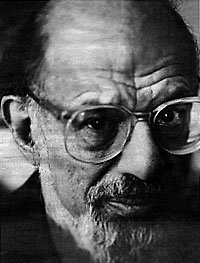

Graham Duff meets Allen Ginsberg, the self styled “old auntie of the Beat Generation”

Allen Ginsberg – poet, Jew, Buddhist and self styled “old auntie of the Beat Generation” – is 68 years of age. Forty years on from the publication of Ginsberg’s infamous Howl, his latest collection, Cosmopolitan Greetings: Writings from 1986-92, has just hit the bookshelves. Sipping tea and talking about his greatest influences William Blake, Walt Whitman, William Carlos Williams and Jack Kerouac, Ginsberg is friendly, assured and (naturally enough) beatific. But perhaps surprisingly, he’s almost as at ease talking about Sonic Youth and Gavin Friday as he is fellow beats William Burroughs and Gary Snyder.

With lyrical incantations, dream notations. calypso rhythms and haiku, Cosmopolitan Greetings shows a writer moving in ever increasing circles, the subject matter ranging from the intensely personal to the passionately political. I ask if it’s difficult writing under the weight of his past work.

“My mind is much too fragmented for the solidification of any single thought like that. Consciousness itself is discontinuous I think. As a Buddhist, that’s my take on it. Shakespeare at the end of The Tempest has Prospero say ‘Thence to Genoa where every third thought shall be my grave’. So every 244th thought: ‘Oh I’m Allen Ginsberg and I have a history.’ The rest of the time [it’s] ‘there’s the tea, I got to go to the bathroom, how’s my diabetes? What’s this guy saying to me?’ So yes, there is the information of being around for 40 years writing poetry and knowing a lot of people but then every moment is completely blank and new.”

Despite an enormous body of work which bristles with positivity, passion and affirmation, Ginsberg admits, “I got the reputation of being this negative nay-saying rebel. I don’t know why. But maybe the purpose is starting to come through now after all these years. People are beginning to read without the intervention of the media saying ‘these angry, wrathful, idiot people smoking dope in dirty flats covered in flies’. That was the official party line of the media back in the early Sixties.”

At this point Ginsberg goes off to take a phone call which turns out to be from Salman Rushdie. ‘I saw him when he came to New York. We did some meditation classes together -’cause he’s got lots of time.”

In recent poems such as Sphincter and After Lalon, Ginsberg details the ageing process with undiluted candour whilst in his more directly political poems he is still on a mission to report the unreported.

“I’ve always been preoccupied with the intersection of repressive dope laws, dope dealing by French intelligence and American CIA, the expansion of killer drugs like tobacco and alcohol and political manipulation by cigarette and alcohol interests, the corruption ot govemments, police departments and so on. We are ruled by fantastic hypocrisy.

“In America the theo-political right – the FCC and Jesse Helms – has seized control of the main market place of ideas: radio and television. So we don’t have a free market in ideas now. So the censorship that normally applied to books and print and film is now being applied to the electronic media and may be applied to Internet before it’s all over. My own poetry has literally been ripped off the air during the day. My poems are studied in high schools and colleges, but in October 1988, Senator Helms – who is subsidised by huge tobacco interests – rushed through a law signed by Reagan which affectively means that ‘obscene language’ can only be broadcast between the hours of midnight and six am. This being to protect school kids who are reading my poems in class anyway.”

A vivid conversationalist, the elder statesman of the counter culture is at his most animated when recalling the routines he used to improvise in his apartment with Burroughs and Kerouac in the 1950s.

“After dinner, drinking coffee, smoking grass, we’d act this stuff out. We all had ditferent characteristic roles: the well groomed Hungarian – that was me. The naive American in Paris with a straw hat – Kerouac. Bill dressed up as a shifty vicious governess. Bill would end up creased up laughing on the floor. I think the key to the Beat Generation was spiritual liberation. Then media liberation of the word; the battle with censorship, sexual liberation. It ricochets out, but it started with a spiritual liberation. I always thought that Howl was a very exuberant and positive and funny poem. But at the time it was taken to be the ravings of this angry, rebellious jerk.” These days things are a little different. “I’ve got a really good job. It’s called Distinguished Professor of English, which means I only have to go in one day a week.”