Gary Marshall

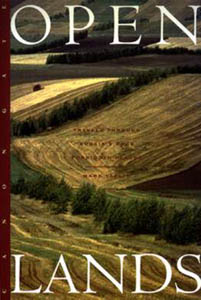

During the Cold War huge areas of Russia were strictly off-limits to foreign visitors and, in classic tit-for-tat style, Russian visitors were allowed entry to the USA provided their travels didn’t take them anywhere there were roads, people or small animals. In 1992 both superpowers signed the “Open Lands” agreement (from which Mark Taplin’s book takes its title), abolishing travel restrictions and allowing visitors into areas which had not seen foreign faces for decades.

At first glance Open Lands is travel writing, a straightforward account of Taplin’s travels throughout previously forbidden towns and districts. The book, however, also provides an insight into the turbulent history of Russia and encompasses both humour and poignancy. Like the very best travel writing this is no mere account of sights seen and locations visited – more than just a travelogue, Open Lands is also a complex and powerful social history.

Taplin’s travels include the railways which served the infamous Gulags, and the sections of the book where he describes the treatment of prisoners and the justified paranoia of the intelligentsia is particularly moving. He quotes a letter sent to an adolescent girl by her father: “I have only just found out that you are an enemy of the people, one of those who interferes, stands in the way. I can’t forgive myself that I didn’t detect this during your childhood. After everything that has become known to me, you cannot count on letters, nor support from my side”. The promising student hung herself the following day.

As his journey progresses we discover photographs of churches long since razed to the ground by revolutionaries and listen to tales of academics harassed and discredited, well-meaning modernist politicians defeated by vote-rigging, corruption and intimidation. Taplin presents a picture of a proud people trying to make sense of a complex situation. “Like an amnesiac awaking from a blunt-force trauma, Russia longs to understand what it once was and what it might have been – the first step towards restoring its true identity… for Russians, what constitutes civilisation remains the enigma. Where did we go wrong? How do we return to normalnaya zhizn, normal life?”

Although he pulls no punches when describing the corruption which besets Russia even in the present day or the horrific abuses of power prevalent throughout the Party era, Taplin is equally at home recounting tales of Jazz festivals or terrifying journeys with maniacal Thatcherite entrepreneurs. He has a keen eye for the absurdities of life in modern-day Russia, too, a world where it is “easier to buy Tom Clancy than Chekhov” and Korean restaurants refuse to serve Korean food.

Despite the scale of the undertaking and the sheer amount of information packed into each page, Taplin’s conversational writing style ensures that the pace doesn’t flag for a moment. As Taplin himself notes, “a fair amount of my information came from random conversations in planes, trains, cars and buses – the past recounted, if you will, from the perspective of a third class coach”. Rather than the dry, academic tome which you feel Taplin believes he should have written, Open Lands is a vivid and lively account of a country trying to find its role in a changed world.