Gary Marshall

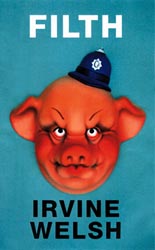

When Trainspotting rapidly grew from underground publishing success story to zeitgeist-surfing, underworld-soundtracked cultural event, Irvine Welsh was described as a spokesman for a generation and the most exciting writer in Scotland. While the use of language and setting was something of a novelty first time round, Filth is Welsh’s fifth novel and revisits the same ground as everything else he’s ever written. We have deviant sex from The Acid House, Tarantinoesque musings on rock records from Trainspotting, half-arsed attempts at psychology and social comment from Marabou Stork Nightmares and, of course, lots of swearing. As with most recent Welsh product, it’s also a shambolic and incoherent mess.

Filth tells the story of Bruce Robertson, an Edinburgh policeman whose life resembles Harvey Keitel’s in Bad Lieutenant. Racist, misogynist, homophobic and psychotic, Robertson devours hard-core pornography whilst mentally and physically abusing himself and everybody around him. Despite his appalling personal hygiene supplemented by a genital rash and an attack of tapeworms (more of this later), he nonetheless manages to have sex with almost every female he meets, in between setting up colleagues for queer-bashing or driving others to the brink of suicide.

Robertson isn’t really a bad person, though. As his tapeworm explains in the latter chapters of the book – yes, the narrator is quite literally talking out of his arse – Robertson has had a tough time. He came into the world as the result of a violent rape, his adoptive stepfather made him eat coal, and the first love of his life died. The section describing the death of his first girlfriend is the only funny part of the book as Welsh goes massively over the top, piling on the pathos as he recounts how the poor crippled girl is struck by lightning in a scene that could have come straight out of an Airplane movie. Unfortunately this bit is supposed to be serious.

The book runs to about 400 pages and fully 300 of them repeat the same endless catalogue of sex, violence and hatred with little in the way of variation. Some of the scenes are evidently supposed to be funny, such as the set-piece where Robertson attempts to make a video of a prostitute being penetrated by a dog or when he sleeps with a colleague’s wife after framing her husband for making obscene phone calls. Conspicuous by their absence are the wit and invention that characterised Welsh’s earlier novels, like the foul-mouthed baby in The Acid House or Sick Boy and Spud in Trainspotting. Weighed down by the expectations of his audience, Welsh has produced a book that fails on every single level: a comedy that isn’t funny, a police procedural that can’t be bothered with the details, a tale of redemption without any trace of warmth or sympathy for any of the characters and a closing plot twist that’s visible from the first chapter.

There’s a tradition in reviewing where you make sure you don’t give away the ending of a novel for fear it will prevent people from reading it. Hopefully, then, the news that Robertson committed the brutal murder he’s supposed to be investigating throughout the book and then kills himself at the end should prevent people from wasting their hard-earned cash on this pathetic attempt at a thriller. Maybe then Welsh will stop recycling past novels and will attempt to write something that’s actually worth reading. To describe Welsh as the greatest writer in Scotland is a huge insult to talented writers such as Jeff Torrington, William McIlvanney, James Kelman, Iain Banks and Janice Galloway who produce novels which combine well-drawn characters with empathy and social conscience.

Although the title works on several levels – Filth as slang for policemen, or as a description of the world in which Bruce Robertson lives – the publisher was too restrained. A more fitting title for this shambolic, scatalogical mess of a book would have been Shite.