Chris Mitchell

When world chess champion Garry Kasparov was defeated by IBM’s Deep Blue II last year, it provoked a renewed popular interest in the possibilities of artificial intelligence. Kasparov commented that he felt he was playing “an alien intelligence”. But was Deep Blue really thinking or simply number-crunching at a incredible speed to produce the illusion of thought? It’s a question which goes back to the very inception of artificial intelligence and which John L. Casti tackles through the medium of what he terms “scientific fiction”.

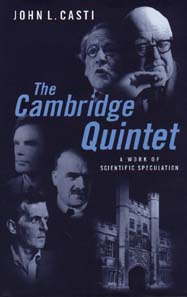

Instead of providing a factual overview of the last half-century’s experiments with thinking machines, Casti convenes a fictional meeting of minds in the Cambridge rooms of novelist, civil servant and physicist C. P. Snow. By bringing together Alan Turing, who pioneered the idea of a machine being able to replicate human thought processes, with the language philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein and the quantum physicist Erwin Schrödinger, Casti gathers the whole spectrum of opinion about the possibility of artificial intelligence under one roof. Making up the quintet is the geneticist J.B.S. Haldane. The eclecticism of the quintet’s interests indicate the complexity of artificial intelligence, which is as equally bound up with philosophy as it is with science.

While Casti’s prose won’t gain him any nominations for the Booker Prize, its brevity makes light work of those complexities without oversimplifying them. The debate is mainly centred around Turing’s advocation of the human brain as nothing more than a complex computer which can be replicated, and Wittgenstein’s insistence that human thought and language cannot be understood by anything that is non-human, precisely because it is not part of the human world. “If a lion could speak, we would not understand him”, as he famously but enigmatically put it. The other three members of the quintet largely referee and play devil’s advocate to the two protagonists.

It wasn’t until 1956, several years after Wittgenstein’s death and Turing’s suicide, that artificial intelligence was formally inaugurated as a discipline. By getting back to the roots of artificial intelligence’s inception, Casti crystallises AI’s essential arguments in an easily accessible form. His afterword provides a breakneak tour of AI’s subsequent developments since the quintet’s fictional meeting in 1949, up to Kasparov’s defeat.

Deep Blue II seems to have fulfilled Turing’s belief that a machine can exhibit intelligence by its external actions, but how it arrives at those actions seems to have little to do with actually replicating human intelligence, as Casti notes. Perhaps Wittgenstein was right – that artificial intelligence cannot have any reference to human intelligence and that it is indeed, as Kasparov said, “alien”. Either way, it looks like we have a long way to go before Bladerunner becomes true.