomenon. The nation, she says, transplanted the baroque theatrics of the old Hapsburg Empire into its cultural life, notably the Salzburg Festival, the state run Burgtheatre, and one man: Thomas Bernhard. Each provided an arena for Austria to conjure its self image.

In Bernhard’s case, it was invariably a negative image, as if Austria needed an impression of embattlement against a hostile world. For example, when Bernhard received a state prize and made critical remarks about the state in his acceptance speech, a Government minister stormed out and slammed a glass door so violently that it smashed. And just before his death in 1989, he was verbally attacked by the President (an ex-Nazi), and physically attacked on a bus by an old lady wielding an umbrella. Since his death, however, Bernhard has become a national treasure. His vitriol has been rebranded, Guy Fawkes-like, into a fireworks display. As a result, his description of Austria as a place with more Nazis in 1988 than in 1938 (the cause of the President’s and the old lady’s wrath) is safely consigned to history. Like the “Anschluss” and the President’s SS uniform, it is part of Austria’s rich cultural heritage. Perhaps this is why, in his will, Bernhard refused to allow the publication or performance of his work within the Austrian state for the duration of the copyright; he foresaw his place in the state circus. (The lawyers have since got around this.)

However, the important thing to remember is that it wasn’t Bernhard who said Austria was still full of Nazis, it was a character in his play “Heldenplatz”. And while everyone assumes Bernhard meant every word as his own, those words are part of a whole that, as JJ Long explains in his book The Novels Of Thomas Bernhard: form and its function, demands to be experienced not in isolation as preferred by the culture-vultures, but in real time. If this is done, irony leaks into the hyperbole and all attitudes become unstable, even irony. In effect, even after death, Bernhard still performs, refusing to become a museum piece. The man himself remains a mystery. So what, in fact, did Thomas Bernhard think? Who was he when alone, no longer dancing before the appalled Viennese bourgeoisie? These are questions for a biography.

But don’t get your hopes up. As Honegger’s subtitle indicates, there is a plea of mitigation. She says her book is a “cultural biography”; as much about Austria as about Bernhard. While this is disappointing, it is also understandable. Most correspondence is unavailable, and friends do not say anything particularly intimate. In fact, the one clear sexual revelation doesn’t alter the image of a performer: Bernhard liked to masturbate in front of a mirror! We’re told this on page 10, so it’s all over pretty quickly. Instead of a chronological narrative, we’re given themes in which Honegger makes frequent (and wearying) digressions into cultural history and their relevance to Bernhard, such as the notion of “Heimat”, and the significance of the theatre in Austria.

In connection with the latter, Honegger rightly makes much of Bernhard’s staging of his experience. In his compelling memoirs (written in five short volumes but collected in English as Gathering Evidence), Bernhard recalls events through the eyes of his younger self while he (the younger self) is also observing or reflecting. He observes his younger self observing from a vantage point separate from the “action”. One observation point leads to another and then another. We might see this as a prime example of Chinese-box Postmodernism where all facts are as hollow as the next, but in Bernhard’s memoir the gnawing question of origin is always there. The facts are plain: Bernhard’s father abandoned his mother before Thomas was born, and died during the war years in mysterious circumstances; he either killed himself or was murdered. He never met his son. Bernhard was later punished by his bitter mother who saw her humiliation in the inherited features of her boy. No amount of virtuoso storytelling and opinionating could prevent the author from being thrown toward the bitter facts of his birth, and its consequences, much as we wonder, whilst vomiting, what we had eaten to cause it.

Bernhard’s early life was also blighted by the Nazi era. He saw at first hand the terror of Allied bombing raids on Salzburg. Barely a teenager, death closed in from all sides. And after the war, when he tried to make his way in the world as a trained singer, he was struck down with tuberculosis after working in freezing conditions in a grocery store. In hospital, with his lungs full of breathtaking sputum, he was given the Last Rites. Miraculously, he survived when all around were dying. Honegger says he wrote the memoir as a record of his victory over that death and the attempts at metaphorical suffocation by his upbringing in particular, and Austrian society in general. Victory was the result of a decision to become himself, to live despite all that suffocated him, even though it was futile. I say “futile” because all that suffocated him also provided the oxygen. It is no coincidence that, despite the oppressive details, there is a sense of freedom pulsing out of the pages of Gathering Evidence. Later, the existential energy of Bernhard’s neurasthenic narrators will also emerge from this outrageous, paradoxical act of will.

Perhaps it because Bernhard provides the most useful guide to his life that Honegger does not attempt to take us through the minutiae of his daily existence. Yet while the analysis is very interesting, one longs for that minutiae. Recently, a BBC Radio 3 documentary on Bernhard revealed that his record collection consisted almost entirely of the 19th Century Romantic repertoire. One might have assumed this great Modernist would have preferred Schönberg and Webern, Bach and Haydn over Schubert and Brahms. Apparently not. (Curiously, this is similar to Beckett). I don’t recall Honegger mentioning anything like this. Nor does she mention the novel Bernhard had sketched out before his death. She prefers to skim over the surface, taking what is necessary for her themed coverage. When it comes to Bernhard’s sexuality, for example, there is an exhausting bout of Freudian analysis arising from his father’s absence and his mother’s maltreatment. It is unconvincing only because it is so persuasive. Actually the same is true of the opinions expressed by Bernhard’s narrators. Perhaps Honegger is having a laugh as our brows sweat over the complexities of Oedipal anxiety? I would like to think so. In the rest of the book, Freud gets barely a mention. It is very odd.

It is also vague. We don’t get a definitive answer as to whether Bernhard was hetero-, bi- or homosexual. Honegger says he “came between couples”, which suggests one conclusion, but what she means is that both sexes were drawn into an ambiguous relationship with the writer. It’s a living example of Bernhard’s elusiveness, and proof of nothing else. Another is the one major relationship outside his family. It was with a woman 39 years older than himself. She was a widow who befriended Bernhard when he was a young writer. She provided a home and material support when he was struggling. He called her his “Lebensmench” (Lifeperson); a word he invented. Understandably, Honegger doesn’t have much to give us on the details of this partnership. All windows are opaque. The same is true, more or less, for other areas of his life. Indeed, Bernhard is a phantom in his own biography.

JJ Long takes a firmer route by concentrating on the novels. Bernhard, he says, was “a writer of considerable diversity, profoundly concerned with the problems and potential of storytelling.” Originally a doctoral thesis, The Novels of Thomas Bernhard: form and its function uses the technical language of Narrative Theory to understand the unique qualities of Bernhard’s writing. Reading it requires a high level of patience and concentration. Moreover, it leaves the lengthy quotations in German untranslated. This is regrettable as those most likely to be drawn to the book – Germanless Bernhard fans – will be hampered. Presumably the costs involved are prohibitive. Still, even monolinguists can gain a good deal from what’s left. Whereas Honegger bizarrely accuses Bernhard of being a solipsist – someone for whom the world is merely a projection of their own mind – Long stresses the “narrative strategies” and “hermeneutic sequences” employed to undermine such narrow interpretations of Bernhard’s monological prose.

For example, he writes that the reflective form of the great, valedictory novel Extinction allows “an excavation of the past even as it moves forward into the future.” The novel’s narrator fires at familiar targets – particularly the repression of the Nazi past – even as he himself succumbs to the same temptation to repress the facts of his own life in order to resist the impending extinction of the title. Indeed, the targets are not only familiar but familial. Long shows how most of Bernhard’s novels – like his memoir – are concerned with “transgenerational transmission” (that is, inheritance). The narrator’s family consists of ex-Nazi parents, both sad and monstrous people, whom he loves and hates in equal measure, as well as grotesque siblings who have not resisted the legacy of repression. As the eldest, the narrator inherits the family’s country estate in darkest Austria when the parents are killed in a car crash. As he also feels that he has not got long to live, he decides he must return from his sunny life in Rome to redeem the legacy. We don’t get to find out how he does this until the final page. As he goes forward to do this, he reflects on why it is required.

Yet the reason why the narrator’s predicament compels our attention, and gives us pleasure, is his spirited unwillingness to complete the task. He is forever delaying the end in both the action as described (stalling outside the gates of the estate) and in the act of storytelling itself (spinning variations of anecdotes and opinions). Long says these delaying tactics are achieved through “embedded narratives” and “retarding elements”. As a successful doctoral candidate, “pleasure” is not an issue for him, but for those of us who turn to Bernhard for this reason, it is interesting to note how these techniques create an experience similar to the reading of a thriller or detective novel. In those genres, pleasure comes from the growth of mystery and suspense before the inevitable denouement.

Extinction is similar in that one reads to find out what happens next. However, the distinction is that the thriller cannot reproduce the same pleasure on re-reading. A new story is required every time. Extinction on the other hand positively demands to be re-read in order to enjoy that delay again and again. In fact it becomes more enjoyable as we join with the narrator repeating stories and opinions in order to delay our return to the mundane world. Unfortunately for him, the delay has more serious import for the narrator. For a time, we feel more alive even if our noses are “buried in a book”. This is the great problem and potential of storytelling. Long’s analysis, which is richer and more complex than I have space (or patience) to detail, manages to elucidate Bernhard’s method and highlight his remarkable technical achievement. One cannot go away from this book and still believe, as so many do, that Bernhard is merely a ranting egoist. Those who already know better will perhaps understand more clearly how Bernhard maintained his high-wire act, though we would still like to know more in physical detail.

In one brief insight to his working process, Honegger quotes Bernhard as saying he wrote “with full commitment”; his entire body took part in the creative process. Perhaps this is why he preferred to call his novels “prose texts” as this suggests a script for performance. Indeed, Bernhard’s many plays are not greatly different from the novels. It seems Bernhard himself felt most alive when writing, like an actor on stage even at his writing desk. Honegger observes that each work was a reassertion of that early decision to live. Appropriately, some way into Extinction, the narrator reflects on the frustrated lives of those stuck in small-town provincial misery from which he, the narrator, had escaped. He says they fail to better themselves, to “get away from their real selves” because

“they lack the intellectual energy, because they have not discovered the intellect – the intellect around them or the intellect within them – and have therefore not taken the first step, which is the precondition for taking the second.”

So, we might assume that in writing, Bernhard got away from his real self. But “full commitment” means he did it with his mortal body as well as his intellect. Despite his early escape from death, Bernhard was always seriously ill. He expected to die before reaching fifty. His half-brother, a doctor, claims to have kept him alive for an extra ten years after that. Mortality was an over-riding theme and writing was at once the escape from death’s imminence and its enactment. Barthes’ Death of the Author was more than a concept to Bernhard. In fact, in a blessed piece of minutiae, Honegger tells us one of his favourite games was “playing dead”. It’s a nice idea to think of the novels as the place were Bernhard plays dead for us. Nowhere else is he more alive.